Contingency and the Cartographic Making of New England (Part I)

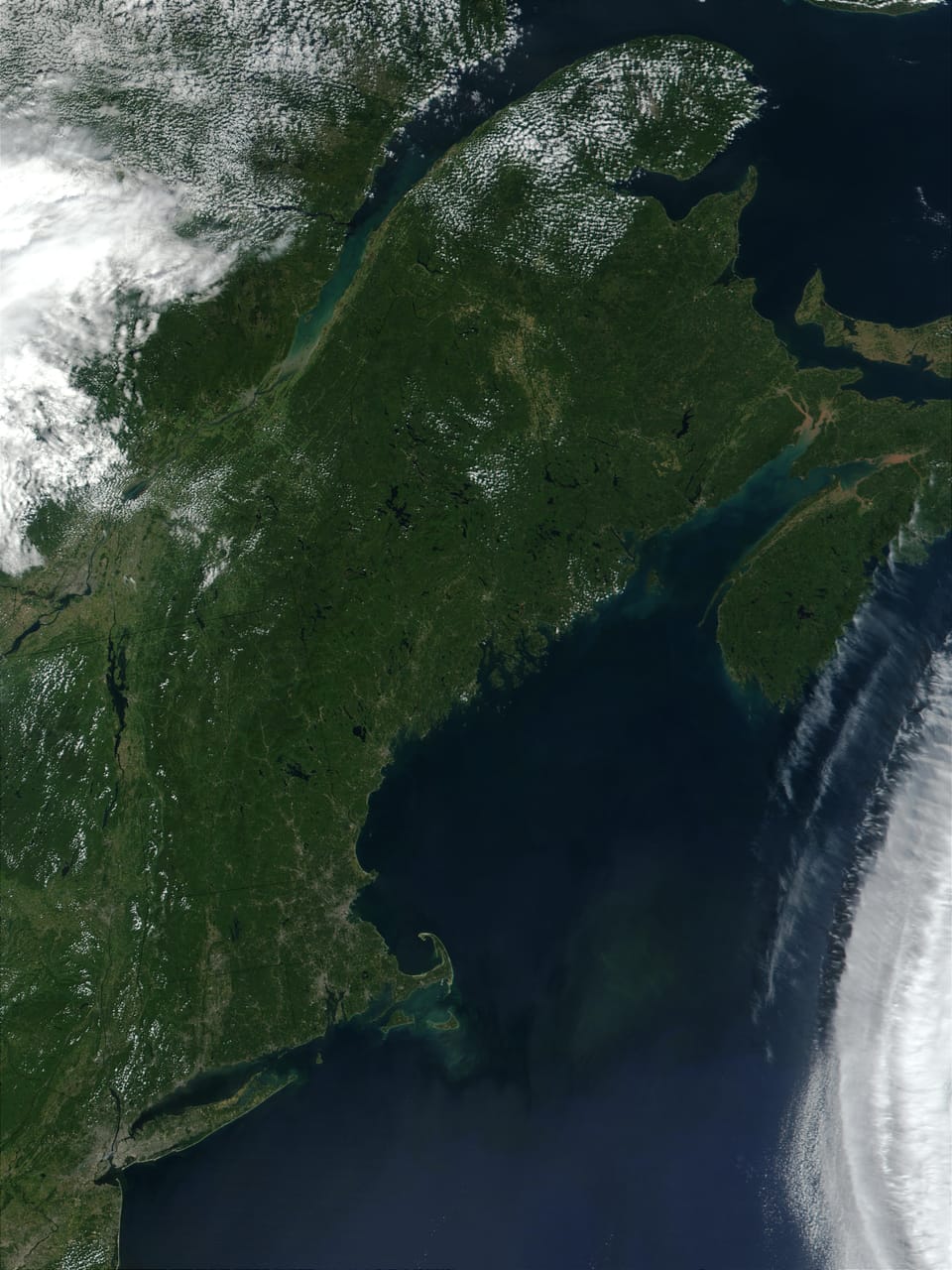

If you trace the East Coast of the United States north from Florida on a map, you'll encounter two significant detours from the prevailing north-south orientation of the coastline. The first is a long northeastward stretch that starts at the Florida-Georgia border and continues to the Outer Banks of North Carolina and Cape Hatteras, before returning more or less due north. The second is more abrupt: at New York Harbor, the coast makes a nearly ninety-degree turn to due east. This turn marks the southwestern boundary of New England, which juts eastward along the Connecticut and Rhode Island coasts to Cape Cod. After a brief northward stretch along Massachusetts Bay, the coast turns northeast again at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, continuing to the furthest reaches of Downeast Maine.

This abrupt and lengthy jog to the east makes New England a peninsula of sorts and accounts for its weather, which is generally wetter and more variable than New York's—not because New York is so much to the south, as the highway signs suggest, but because it's to the west. The boundary between New York and the New England peninsula is defined by the north-south course of the Hudson River and the steep cliffs of the Palisades, twenty-odd miles west of Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Vermont.

These features—the abrupt eastern jog at Long Island Sound and the natural boundaries of the Atlantic Ocean to the east and deep gash of the Hudson River to the west—make New England's borders seem somehow natural, perhaps like Great Britain, which is fully separated from continental Europe, or India, which is isolated from the rest of Asia by the Himalayas.

But look to the northern borders of New England, and it's clear the lines were not set by nature. The natural boundary with Canada would seem to be the St. Lawrence River, as it is in upstate New York. But in far northeastern New York, the Canadian border leaves the northeastern course of the St. Lawrence and makes an unnatural bolt due east along the top of Lake Champlain, across the tops of Vermont and New Hampshire to the Connecticut Lakes and the headwaters of the Connecticut River. There it begins a crooked path to the northeast, roughly parallel to Quebec's Notre Dame Mountains, before turning abruptly south, roughly parallel to New Brunswick's St. John River, to meet the Gulf of Maine at Calais.

This chaotic squiggle of a northern border betrays the fact that New England's boundaries are anything but natural. To look closely at a map of New England is to see a landscape defined not by physical geography, but by historical contingency. Our borders are the physical residue of missed connections, suppressed data, and the sheer randomness of 17th- and 18th-century surveying. The "notches" and "necks" we see today are the fossilized remains of four centuries of accidents, errors, and negotiations.

Had a single surveyor's compass been better calibrated, or a single royal decree arrived faster, the region we call "New England" might have included all of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia; or formed just the southernmost tip of Canada; or have been a fragmented collection of much smaller fiefdoms. To understand the New England that is, we must look at the moments where the data shifted and imagine the alternative New Englands that almost were.

Southern New England

The internal boundaries of Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island were established by 17th-century surveyors, and the lines they drew were only as good as their equipment—which is to say, not very good. What resulted was a patchwork of errors and misunderstandings that had to be negotiated over the next two centuries. Here are a few of those negotiations.

The Southwick Jog

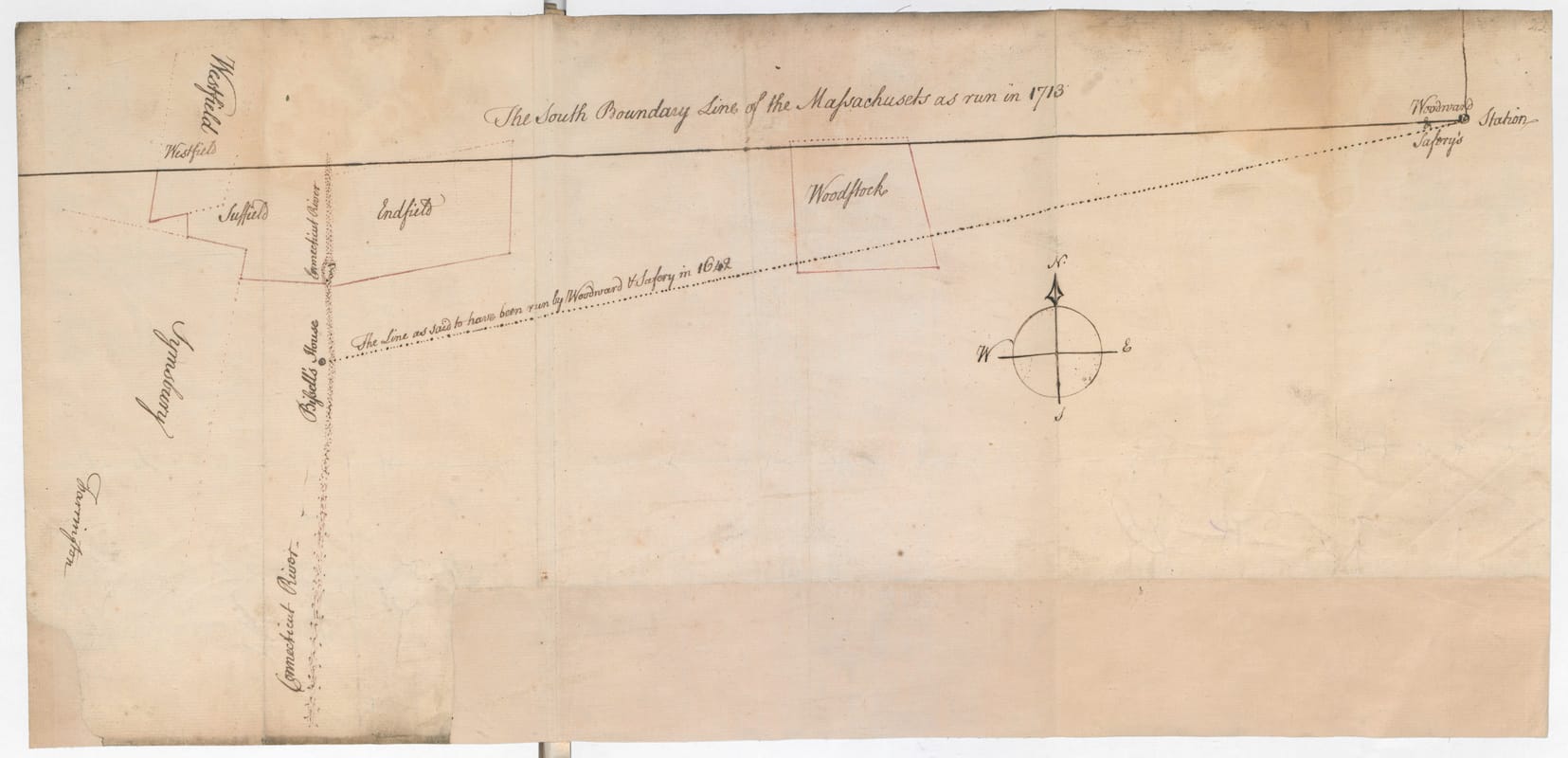

The most famous surveying error in the region is the Southwick Jog, the curious rectangular bite that Massachusetts takes out of north-central Connecticut. Its origins lie in a 1642 survey conducted by Nathaniel Woodward and Solomon Saffery. Tasked by Massachusetts to find the colony's southern boundary (defined as three miles south of the southernmost point of the Charles River), the pair started at the wrong point and allowed their measurements to drift nearly eight miles south as they headed west.

For more than a century, Massachusetts claimed this "stolen" strip of land over Connecticut's objections. While most of the border was eventually straightened in the 18th century through a series of commissions, the residents of Southwick, Massachusetts, refused to be transferred to Connecticut. The 1804 compromise resulted in the "Jog" or "Notch," a permanent cartographical monument to a 17th-century surveying error.

Had Woodward and Saffery been more precise, the line would be clean and horizontal, and the Jog wouldn't exist.

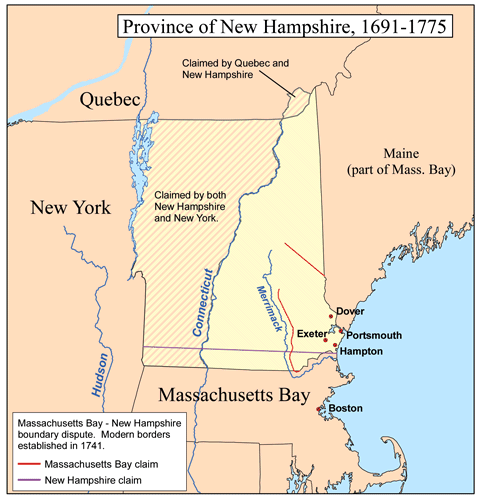

The Merrimack "Bend"

A similar contingency occurred to the north. The Massachusetts charter defined its northern boundary as three miles north of the Merrimack River. However, 17th-century cartographers didn't realize that the Merrimack turns sharply north in central New Hampshire. When they discovered this, Massachusetts interpreted the charter literally, claiming its territory should follow the river's bend all the way to its source at Lake Winnipesaukee.

Had this interpretation held, the entire Merrimack Valley, including Manchester and Concord, would be in Massachusetts. New Hampshire would have been reduced to a tiny coastal buffer state with no industry, no Lakes Region, and no skiing. It took a 1740 Royal Decree from King George II to set the straight east-west line we see today. The king, increasingly frustrated by Massachusetts's growing confidence and territorial ambitions, was not inclined to let the colony expand further.

The Horse's Neck and The Oblong

The boundary between Connecticut and New York was shaped by a different kind of data failure: conflicting "Sea-to-Sea" charters. Connecticut's 1662 charter claimed everything west to the Pacific. New York's 1664 charter claimed everything east to the Connecticut River. Something had to give.

When they negotiated in 1683, they agreed on a "Twenty-Mile Rule." The border would run twenty miles east of the Hudson River. However, Connecticut settlers had already established the towns of Greenwich and Stamford within that twenty-mile zone. To keep these coastal settlements, Connecticut traded away a sixty-mile-long, 1.8-mile-wide strip of land further north, known as The Oblong.

This trade created the "Horse's Neck" panhandle that extends down to Greenwich and ensured that Connecticut held onto what would become its Gold Coast. Had Connecticut's negotiators been less willing to compromise, or had they arrived at the table a few years earlier before those coastal towns were established, the border might have been a clean north-south line, and Greenwich might be in New York.

The Pawcatuck Compromise

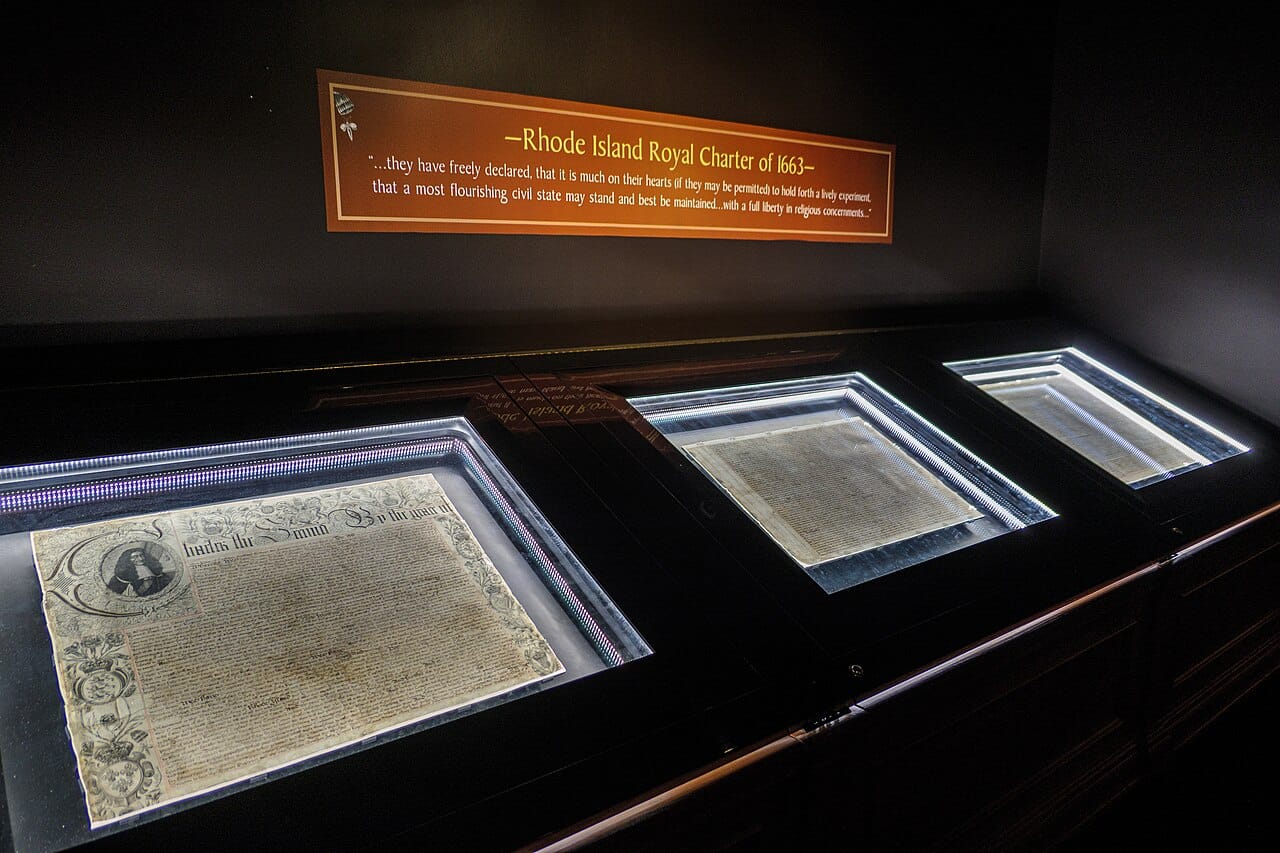

Rhode Island nearly ceased to exist due to a similar charter conflict. Connecticut's 1662 charter claimed everything east to the Narragansett River. Rhode Island's 1663 charter claimed everything west to the Pawcatuck River. The problem was that both charters claimed the same territory—roughly modern-day Washington County, Rhode Island, more than a third of the State.

For eighty years, local farmers faced double taxation from both colonies, paying levies to whichever colonial authority showed up to collect. Had the older Connecticut charter prevailed, Rhode Island would have been reduced to Providence and a few islands in Narragansett Bay, likely making it too small to survive as an independent political entity. It would probably have been absorbed by Massachusetts or Connecticut, and we'd have one fewer state today.

The 1703 compromise that established the Pawcatuck River as the boundary preserved Rhode Island's viability, but just barely. The decision to honor the younger charter over the older one was itself contingent. Had the Crown's commissioners sided differently, Rhode Island might exist only as a historical footnote.

Not Natural

These data errors and document conflicts gave shape to Southern New England, with all its juts and jogs and panhandles. Each irregularity is a fossil of a miscalibrated compass, a misread charter, or a messy negotiation between colonial rivals. The borders we see today feel permanent, natural, even inevitable. But they're none of those things. They're accidents that calcified into facts.

These were merely interstate disputes, relatively easily resolved between neighboring English colonies. In the next post, we'll explore the making of Northern New England's borders and the much more dramatic international stakes that shaped them—stakes that involved not just competing colonial charters but competing empires, and not just surveying errors but wars.

Member discussion