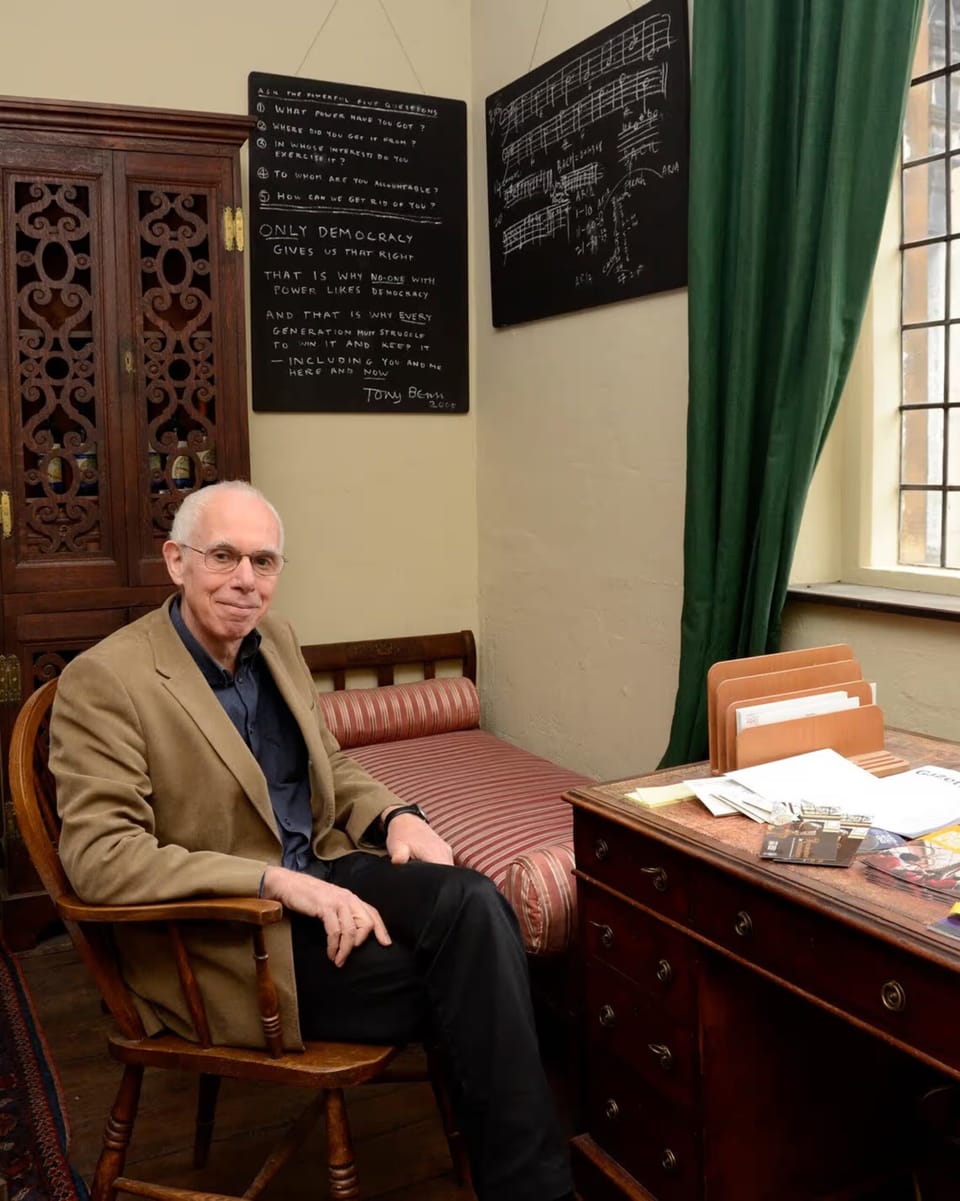

Jim Bennett, Digital Humanist

I've just returned from London, where I joined a celebration at the Science Museum of the life of my D.Phil. thesis advisor, Jim Bennett. Jim was one of the world's foremost experts on scientific instruments, a innovative museum practitioner, an incredible teacher, and a kind and generous friend. After finishing my degree, my professional career took a path that led away from Jim's core interests in the history of mathematical practice in astronomy and navigation and the related history of scientific instruments, but his influence on me was profound and persistant. Here's the tribute, more or less verbatim, that I offered yesterday.

Introduction

Although the term “digital humanities” wasn’t formally minted until 2004, scholars and curators have experimented with digital methods since the dawn of the computer age. Among those early adopters was Jim Bennett. In the mid-1990s, as Keeper of the Museum of the History of Science in Oxford, Jim was among the first scholarly practitioners to see the potential of the World Wide Web for teaching, research, and public engagement. For Jim, the Web combined the intellectual depth of the collections database with the public-facing affordances of the gallery, and he expertly drew upon his experience with both to build groundbreaking digital collections and online exhibitions. This paper explores Jim’s digital practice and legacy, arguing that the habits of mind and professional commitments that defined his career made him a truly pioneering digital humanist—even if he never used that term to describe himself.

In my nearly 25 years in digital humanities, I have come to believe that digital humanities has at least six major characteristics that distinguish it from traditional scholarship. Digital Humanities is:

- technological

- collaborative

- archival

- networked

- public

- practical

This is a framework I have developed over many years to describe my own professional commitments and have passed on to a generation of students. But it was only in reflecting on Jim’s life after his passing that I realized how much my vision of the field was, in fact, modeled on his example. Each of these six characteristics was a hallmark of Jim’s work long before ”digital humanities” even had a name.

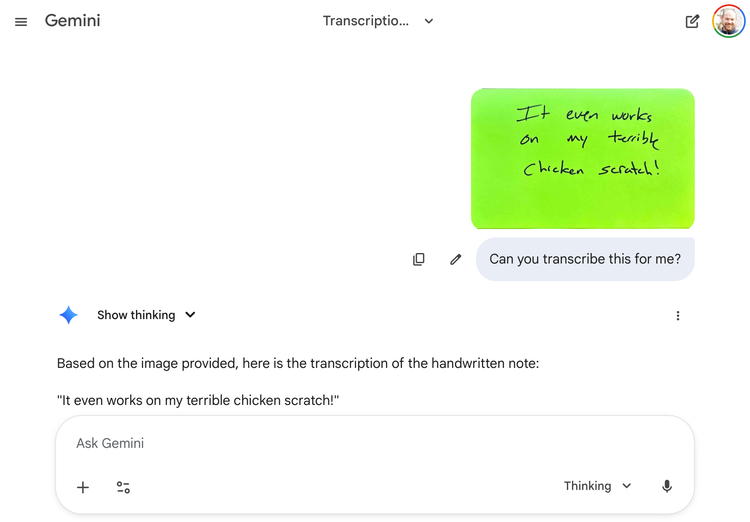

1. The Technological

Most obviously, Jim was a pioneer in bringing the history of science to the World Wide Web. When I arrived in Oxford as a master's student in 1998, and the Web was still in its first decade, Jim and his colleagues at the Museum of the History of Science in Oxford (now the History of Science Museum) had already spent three years developing that institution’s earliest websites. These were not mere advertisements for the physical museum (as were most museum websites of the day) but scholarly works in their own right, among them The Measurers: A Flemish Image of Mathematics in the Sixteenth Century, The Geometry of War, 1500-1750, and The Garden, the Ark, the Tower, the Temple. The choice of subjects for these early experiments was clearly shaped by Jim's deep engagement with the materiality of science. Just as his historical subjects used instruments to make scientific knowledge, Jim intuitively grasped the potential of the Web as the latest instrument for making historical knowledge. It was into this rich culture of technological experimentation that I was thrust, still just a kid.

Coming from an undergraduate program in History and Science at Harvard and my first job in public history at the Colorado History Museum in Denver, it was the public aspects of the Museum’s work and its M.Sc. program that interested me most. However, when I arrived, I found the Museum's galleries closed for a major renovation, a closure that would last for nearly the entirety of my time there. As a substitute for the hands-on curatorial work we would have otherwise performed as docents or exhibition assistants, Jim tasked me and my fellow students with a new kind of practical assignment: building a website. The result of this work was Cosmographia, an exploration of Renaissance cosmography through the Museum's instruments. It was the first website I ever built.

I look at it now, especially at its code, as something of an object of horror. (Although I will note that it still loads, probably more a testament to the dedication of HSM staff and the resilience of HTML 1 rather than anything I should take credit for.) But for me, that project was a tentative first step into a new field that didn't even yet exist. That project would come to define my career, and it was Jim who first introduced me to this "artificial practice."

2. The Collaborative

Digital humanities is distinguished from traditional scholarship less by its tools than by its organization of labor. The traditional model of humanities scholarship is that of the lone scholar whose highest output is the scholarly monograph. The labor of traditional humanities is organized around the spaces of the archive or, less romantically, the department hallway, where individual scholars work in individual offices on individual research projects. Digital humanities, by contrast, is more commonly organized in a center or a lab, an open-plan setting where people with diverse skills work together. Its highest output is the "project," a multi-authored collaboration between some combination of researchers, writers, archivists, designers, developers, and project managers, among many others.

The idea that a project requires a range of expertise rarely held by a single person is now a core tenet of digital humanities, formally encoded in documents like the Collaborators’ Bill of Rights and repeated so often as to be a cliche. But Jim was practicing it long before it was commonplace. The collaborative mode of work came naturally to him, partly because of his grounding in museum exhibitions and partly by instinct. He understood that, like an exhibition, a website is not the product of one person, but of many people working together—an emergent thing made in the making.

This sensibility was also rooted in Jim’s historical sensibility, in his efforts to reveal the importance of the more technical and instrumental aspects of scientific collaboration. It was Jim who first introduced me to Steven Shapin's concept of the "invisible technician" in scientific collaboration—to Wren and Hooke, Boyle and Hooke, Boyle and Papin, Davy and Faraday, Joule and his unnamed brewer colleagues, and all the rest. While the analogy isn't perfect—the power dynamics and labor conditions have certainly changed over the centuries—the fundamental principle (and injustice) of visibility and invisibility in collaborative work remains a potent one. And unlike some of his scientific subjects, Jim was meticulous in his acknowledgement, in making his many collaborators visible. Many of those early digital collaborators are here today, including Stephen Johnston, Scot Mandelbrote, and Silke Ackermann.

3. The Archival

Jim understood that the Web wasn’t just a catalog or a brochure. It was, at its heart, an archival technology. Jim knew that a digital project's character and value stems from the structured data that underpins it. With his colleagues and students, he was an early pioneer in seeing the advantages of the database and moved the Museum’s online work from flat HTML to web-database technologies as soon as coding frameworks and bandwidth constraints made those technologies feasible.

A prime example is Epact: Scientific Instruments of Medieval and Renaissance Europe. Launched in 1997, it was an online catalog of over 600 early scientific instruments and a remarkably early example of web-database technologies in scholarly work. If memory serves, it initially used Microsoft's Active Server Pages (ASP) but was soon rebuilt using the open-source "LAMP stack"—Linux, Apache, MySQL, and PHP—which became the technical foundation for the Web 2.0 era. This demonstrated a profound understanding of how a database could function not just as a finding aid, but as a dynamic tool for research and discovery. Of course, Jim didn't code the site himself, but the fact that he blessed the innovative leap demonstrates the profound trust he placed in his colleagues.

4. The Networked

Epact could not have been created by the Museum of the History of Science alone. From its inception, it was conceived as a networked resource, a partnership between the museum, the Museo di Storia della Scienza in Florence, the Museum Boerhaave in Leiden, and the British Museum. Another example of Jim's network building was his support for the launch of RETE in 1996, a listserv that still underpins the worldwide network of scientific instrument studies.

But Jim's network building was not only external. As the Museum of the History of Science’s Keeper, Jim was the central node of the internal network he built to make this work possible. Jim was an institution builder who fostered a culture of experimentation, secured resources, and hired key staff. He was also the center of a network of students like me who have carried his ideas and methods far and wide. Jim was a leader who created the network conditions for work to happen, building the intellectual, administrative, and educational infrastructure for a new kind of scholarship.

5. The Public

The dominant narrative of the history of digital humanities often begins with the literary and textual punch card analysis of Father Roberto Busa‘s Index Thomisticus in the 1950s and proceeds through the founding of the Text Encoding Initiative in the 1980s and 1990s through to the Large Language Models of today. But an alternative genealogy—one that resonates with many digital historians like myself—begins (in the U.S. at least) with the technology-inflected work of public oral historians and folklorists like Allan Nevins and Alan Lomax in the 1940s. A relatively straight line can be drawn from their oral history and folklife collecting movements to the radical social history of the 1970s to the founding of key digital public history institutions like the American Social History Project/Center for Media and Learning at the City University of New York and the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media at George Mason University, where I went to work in 2002 after leaving Oxford.

This alternative history places digital humanities squarely in the mainstream of public history practice—the very waters in which I have waded since before my time at Oxford. Jim was a committed public historian. His writing and lecturing were famously lucid, but his commitment to public scholarship went well beyond the occasional magazine article or radio appearance. The weight of his output lay in museum exhibitions, where his commitment to a broad public, as opposed to just a narrow band of academic specialists, is most evident. His public history was not that of a "public intellectual" but that of a practitioner in direct engagement with the public, for example in the artist residencies he sponsored at MHS, in the many teaching resources the museum created during his tenure, or by inviting enthusiasts into the museum to explore the science, art, culture, costume, and community of Steampunk. Indeed, this legacy of public co-production of historical knowledge, of "shared authority" in the terminology of public and oral history, thrives at the museum today in its Public & Community Engagement initiatives, such as the Troubling Standards program and the MultakaOxford project. These works of public history fit very neatly into the history and tradition of digital history as I’ve told it and make Jim’s entry into digital humanities an utterly natural one.

6. The Practical

From its earliest days, digital humanities has been animated by a productive tension, often summarized as "hack vs. yack" or sometimes “grok vs. talk”—a debate about whether our field is more about scholarly interpretation or the hands-on building of digital things. I've tended to fall on the building side of this debate. To me, digital humanities is mainly a "methodological commons," a shared commitment to practice rather than a set of intellectual interventions.

But Jim's career has been an ever-present example not to take this argument too far and shows that the "hack vs. yack" debate is a false dichotomy. For Jim, the practical and the intellectual were inseparable. This conviction was born from his dedication to the physical objects of science. Instruments, in his view, weren't just illustrations of ideas; they were active agents in the making of knowledge. This was the great insight of his historical scholarship: in the idea of "practical mathematics," Jim showed that scientific knowledge came not just from thinking and writing, but from making, measuring, and building, and that the two were mutually reinforcing and indispensable. This insight applies equally to astrolabes and iPhones.

Conclusion

As the title of today’s conference attests, Jim’s curatorial and digital work was a direct extension of this synthesis of ideas and things. As Stephen Johnston has noted, Jim self-consciously called himself "a museum practitioner.” I have adopted this formulation, often calling myself a "digital humanities practitioner."

For me, as it was for Jim, the digital is an instrument for knowing the past. I have carried the lessons he taught me through my quarter-century in the field, and it just now occurs to me that I have become an instrument maker. His model of technologically inflected, collaborative, practical knowledge-making is a legacy reflected in the institutions, the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media at George Mason and Greenhouse Studios at the University of Connecticut, that I have helped build in the United States. We rightly celebrate Jim Bennett’s life as a historian of science. I'm here to add to it a celebration of Jim as a digital humanist.

Member discussion