The Measles Crisis Is Regional—Let's Keep It That Way

You may have seen news that the United States is at risk of losing its measles elimination status from the Pan American Health Organization based on a surge in measles cases that has occurred over the past two years. You may have heard stories, for example, about South Carolina's current outbreak or the one that hit Texas last spring and summer. This is surely a national story, as we now have an anti-vaxxer leading the Department of Health and Human Services (and, by extension, the Centers for Disease Control) in RFK, Jr. The pandemic, moreover, should have taught us all that viruses know no borders.

But that does not necessarily mean that measles is currently a national phenomenon as the coverage of it often suggests.

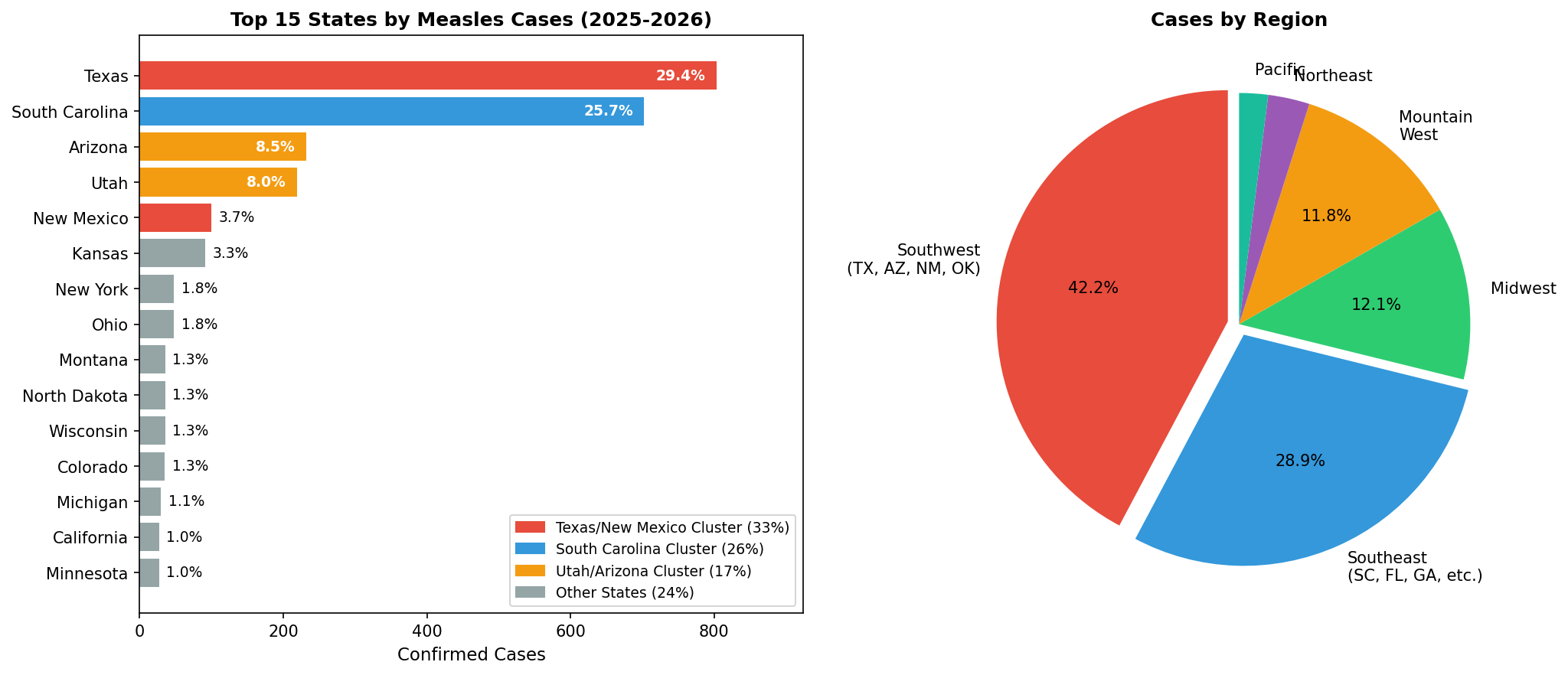

Using state-by-state case data from the Johns Hopkins Center for Outbreak Response Innovation (and some help from Claude), I took some time this morning to see where measles cases have occurred. The data clearly shows that the surge is concentrated in a handful of distinct regional clusters. Of the 2,728 confirmed cases tracked by Johns Hopkins, three outbreak clusters account for 75 percent of the total:

- Texas + New Mexico: 903 cases (33%)

- South Carolina: 702 cases (26%)

- Utah + Arizona: 451 cases (17%)

Meanwhile, 16 states have fewer than 10 cases each, combining for just 69 total cases—about 2.5 percent of the national total.

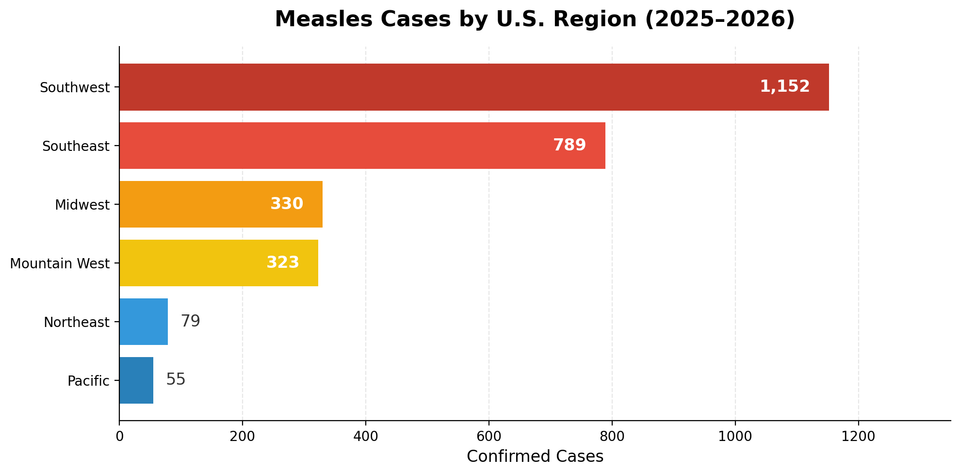

When you group states by region, the pattern becomes even starker:

| Region | Cases | % of total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Southwest (TX, AZ, NM, OK) | 1,152 | 42% | |||

| Southeast | 789 | 29% | |||

| Midwest | 330 | 12% | |||

| Mountain West | 323 | 12% | |||

| Northeast | 79 | 3% | |||

| Pacific | 55 | 2% |

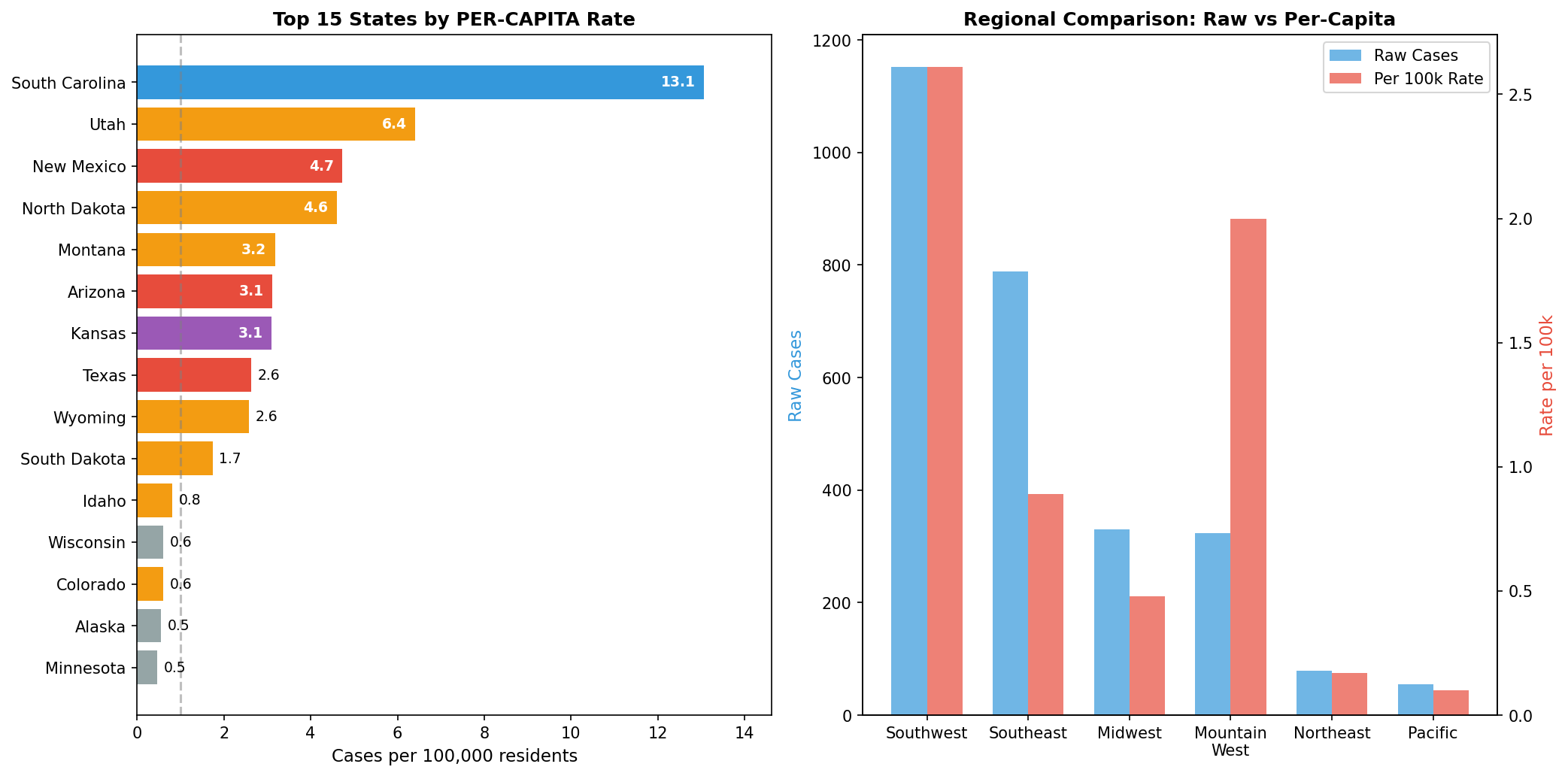

The Southwest and Southeast together account for 71 percent of all U.S. cases. The Northeast has under 3 percent, and the Pacific coast just 2 percent. And when you adjust for population, the regional disparity actually becomes more pronounced.

| Region | Rate per 100,000 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Southwest | 2.61 | ||

| Mountain West | 2.00 | ||

| Southeast | 0.89 | ||

| Midwest | 0.48 | ||

| Northeast | 0.17 | ||

| Pacific | 0.10 |

The Southwest has 26 times the per-capita measles rate of the Pacific coast, and more than 15 times the rate of the Northeast.

This is not a national outbreak. It's a regional crisis with the potential for spillover. When coverage describes a national surge in measles cases, that framing obscures what's actually happening: specific localized outbreaks in communities with low vaccination rates, primarily in West Texas, South Carolina, and the Utah/Arizona corridor. The virus isn't spreading uniformly. It's exploiting pockets of undervaccination in particular places.

The Need for Regional Cooperation

For now, the Northeast and Pacific states are holding the line. But that shouldn't be a cause for complacency. It should be a spur to action.

With messaging out of Washington on vaccination increasingly muddled and likely to become more so—Trump's CDC is blaming immigrants for South Carolina's current outbreak—the question is who will fill the void. Federal public health guidance has been the backbone of vaccination policy for decades. With that guidance now unreliable, states and regions will need to step up.

This is where regional coordination becomes essential. I've written before about what I've called the New England Option: the recognition that in an era of federal dysfunction, the most effective path forward for the Northeast may not run through Washington at all. And I've noted examples of this approach already in action, including the Northeast Public Health Collaborative, announced last year by eight states in response to shifting federal health policy.

The measles data suggests that these regional efforts matter. A disease outbreak in Boston is a public health concern in Nashua. The states of the Northeast share transportation networks, labor markets, and—as epidemiologists would remind us—disease vectors. Regional organizations like the Northeast Public Health Collaborative need to fill whatever void emerges from Washington with clear, consistent messaging and coordinated prevention efforts. These collaborations should be strengthened and become more proactive, not treated as stopgaps.

The measles map is a reminder that different parts of the country are already diverging in their public health outcomes. The Northeast has built something worth protecting. The instinct is to treat every story as a national story. But in the current climate, the smarter move may be to defend what we've built here.

Member discussion