The New England Option

As an academic researcher with at least three current and several pending federal grants, this week has left me with a particularly acute case of Trumpian whiplash of the kind I had somehow mostly managed to banish from memory during the Biden interlude. As is so often the case with Trump, the whiplash was the point.

The conventional wisdom has it that Trump reversed course on his order to suspend all federal grants and loans because of the general public outcry against it. I don’t buy it. The public outcry, the dramatic announcement and reversal, the whiplash was the point.

Trump reversed course so easily because suspending grant funds wasn’t the point. The point was to draw attention to things in the federal budget that MAGA doesn’t like ahead of the budget battle that awaits the expiration of his 2017 tax cut. The grant cancellation stunt was designed to set up “wasteful” and “woke” programs for elimination in negotiations over how to pay for tax cuts, and to get "the libs" to howl about it.

This connection between threats to programs that matter to me and the taxes I pay has me returning to a question that, ever since the election, and even before it, I just can’t shake: What are we — Blue Staters, Connecticut people, New Englanders — actually getting out of our federal union these days? Beyond a few things like national defense and a stable currency, what does a big federal government, to which we contribute so much more in taxes than our fellow citizens in Red America, provide us that we couldn’t provide better, and with less rancor and uncertainty, ourselves?

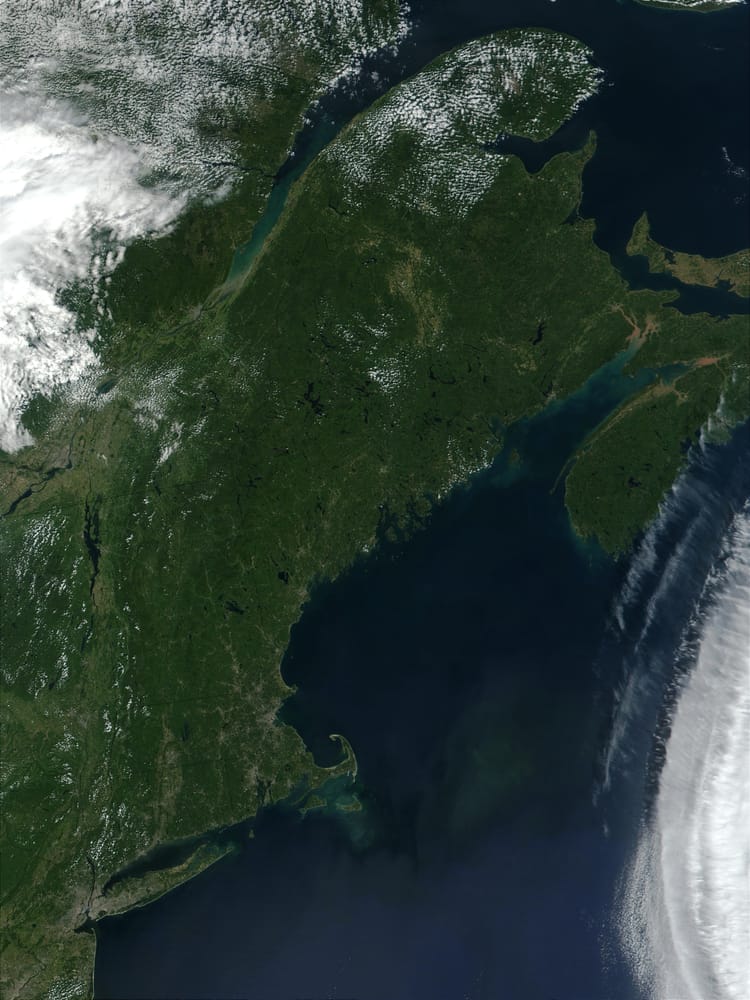

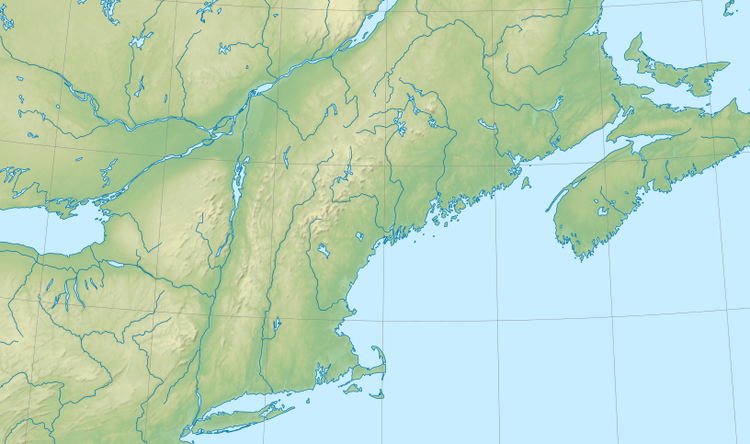

To look at the 2024 election map is to see that aside from the densely populated areas of the West Coast, a very narrow strip of the coastal Mid-Atlantic, and New England, it’s Trump’s America. The only reason the popular vote was even close is because, as with all recent elections, Blue States continue to vote decisively against Republicans.

But the fact that it's always close seems to matter less and less. The hard inequality of the Electoral College and the hardening Republican control of a majority of its seats, along with MAGA's utter shamelessness, puts paid to that idea. MAGA has assumed a mandate, and its disregard for political norms and the law means it will probably be able to act on it effectively.

We will see this first and foremost in the tax bill, which, however skillful the Democratic Congressional opposition, will undoubtedly end up favoring Trump’s voters. We will see an even larger share of revenues come from Blue States and a larger share of expenditures flow to Red States, or at least to things that MAGA cares about. All this will come at the expense of things we — Blue Staters, Connecticut people, New Englanders — care about.

In the face of this reality, it seems to me that we have two choices.

We can either change our politics to appeal to a national electorate and win national elections. (This was essentially the Biden strategy, and it didn’t work.) Or we can stay true to what we believe and lose national elections. We can say and do things that will appeal (perhaps) to “persuadable” Trump voters and win the Presidency. Or we can be who we are and lose it.

Maybe we should just lose.

That isn’t as hopeless as sounds, nor does it mean giving up on our principles. Our federal system offers an alternative. We can shift our focus from national politics to state and regional politics and implement our values locally. If the rest of the country wants MAGA’s weird mix of lies, bigotry, sexism, MMA, glitter, Russophilia, corruption, etc., why shouldn’t they have it? We, meanwhile, can have the things liberals value: strong institutions, good education, protections for women and minorities, labor rights, an independent press, clean energy, and the rest.

But we have to vote our local interest.

What does voting our interest mean? It means voting for what’s best for us, even if that means other parts of the country will get worse. It means giving up on the notion that we can will the rest of the country to be better.

This looser vision of federalism means prioritizing things that will be good for the states in our regions rather voting for things we think would make the whole United States better. Sometimes that will mean voting in Congress with fellow liberals from across the 50 states. But often it will mean voting against them. If voting with right wing crazies in Congress on a particular piece of legislation is good for our local or regional interest, then maybe we should do it.

This brings us back to taxes.

If MAGA truly wants to slash federal taxes and spending (or replace the income tax with tariffs or whatever other crazy nonsense is on tap this week), then maybe we should take him up on it. New England pays out much more in federal income tax than we receive back from the federal government. Drastically defunding the federal government would lead to massive cuts in federal programs (like the ones that fund my research), but couldn’t we replace them locally or regionally with correspondingly increased state taxes?

Couldn’t we, for instance, offset the regressive, inflationary effects of the Trump tariffs on the working class with a drastically higher minimum wage? Or say Republicans in Congress want to kill Amtrak to fund federal tax cuts for the wealthy. Shouldn’t we help them? The Northeast corridor subsidizes the rest of the Amtrak system. And those tax cuts will flow disproportionately to Blue States. Who knows? Maybe we could spin off the Northeast Corridor as regional co-op and have reliable high-speed rail between Washington and Boston if we weren’t paying to keep empty trains running between Omaha and Cheyenne. If Blue States aren’t funding programs for Red States who clearly don’t want them in the first place, then maybe we could enjoy both lower overall tax rates AND better government.

It’s reasonable to ask whether individual states are too small and weak to carry out big programs like transportation, health care, and social security. And maybe alone they are. But if even just New England, New York, and New Jersey banded together in a regional resource sharing coalition—a kind of statutory sub-federal union—you’d be looking at an economy bigger than all but a one or two European countries. If they banned together to vote their regional interest in Congress, their 16-vote bloc in the Senate would be enough to offer whichever national party gives it the best deal a Filibuster-proof majority.

These are the states with the best schools, wealthiest corporations, best transportation infrastructure, and strongest institutions. It has always been a pipe dream of progressives to turn the United States into something resembling Denmark or Sweden. If we didn’t know it already, the last few elections should show us that that’s not what the rest of the United States wants. But that is what Greater New England wants. That is what the Pacific Coast wants. Why shouldn’t we have it?

Since the Civil War, our political imagination has focused on the whole of the country. Our primary politics has been a national politics and national political alignments have defined political alignments in the states and localities.

We are attached to the idea of a national politics for good reason. The idea that the appropriate field of political attention and action is the whole country—the Union—allowed us to rid the country of slavery and Jim Crow in the 19th and 20th centuries. It’s the idea that finally brought electricity and jobs to the poor rural communities of the Southeast and West.

But today is not 1850 or 1950. For one thing the country is much, much bigger. And the regional disparities in justice we face today do not have the same urgency as those presented by slavery, segregation, or even the Appalachian coal mines of a century ago.

It’s true that shrinking our political attention from the whole United States to just our individual states and regions will leave lots of vulnerable people in other parts of the country unprotected. It’s also true that this New England Option will mean abandoning many of our Blue brethren in the Red wasteland we leave behind. I admit that this isn’t great. But is sticking together really helping those folks if we can’t win national elections? It’s certainly not helping those of us in places with strong liberal majorities.

More optimistically, I am confident those Red States will ultimately come to regret their choices as the consequences of those choices are made clear to them by our diverging fortunes. They don’t seem to want what we’re selling. But maybe they will if we stop selling and start showing them what a really dynamic, just, and wealthy country looks like.

We rarely anymore think about what’s best for our individual states or about our differing regional interests. But doing so — and voting so with whomever’s immediate interests align with ours, regardless of their ideological or national commitments — would open up avenues to make our states and regions what we want them to be, what they could be. Rather than tying our fortunes to parts of the country who fundamentally don’t want what we want, we can go our own way. Doing so would at least give us the chance of proving the superiority of our model. Seeing what our commitments to progressive taxation, social welfare, education, the environment, diversity, justice, and strong institutions can do may help them turn away from the scapegoating and lies that stand in for governance in Trump’s America. When they see what we see, when they come around, we can reunite as old friends.

And, hell, in the meantime, they’re always welcome to move here.

Member discussion