AI Coding Collaboration for Digital Humanists (and Other Competent Imposters)

Author's note: This post is the first in a series on AI Coding Collaboration for Digital Humanists (and other competent imposters). The series chronicles the development of AcadiMeet, a scheduling application designed for the particular needs of university faculty and staff members, built from concept to production over five sessions with an AI partner. It extracts from my chats the strategic methods, communication patterns, and architectural principles necessary for domain specialists—who know what to build but may lack current coding fluency—to successfully launch a software development project with the help of generative AI.

As I said in my previous post introducing my new web application, AcadiMeet, although I have spent the past fifteen years managing teams of web and software designers and developers, my own days of coding had long been relegated to memory. Whenever I thought to take on a new project, the barrier to entry always felt too high. Too many new technologies had passed me by, and I had forgotten too much of the old ones I once knew. This is the condition of what I will call the "competent imposter", a domain specialist who knows what to build but has lost the knack for how.

That feeling changed when I started on AcadiMeet with the help of a large language model. To my huge surprise, it took five sessions to go from an abstract idea to production application. And perhaps the biggest surprise was what didn't happen in the first session.

The First Session is for Thinking

The instinct of any competent, but rusty or out-of-their-depth, solo developer is to come at a new project with specific list of technical questions like "what database should I use" or is "React better than Vue?" That approach makes sense if you're starting with a book (I remember the days when page 1 of an O'Reilly book was your best starting point) or with Stack Overflow or with a more knowledgable friend. You're trying to do this on your own, after all. You're not looking to impose on kind strangers and friends. You need simple questions that require only simply answers.

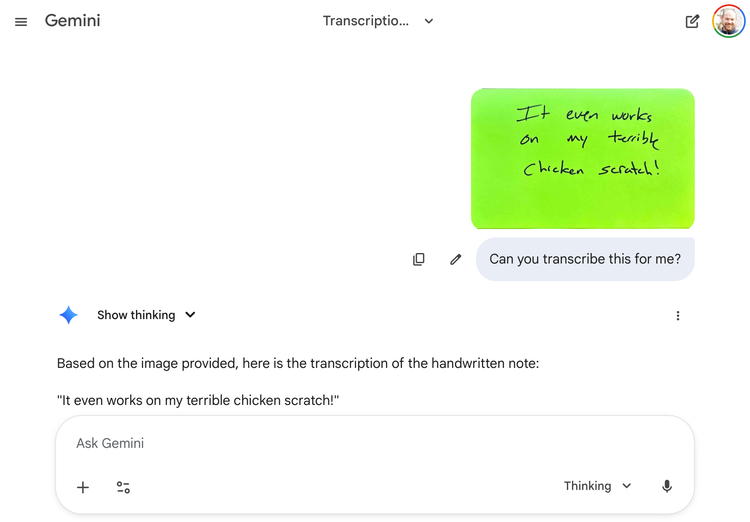

But AIs aren't like friends. They don't run out of time, they don't get tired, they don't get annoyed with you or sick of your project.

That means there’s no need to get right to the point, and remarkably, in the first of my five, roughly four-hour long (usually not in one sitting) sessions with Anthropic's Claude, I didn't write or receive a single line of code.

Instead, likely in part because I was so oblivious to the how, that entire first conversation was dedicated to describing the what and the why. Here's the first prompt I gave Claude:

I want to build a web application to replace Doodle and whentomeet, specifically for university faculty and staff. Users would prepopulate the dates of their semester, their teaching times, and a link to their Outlook or Google Calendar. They would also be able to block off hours when they are unavailable for other reasons, including writing, research, or personal reasons—perhaps called "my time."

Notice the omissions. I didn't ask about a tech stack, a database schema, or really any technical details. I just gave Claude my vision, in as much detail and with as much specificity as I could.

The Socratic Method of Software

The subsequent conversation became a design tool in itself. Starting this way—with the vision—pointed Claude down a path that forced me to clarify that vision, including my goals for the project, my audience, and their needs. Predictably, I guess, Claude's response to my interest in aims and outcomes was not a block of code, but a series of penetrating questions. (In this regard, I think my use of the word "perhaps" was unintentionally productive as it signaled to Claude that I wasn't really quite sure what I wanted yet.) This dialogue was the most valuable part of the first session, as it quickly surfaced ambiguities and conflicts in the concept. Some of Claude's questions included:

- How much of someone's "my time" reasoning should be visible to others?

- Should the app support recurring meetings?

- Should external collaborators need accounts, or should the app allow guest responses?

In answering these questions, I was forced to clarify my own thinking about the application's core identity. For instance, clarifying that "my time" reasons must be completely private immediately established (for me and for Claude) that one of AcadiMeet's core design principles would be "privacy-first." That and other philosophical foundations that emerged from this first no-code session would ultimately guide every technical decision that followed, from the user interface to the database design.

Key Lessons for The Competent Imposter

For the digital humanist, project manager, or other "competent imposter" coming from outside of engineering, this process provides a profound sense of empowerment. I may have forgotten how to write code, but (especially now in my 50s) I'm pretty good using language to explain what I want.

I suppose it shouldn't surprise me that starting with high concept decisions would be so productive. The best designers and developers I have worked with have all put me through this kind of Socratic ringer before they started building. Explaining a problem in detail, before you ask a developer for a solution, clarifies the solution in both your mind and theirs.

By starting this way you are leveraging the AI not for its coding prowess (yet), but for its capacity as a structured listener. If you can walk away from your first "AI coding" session with a well-defined problem, a good sense of your user, and a desired outcome, you've succeeded.

Member discussion