AI Lessons from 1999

This semester I gave my students a pencil and paper final exam, as I've done since the beginning of the generative AI era. And being a dad, I handed out the blue books with the same dumb joke I've used since 2023: "Tonight we're going to party like it's 1999."

The students don't get it, of course. Prince died before most of them were born. But the joke keeps landing for me because the last few years since ChatGPT broke out have felt like nothing so much as the late 1990s, at least for those of us who came up in the era of Web 1.0. I've noticed all the same enthusiasm, possibility, and fumbling, but also all the same fear, ethical concern, and pushback of that era.

The Divide

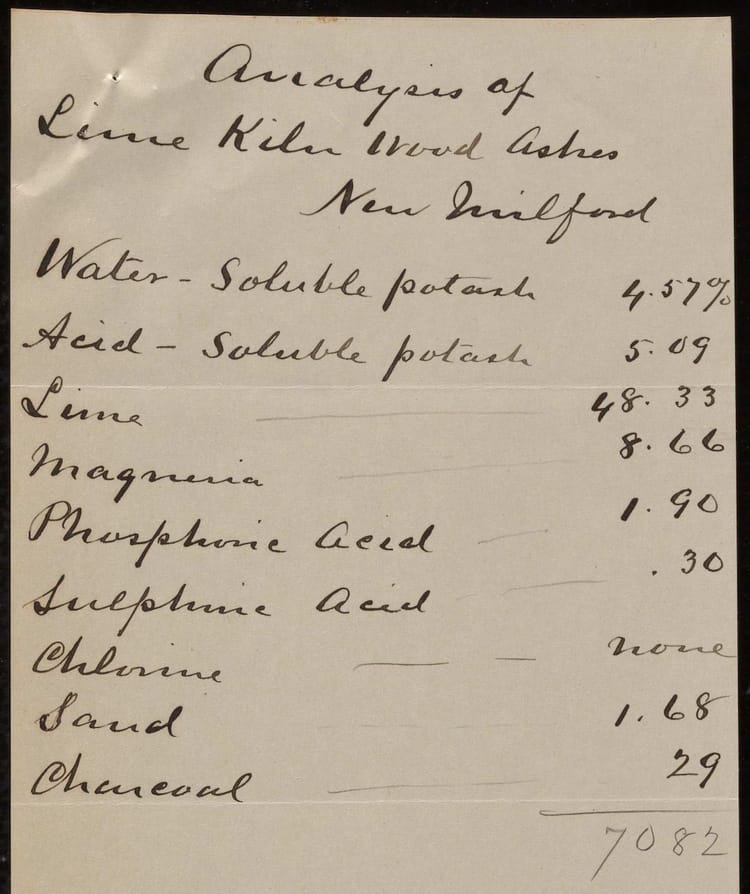

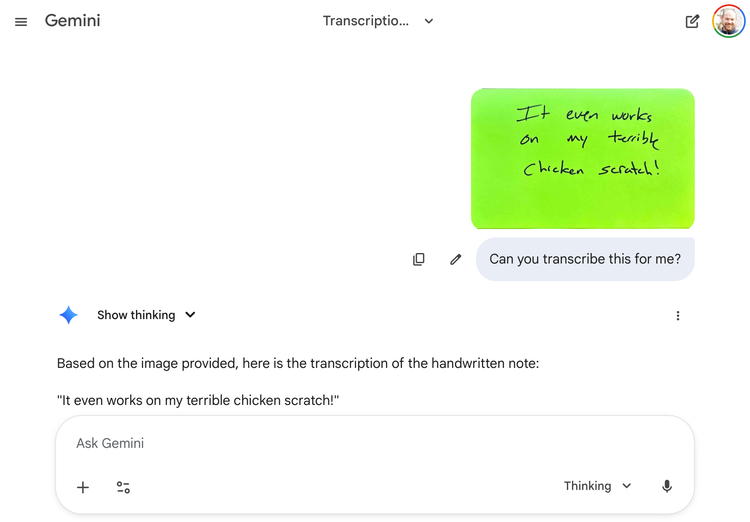

The pushback is real. There is tremendous hostility to AI in the higher education and cultural heritage communities. The reception my recent post on "Seeing Old Science" received on Bluesky is a case in point. I wrote about how Gemini's ability to read handwritten documents could unlock scientific data buried in agricultural extension records. The responses ranged from thoughtful skepticism to outright hostility—accusations of naivety, of ignoring the environmental and labor costs of AI, and even of being a tech company shill despite my career-long commitment to building open source software for education and cultural heritage.

Some of this critique is legitimate. I take concerns about AI’s environmental costs, labor implications, and extractive training practices seriously. But what struck me wasn't the substance of the critiques. It was how many of them seemed to come from people who had formed their opinions when ChatGPT launched in 2022 and hadn't updated them since.

This dichotomous response isn't unique to our field. It's true across the broader discourse. In "Looking back at a year of AI cope and progress," Kelsey Piper makes the point bluntly:

If the only time you've used ChatGPT was when it came out in 2022, or even if you haven't used it in the last six months, I'm sorry, but you have no idea what you're talking about. I've heard so much AI cope that has been thoroughly invalidated.

She continues:

But if AI is a bubble, it will be in the way that the internet was a bubble in the late 1990s. Yes, some people got out over their skis, but also, it's a world-changing technology, and the successful companies are going to be worth far more than anyone is going to lose in the current investment cycle. But sometimes when people claim that AI is a bubble, that's less a specific falsifiable claim about overvaluation and more just another way for them to say they hate AI.

The problem, as Piper sees it, is that while skeptics have been busy dunking on the most aggressive predictions, AI has actually improved far faster than almost anyone else predicted. "Assume things will proceed a little slower than the most aggressive estimates show—but only a little slower" turns out to have been a much better heuristic than "assume all this AI nonsense is about as good as it's going to get."

There's a huge divide between people who, often for legitimate ethical reasons, have rejected AI outright, and people who, while they may share those ethical concerns, believe a better response is to experiment widely and try to shape the technology's development. This divide feels familiar because it's the same split we saw in 1999.

We've Been Here Before

It's hard to remember now, but in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the fear that the new all-connecting technology of the World Wide Web would consume us was real. The Matrix came out in 1999, and its vision of humans as batteries for machine intelligence struck a nerve. The journalism business spent those years rejecting online distribution and screaming at Craigslist for destroying the classified ads revenue stream newspapers had relied on for decades. Publishers insisted that "content wants to be paid for" and built paywalls that nobody wanted to navigate. Most of them failed.

This was true in our fields as well. Remember when everyone rejected Wikipedia because it was going to ruin teaching and scholarship? Remember when cultural heritage organizations debated whether they should have online collections at all? There were serious, sustained arguments that putting collections online would cannibalize physical visits, that digital surrogates would be mistaken for originals, that the web was fundamentally unsuited to scholarly work.

It seems obvious now that Wikipedia and online collections are useful things. But it wasn't obvious then. The arguments against them were made in good faith by smart people who saw real risks. What they missed was that the question wasn't "should we adopt this technology?" but "how do we shape it?"

One of the last things my mentor Roy Rosenzweig wrote before he died was "Can History be Open Source? Wikipedia and the Future of the Past." Roy didn't dismiss concerns about Wikipedia—he took them seriously and addressed them systematically. But his conclusion was that historians needed to embrace Wikipedia and experiment with different approaches to using it in teaching and research. Rejection wasn't a strategy. It was an abdication.

Clay Shirky made a similar argument about journalism in his 2009 essay "Newspapers and Thinking the Unthinkable":

The answer is: Nothing will work, but everything might. Now is the time for experiments, lots and lots of experiments, each of which will seem as minor at launch as craigslist did, as Wikipedia did, as octavo volumes did.

In both areas—journalism and higher education—the institutions that survived and thrived weren't the ones that rejected the web. They were the ones that experimented relentlessly, failed often, and learned quickly. The answer to the challenge of the web wasn't to build higher walls. It was to try everything.

Try Everything

I believe the answer to the challenge of AI is the same: we need to try everything, not reject it wholesale. This doesn't mean uncritical adoption. It means serious, sustained experimentation informed by our values and our expertise.

Dan Cohen has been modeling this approach at Northeastern. In "AI and Libraries, Archives, and Museums, Loosely Coupled," he argues that rapprochement between cultural heritage institutions and AI is possible, but only if we stop treating AI as monolithic:

AI is... a constellation of approaches and technologies, not just the training-and-generating of the latest large language models, and in the past year, a new way of associating less generative, more research- and learning-oriented aspects of AI with the unique and important materials in cultural heritage institutions has emerged, one that holds the potential for a less extractive, more controlled, and ultimately more fruitful interaction between this new technology and cultural collections.

Dan's response to the ethical dilemmas of AI at Northeastern hasn't been to build defenses. It's been to experiment—to create "The Library's New Entryway" where students and researchers can engage with AI tools in ways that are transparent, controlled, and aligned with scholarly values.

Ted Underwood makes a similar argument in "AI Is the Future. Higher Ed Should Shape It." If we're not actively experimenting with these tools—if we're not in the room where they're being developed and deployed—we forfeit our ability to influence how they develop.

Even critics are experimenting. Miriam Posner, who has serious reservations about AI, nevertheless created "ChatGPT Harm Reduction for Writing Assignments," a practical guide for instructors trying to navigate teaching in the age of generative AI. She's not endorsing the technology. She's taking it seriously enough to develop thoughtful responses.

This is what I mean by "try everything." It's not uncritical enthusiasm. It's the recognition that informed critique requires engagement. If you're not using the latest paid models regularly, if you formed your opinion in 2023 and haven't updated it, you're critiquing something that no longer exists. Indeed, maybe I should have named this post after the Shakira song rather than the Prince song.

Back to 1999

In 1999, there were no answers. Everyone had to roll their own website, build their own collection database, and figure out what metadata standards made sense for their materials. Faculty had to experiment with what online tools meant for teaching. Some assigned students to edit Wikipedia, some banned it entirely, but most fumbled around in between.

The institutions that thrived weren't the ones that waited for best practices to emerge. They were the ones that tried things, failed publicly, learned quickly, and tried again. They were the ones that treated the technology not as a threat to be resisted but as an opportunity to rethink fundamental assumptions.

This is just like today. There are no standard platforms for AI in education or cultural heritage. There are no established best practices. The ethical frameworks are still being worked out. The technological capabilities are still rapidly evolving.

As Shirky said about the web: nothing will work, but everything might. As Shakira sang: we need to keep "making those new mistakes." As Prince sang: we need to party like it's 1999.

This doesn't mean abandoning our values or ignoring the legitimate concerns about AI's environmental and economic costs. It means bringing those values and concerns into the experimentation. It means shaping the technology rather than being shaped by it.

Member discussion