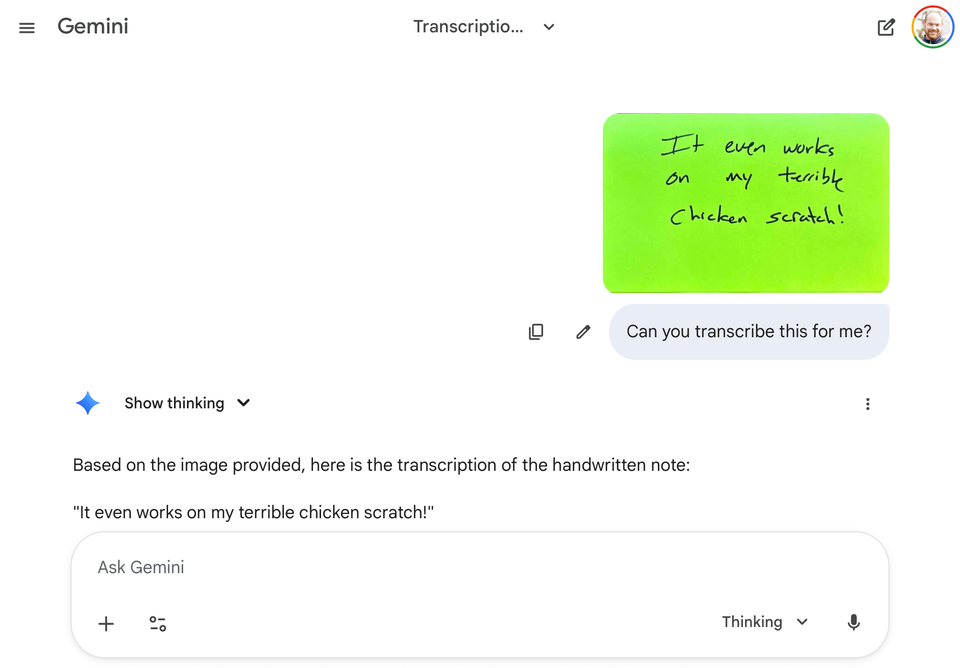

Handwriting Recognition Roundup

Something remarkable has happened in the past few weeks. Google's latest LLM, Gemini 3.0, appears to have solved handwriting recognition. Not just improved it—solved it. And we're not just talking about low hanging fruit. We're talking about very old documents, documents in relatively minor languages, and documents with complex tabular data like ledger books. Documents in bad condition. Documents with terrible handwriting. Documents with marginalia. Documents with different types of text in different hands going in different directions. And by all accounts, it's doing this better than the best human-trained models and even better than actual humans trained in paleography at a graduate level.*

Gemini is also substantially better at this than its competitors from OpenAI and Anthropic. So if you've been using ChatGPT or Claude for transcription with mixed results, it's time to abandon your priors and try Gemini.

I think it's safe to say that most historians and archivists are skeptical—even resistant—to AI, and for good reasons. The extractive training practices, the environmental costs, the annoying hype cycle, and the threat to human expertise are all real. I share these concerns. But this is a use case I think we need to take seriously, one that should force us to rethink some fundamental assumptions about what's possible in archival access.

What the Evidence Shows

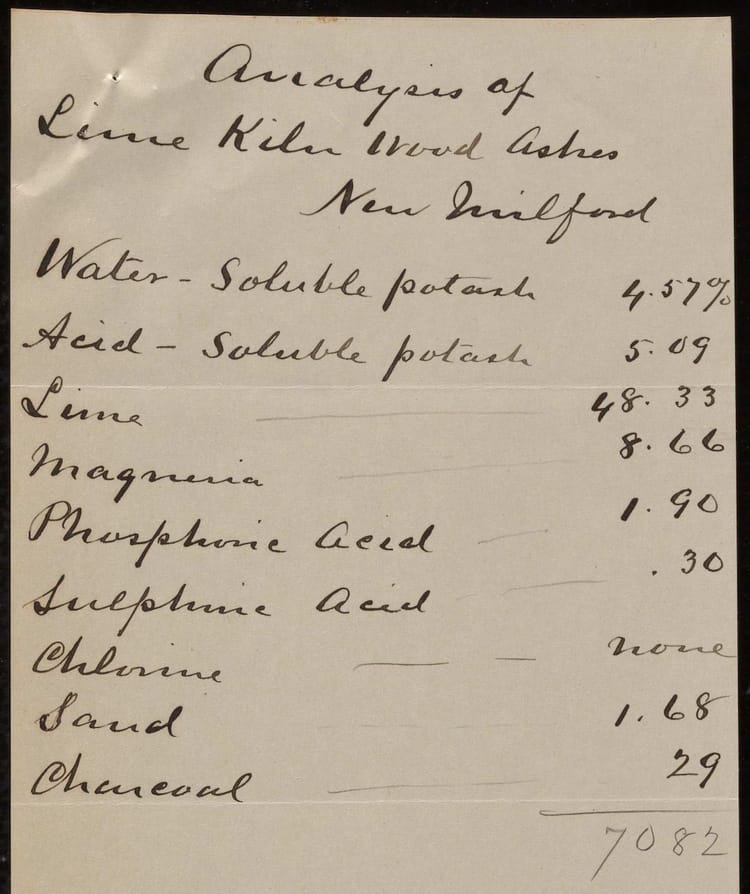

Start with Mark Humphries's experiments on his Generative History substack. In "The Sugar Loaf Test: How an 18th-Century Ledger Reveals Gemini 3.0's Emergent Reasoning," he describes testing Gemini's ability to read and reason through complex early modern ledger books. He even tries to trick it into using an imaginary currency in its analysis. Gemini pushes back, using the mathematical logic embedded in the ledgers to insist that the currency must be pounds sterling.

Humphries writes:

At the very least, the evidence presented here suggests that Gemini 3.0 is doing something more sophisticated than statistical pattern recognition. First, we saw the model correctly infer hidden units of measurement by running what appeared to be complex, multi-radix mathematical checks against the prices in the document—a process that looks a lot like symbolic reasoning. When confronted with an adversarial prompt that tried to force a fictitious currency onto a real historical document, the model pushed back using the internal logic of the document to argue mathematically and ethically that my prompt was factually incorrect.

In a follow-up post, "Gemini 3 Solves Handwriting Recognition and it's a Bitter Lesson," he systematically benchmarks this performance against other models—including human-trained models and actual humans. Gemini substantially outperforms everything that's come before.

Colin Greenstreet confirms these results in "A New Lens into the Archive":

I can confirm everything Professor Mark Humphries has said in his two important Substack posts (Generative History), and more. Especially for non-archivist and non-librarian users like me, interested in transcribing our own research collections of a few images up to tens of thousands, wanting flexibility and control of work flows, and the ability to summarise and enrich those transcriptions on the fly as part of our historical research.

And Dan Cohen, writing in his newsletter, captures what I think is the ultimate significance of this moment in "The Writing Is on the Wall for Handwriting Recognition":

At this point, AI tools like Gemini should be able to make most digitized handwritten documents searchable and readable in transcription. This is, simply put, a major advance that we've been trying to achieve for a very long time, and a great aid to scholarship. It allows human beings to focus their time on the important, profound work of understanding another human being, rather than staring at a curlicue to grasp if it's an L or an I.

What This Means

If these accounts hold up—and the evidence so far is compelling—we need to revisit lots of old questions.

For example, perhaps funders of the humanities (IMLS, NEH, Mellon) and even the sciences (NSF, NIH, Sloan, Schmidt) should take another look at mass digitization projects. At the start of the internet age, during the late 1990s and early 2000s, there was substantial funding for mass digitization. That money largely dried up when people realized that the speed at which humans could describe and catalog digitized materials couldn't keep up with the scanners. This was especially true of handwritten materials that weren't amenable to OCR.

But now that AI can read handwriting—presumably at scale—perhaps we should revive the dream of putting everything online. Not just the already-famous collections, not just materials in major languages, not just the stuff that's easy to process. Everything.

There are, of course, thorny issues about accessibility, control, labor, and interpretation that historians, archivists, and developers will need to work out together. The computational, environmental, financial, and institutional costs will be real. And we still don't fully understand what it means to have AI as an intermediary between researchers and primary sources.

But that's exactly why we can't afford to keep our heads in the sand. These new results mean we need to get down to business and start talking. Not yelling at the technology and its admittedly problematic makers. But actually talking with each other about how we want to shape its use in service of historical research and public access to cultural heritage.

Because like it or not, a new world for archives and historical scholarship is here.

* I feel kind of terrible for the good folks at Transkribus, who have done, and continue to do, amazing work with human-trained transcription models. But I'm pretty confident that there will be room in the new paradigm for the careful, specific work their models perform.

Member discussion