Innovation as Habit: Practicing looking forward in a backward-looking business

The following are lightly edited speaker notes for a talk I first delivered in October 2024 at the Greater Hudson Heritage Network's annual meeting at Reid Castle on the campus of Manhattanville University in Purchase, New York and recently reprised for the Grant Professionals of the Lower Hudson Valley. Thanks to my team at Greenhouse Studios, especially our senior Design Strategist, Brooke Gemmell, for images related to Greenhouse Studios projects. Apologies for any typos or other errors.

Today I'm going to talk about innovation. But I'm going to talk about it somewhat differently than you probably usually hear it talked about. When we hear about innovation, most often it's in the context of science, technology, engineering or medicine, very often in the context of business, and indeed some of my examples will come from these fields.

But innovation isn't something that some fields have, and other fields lack. Innovation can, and does, come from anywhere. Indeed, we are all innovating all the time, whether we recognize it or not. One of the things I hope you take away from this today is to how to recognize it and to make a habit of recognizing it.

Nor do I think being innovative is a personality trait that some of us have and some of us lack. I don't think that there are innovative people and not-innovative people. Being innovative isn't something inherent --something we're born with or not -- and can't change.

Instead, I think that being creative is the product of certain behaviors, certain habits of mind, certain ways of being in the world. Just as being healthy isn't something you have but something you work at, being creative isn't a fixed trait. It is not something you are, but something you do.

Moreover, it isn't something you do just once. You don't eat cheeseburgers every day for lunch and then one day have a salad and say, "Super! Job done! I'm healthy now." No, you have to pick the salad consistently over time. And exercise. And get enough sleep. That's how you become healthy.

Being innovative is like that. It's something that you have to repeat. It's something that you have to practice. It is a habit.

And that’s true of both individuals and institutions.

So, what does the practice of innovation look like? What are the repeated behaviors that cultivate creativity? What are the good habits we have to foster? And what are the bad habits we have to break? What are the habits that promote innovation and what are the habits that stifle it?

Today, I'll start by offering three healthy habits, practices we should cultivate both in our individual creative lives and in our organizations. I'll illustrate the power of these habits with some examples from the history of technology and from my own work.

Then I'll turn to three unhealthy habits we should avoid.

Afterwards, I’ll take questions about how we might use these lessons in innovation to meet the challenges of a fast-changing world, for example the challenges of disruptive technologies like artificial intelligence or of an increasingly hostile political environment.

Good Habit 1: Operationalize your byproducts. Make the leftovers the meal.

In the process of building anything, of making anything, of doing anything, we end up with byproducts. Whenever we engage in our main activity (perhaps it's fundraising, perhaps it's grant making, perhaps it's financial planning) we produce a lot of stuff. Some of that stuff is our main product, our final output. But some of that stuff is process, interim products that get us to our final output. Filmmakers talk about "B-roll" or "the cutting room floor" -- images that will never appear on screen but were necessary to capture to achieve the final cut.

For you maybe that leftover stuff isn't b-roll. Maybe it's a proposal workflow, maybe it's a reporting process, maybe it's a client database, maybe it’s a financial strategy, maybe it's a set of email templates. I'm not in your workplace, so I can't say for sure. But what I can say for sure is that one of the habits of truly innovative people and organizations is that they make use of those leftovers. They keep them, they remember them, they recycle them.

Probably the best example of this habit of operationalizing byproducts is Amazon and its Amazon Web Services platform. Many of us still think of Amazon as an online bookstore and retailer. But for at least the last several years, retail has made up a minority of Amazon's overall revenues. A much larger share comes from Amazon Web Services.

Amazon Web Services is a service that Amazon sells that allows you to user its server architecture (its databases, its middleware, its web servers, its storage, its security and privacy controls) to run your own websites and web database applications. Before AWS, most companies ran their websites on hardware they owned themselves, using software and storage they installed and maintained themselves. Today, most companies run their websites "in the cloud," that is using Amazon's hardware, software, and storage (or similar offerings from Google, Microsoft, or Oracle). For a relatively modest cost, Amazon Web Services lets you use the same service architecture that runs its Amazon.com e-commerce operation, Kindle Books, Prime Video, Alexa, and all its other product offerings.

Some of you are old enough to know that in its earliest days, Amazon was primarily an online bookstore. It soon branched out into selling other things, which was a fairly obvious move. If you get good at managing the databases, user interfaces, marketing, supply chains, inventory systems, and logistics of selling and shipping books, why not apply those aptitudes to selling other stuff?

Unlike some other early dot-com era Internet companies, Amazon was particularly and singularly focused on growth -- growth at the expense of other business values such as profit taking or exit strategy. Indeed, for most of its history, despite its size and market dominance, Amazon has run at a loss as it put its revenues into building the technical and infrastructural capacity to grow ever larger. For at least its first two decades, Amazon's focus was always on making preparations to be bigger next year, which meant building excess capacity -- more warehouse space, more workers, more web servers, and a more robust web services architecture than it actually needed at the time. It always had room to grow.

In the mid-2000s, the team who ran this bigger-than-necessary web infrastructure, led by Andrew Jassy, had a realization. What if we allowed other, smaller companies use our excess capacity and the world-class infrastructure we've built? What if we allowed them to use our servers, our storage, our database architecture, our development tools, our security adaptations for a fee? What if instead of buying and running hardware and hosting their own e-commerce website, we let them use our superior technology at a lower cost? After all, we already have all this excess space lying around.

For most smaller Internet organizations, including mine, it was a no brainer. You'd have to be crazy to keep that aging Dell and its rickety homespun web server running in the closet when you could simply use Amazon's vastly better technology for pennies.

Today Amazon Web Services is the largest part of Amazon's business. Amazon isn't an online bookstore anymore. It isn't really even an online retailer. It's a technology services company. It's telling that when Jeff Bezos stepped down as CEO, the person who succeeded him was Andy Jassy, the technology team leader who launched AWS.

The point here is that Amazon didn't build a way-to-big technical infrastructure in order to launch a web services business. They did it to facilitate growth. But they were self-aware enough to realize that that excess technical capacity could be repurposed, that the byproducts of their e-commerce business could be operationalized. In the end, that byproduct became Amazon's main product, and Amazon has repeated that move time and again, allowing other companies to piggyback on their advanced logistics systems and using its expertise in dealing with book publishers and intellectual property licensing to launch Amazon Prime Video. Today the bookselling business isn’t much more than a nice sideline for the company.

Let me give an example of this practice of operationalizing your byproducts that's a little closer to home.

For the past few years I have been working with colleagues at Smith College on a project we're calling, “What Women Wore.” The project grows out of work that an early-career museum curator named Nancy Rexford did in the 1970s and 1980s. With apologies to Nancy for what is surely going to be a somewhat mangled secondhand retelling, Nancy's story is a great example of operationalizing byproducts.

In 1975, Nancy went to work at Historic Northampton (MA) as one of its only paid employees. On her first day on the job, Nancy received a tour of the historic house from the Director, who showed her around the house and introduced her to the exhibits and collections.

Nancy noticed, though, that the Director never took her to the third floor of the building. At the end of the day, Nancy asked, "What's on the third floor." The Director responded, "We don't go up there."

"You don't go up there?" she asked.

"We don't even know what's up there," he responded.

The next day, Nancy went up there, where she found an attic full of steamer trunks packed with ladies' clothes: dresses, shawls, undergarments, outerwear, caps, and shoes. And it was all just piled into these boxes. Nancy made it her business for the next decade to figure out what was there.

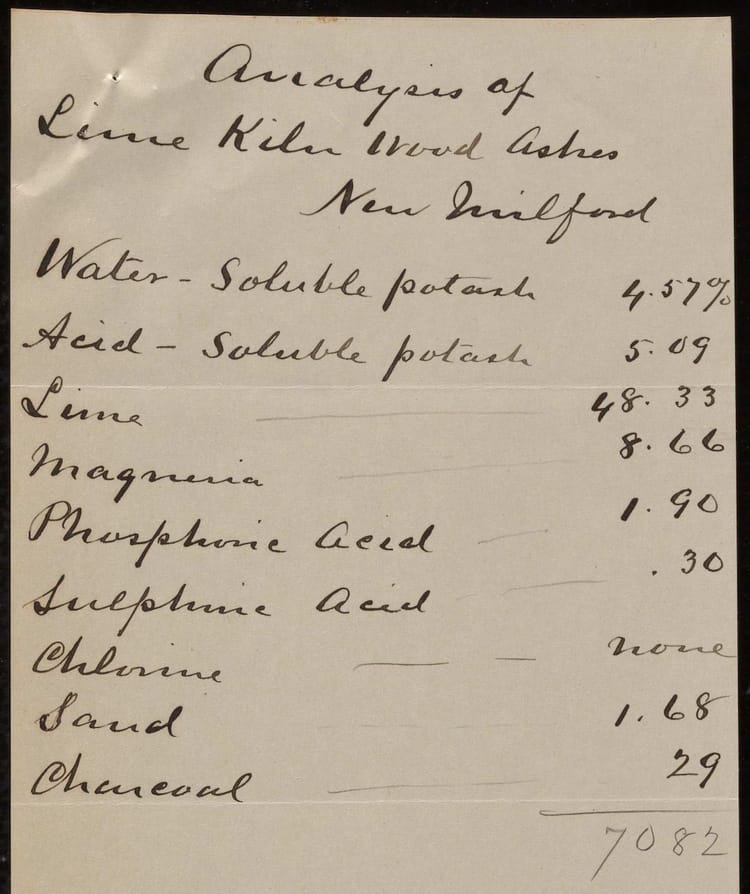

To do that, Nancy undertook a research project of enormous scope. of research. None of the items in the trunks were labelled. Nancy might be able to tell that something was a cap, but there was no indication of when it might have been worn and by whom. She needed a system for indentifying the materials.

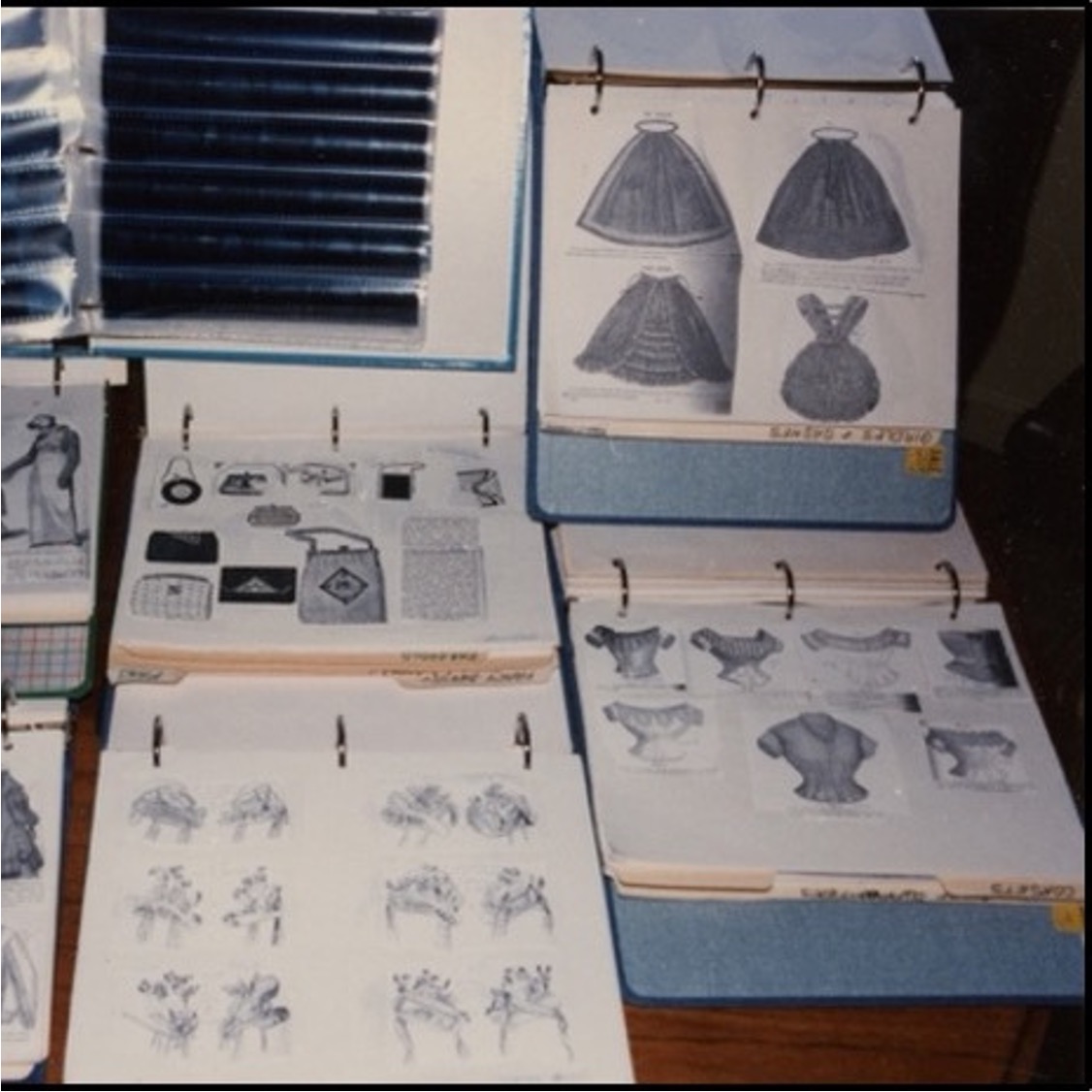

Nancy turned to the library where she found bound volumes of ladies magazines that first appeared in the American press around 1790. She went to work photocopying all of the fashion plates that those magazines contained, all the pictures of dresses and skirts and blouses and jackets and caps from 1790 up to about 1930. She organized these hundreds of photocopies by clothing type and date, and pasted them in notebooks. Nancy ended up, for example, with scrapbook of photocopies of caps that ran the course of the 19th century, showing the evolution of ladies' headware across time. She had another for jackets, another for dresses, another for fringes, and on and on for every garment type. Since ladies' magazines in the 19th century tended to be published seasonally, to advertise the latest fashions, and since fashion changes gradually over time, Nancy's notebooks allowed her to track the evolution of each garment type with great specificity, just as a paleontologist would track the evolution of a species by placing fossil specimens in chronological order.

In the end, Nancy assembled a collection of more than 70 notebooks that enabled her to grab an item of clothing from one of the trunks, compare it to the photocopied in her series, and provide it with an approximate date and, in some cases, a sense of the social position of the person who had worn it -- just as a paleontologist identifies a newly found fossil.

For the past several years, I have been working with Nancy and colleagues at Smith College's Historic Clothing Collection to digitize Nancy's notebooks, organize the images in a searchable database, and provide access to historians and curators worldwide. So let's say, for instance, you're a historian who's looking at an undated, unsigned portrait of a woman from the 19th century. The “What Women Wore” online fashion plate index (for which we’re actively seeking funding) would help you match various features of the clothing items in your painting (the pattern of a lace fringe, for example, or the length of a sleeve) to images in Nancy’s notebooks and thus to assign a date to the portrait. And because Nancy's series is so complete and so detailed, that date would be accurate within a year or two, sometimes a season or two, rather than the decade-level precision the average 19th century historian might achieve by eyeballing it. Ultimately, we are aiming to use intelligent image recognition to allow you to upload a picture of a garment and have the system automatically suggest some possible matches and directions for further research.

Nancy never intended for her notebooks to be used for anything but her own task of figuring out what was up in that attic. But what started out as simply a tool for producing a product -- an accurate catalog of Historic Northampton's clothing collections -- has, through Nancy's hard work, become a valuable product in its own right.

I'll offer just one more example. My lab, Greenhouse Studios, runs a professional development program called NetWorkLab. During the pandemic, as everyone did, we all went online. All of our work is highly collaborative, involving both internal and external partners, and when everything went online, we struggled with how to continue our work together, to maintain our collaborative processes in the absence of face-to-face meetings.

We certainly weren't alone in this challenge. But a few of our team members decided early on to document all the different things we were doing, all the different remote collaboration technologies and methods we were trying -- what worked and what didn't -- with the idea that the lockdowns might last a long time and that we'd need to get better at this new mode of work. And over the course of those couple of years of the pandemic, we did get better, largely because we were documenting our progress. This informal documentation became kind of an internal manual for working online.

This has turned out to have been an extremely valuable contribution to our ongoing work because we continue to be a hybrid workplace, and we continue to use and refine the tools and methods we developed and documented during the pandemic to accomplish our main tasks. Having this internal manual has been great for us. But lots of organizations, including I'm sure many of yours, struggle with hybrid collaboration.

Here we saw an opportunity. We realized that we could operationalize a byproduct of our efforts to adapt to hybrid work. With NetWorkLab (and the help of NEH) we have turned the internal documentation we developed into an external program, a curriculum and course to teach other faculty members, librarians, museum professionals, and others in the cultural sphere to work more effectively with their colleagues and stakeholders in the online environment. NetWorkLab, once a byproduct, has become one of our core products

Good Habit 2: Cultivate subcultures. Keep your organization weird.

Innovation doesn't usually come from the mainstream, from the established. The established are usually too busy protecting their position to innovate. And why should they? They're doing just fine with the things they're doing.

Rather, innovation comes from the fringes, and you should cultivate the fringes of your organization, your business, your communities.

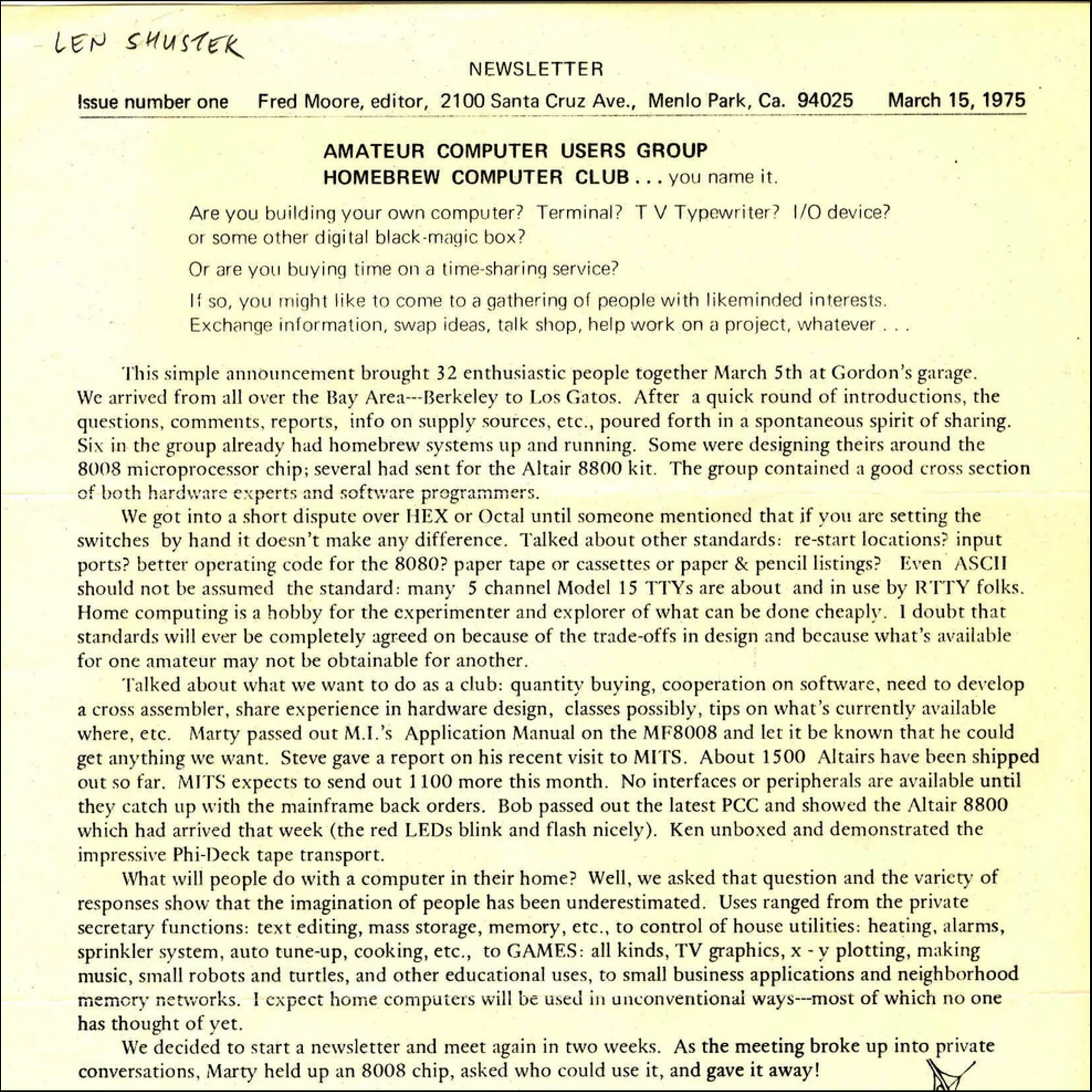

In the mid-1970s, there emerged on the fringes of the San Francisco Bay Area computer science establishment -- at well-established companies like Xerox and Hewlett Packard and in the computer engineering departments of Berkeley and Stanford -- a group of enthusiast engineers, who were tinkering with building small computers in their garages and basements.

At the time, computing was not like we know it today. The earliest computers, which grew out of the World War II military-industrial complex, were enormous machines called mainframes. But the central characteristic of the mainframe wasn't its size, but its computing architecture, which was highly centralized. Users of mainframes didn't have access to computing resources, the guts, of the machine. Mainframes were hard coded by the engineers that built them for pre-defined purposes. They were not multi-purpose machines like the ones we all use today. Users couldn't program them for new tasks or install new applications. A human resources mainframe couldn't be used to play games. An inventory system couldn't be used for word processing. If a user wanted to alter their purposes, they either got a new mainframe or sent it back to the company for the engineers to hard code the new functionality.

Some of those engineers, however, had a different vision for computing. These folks wanted a computer at home that they could use for a range of purposes, from balancing their checkbook, to writing letters, to tracking their weight, to playing games -- and they had the skills to build them. By March of 1975, there were enough of these folks building what came to be known as "personal computers" in the garages and basements of the Bay Area to found a club that would become known as the "Homebrew Computer Club."

Keep in mind that the idea that someone might own their own computer was completely outside the mainstream at the time. Computers were heavy equipment that the military, government agencies, and big businesses used to do things like track ordinance, tally the census, and manage employee hours and payrolls. A computer wasn't something any ordinary person would think to have at home. Indeed, in 1977, Ken Olsen, the CEO of Digital Equipment Corporation, probably the second largest computer company in the world said just that (although there is some debate about the context in which the remark was delivered): "There is no reason for any individual to have a computer in his home."

This was the same year that one of the new "personal computers" that emerged from the Homebrew Computer Club membership was released for sale: The Apple II. Within 10 years, personal computing had become the dominant model of computing.

The lesson here is that the mainstream of a field can't always see where that field is heading. In the late-1970s, the personal computing culture of just 10 years later was virtually unimaginable to the leaders of the world's largest computer companies. But on the fringes of those companies, in the garages and basements of some of their junior engineers, the future had already arrived. The Homebrew Computer Club was a subculture that the mainstream would have done well to cultivate instead of dismissing. Today Apple is the largest company in the world, and Digital Equipment Corporation is long gone.

An example from my own work is what we call "the Treehouse."

The Treehouse is a weekly career and life skills workshop organized by and for students in my lab. A few years ago, what had been a periodic work progress meeting morphed, under the urging of the students themselves (but with support of Greenhouse Studios leadership), into a weekly professional development series with students taking turns presenting skills they had learned, projects they done, and cool ideas they had come across.

Gradually, the informal lunch meeting became a more formal series of training workshops. As Treehouse thrived, we gave it increasing amounts of support: paid time for the students away from regular duties to participate and prepare, space in the lab, the occasional food delivery.

By supporting a subculture within the organization (and under the leadership of my colleague, Brooke Gemmell), we were able to cultivate a new line of work, keeping that business in-house rather than forcing it outside like Ken Olsen did. Our life design work is now among the most exciting things we do.

Healthy Habit 3: Explore the "adjacent possible." Borrow from other domains.

I take this term, "adjacent possible," from Stephen Johnson. What Johnson means by the adjacent possible are the opportunities that are just outside the circle of things that draw your immediate attention, the things that are just one step removed from what you normally do and think about. Some good ideas are in your immediate view, but most good ideas are just outside it -- in the places, people, disciplines, fields, books, and media that are close to what you do, but not exactly what you do.

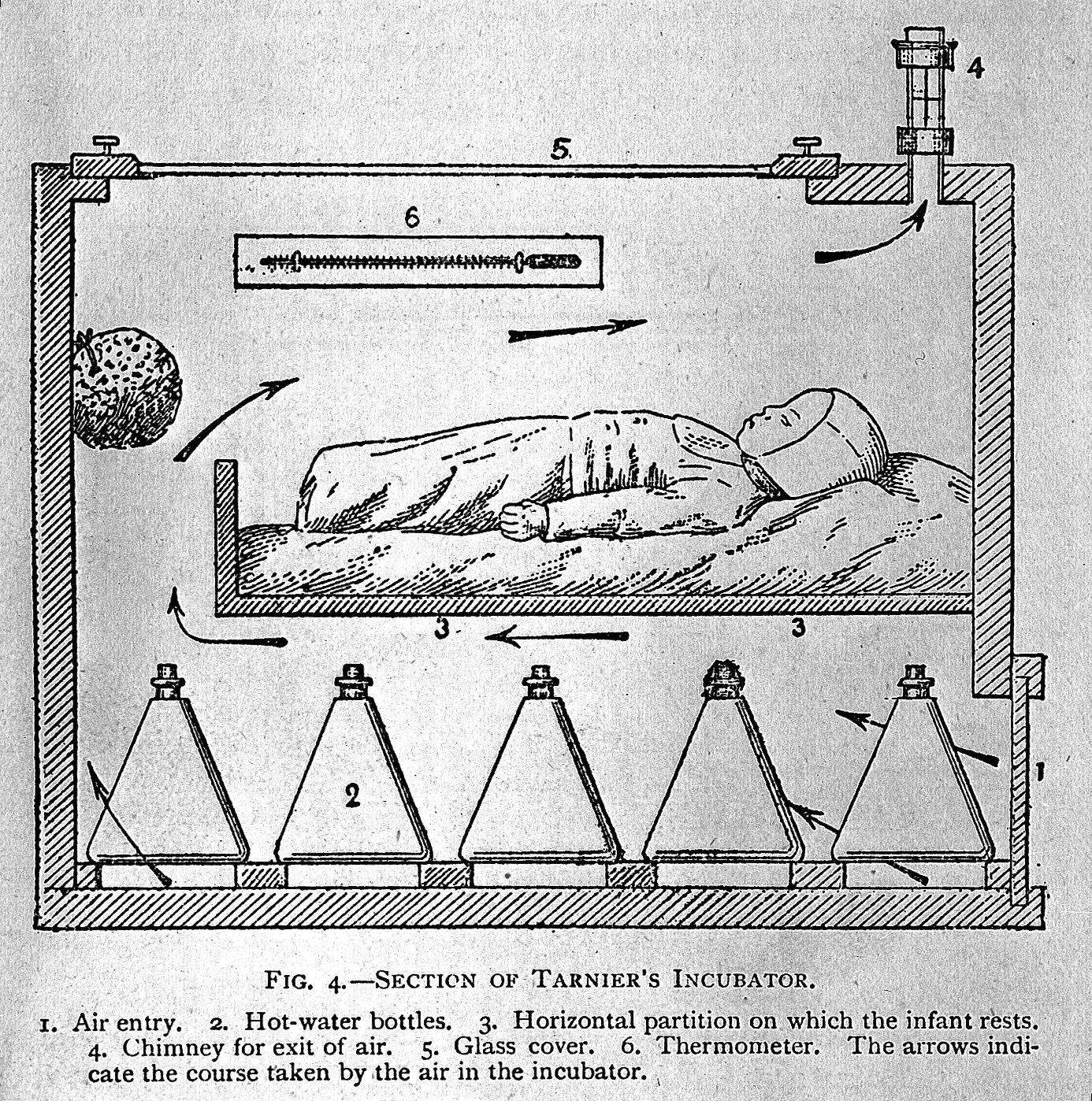

In his book, "Where Good Ideas Come From," Johnson gives the example of the French physician, Etienne Tarnier, who lived in the mid-19th century. Tarnier was an obstetrician, who worked in the children’s hospital in Paris. As an obstetrician, Tarnier was confronted daily by the painful reality of infant mortality. During the 19th century fully one in five Parisian babies died in infancy at a time when Paris was the wealthiest, most sophisticated city in the world.

And it was a stubborn problem. Doctors knew that death rates were higher among babies born premature or with a communicable disease, and they knew that one of the keys to keeping those children alive was temperature regulation. But in a world without central heat or air conditioning, temperature regulation was no simple matter. That was especially true in a city built of stone like Paris, where winters were wet and cold and summers stiflingly hot.

In addition to being a physician, Tarnier was an animal enthusiast, and visited the Paris Zoo regularly. Indeed, it's not surprising that a physician whose primary interest was human biology would be interested in animal biology. One day, Tarnier was vising the zoo and happened to come across a zookeeper lecturing at the chicken hatchery. The zookeeper explained how they used an incubator to keep the chicken eggs at the right temperature so that the eggs would hatch normally and on time. Tarnier pulled the zookeeper aside and asked, "What if the eggs were babies?"

Tarnier and zookeeper got to work scaling up the incubator to fit a baby. It was little more than a box with a hot water bottles mounted underneath, some air circulation, and a thermometer--but it worked. Within a few years, the infant mortality rate in Paris had dropped from 1 in 5 to 1 in 20. Along with vaccines, antibiotics, and anesthesia, Tarnier's incubator is one of the greatest medical breakthroughs of all time.

Tarnier's breakthrough didn't come from the center of his medical practice. It didn't come from the study of human biology or medicine. It came from the related study of zoology, from veterinary science. That is, it came from the adjacent possible.

An example of the adjacent possible from my own work is an application my colleagues and I are building called Sourcery.

Sourcery's origin story begins more than 20 years ago in my grad student apartment in Washington, DC. In the years prior to moving to Washington, I had been studying for my Ph.D. in Oxford. Recently married, my wife Anne and I had moved to England for me to finish my studies on the agreement that when I was finished with the coursework, I'd follow her back to the U.S. so she could attend law school and finish the dissertation there. She got into Georgetown, and we moved to DC in 2001.

One day, I was sitting alone at the kitchen table working through the notes I had taken on some documents at the British Library ... and I couldn't read my handwriting. I needed another look at the document, but I had no way to get it. Camera phones were just starting to be a thing, and I thought, "I wish I could just pay some grad student to fetch the document, take a picture, and email it to me in Washington." I knew from experience that there had to be a dozen fellow grad students sitting in the British Library at that very moment who would be happy to make a few quid. Alas, I had no way to know who they were or how to contact them, and I just gave up on that piece of the research.

A few years later, I was out to dinner with a friend who was visiting from New York. At the end of the meal, I offered him a ride back to his hotel, and he said, "let me see if I can Uber." I had no idea what he meant. He explained that Uber was a new "ridesharing" service that was operating in New York. Uber connected people who had access to a car with people who needed a ride via a smartphone application equipped with geolocation services. I thought: "Here's the solution to my British Library problem."

It wasn't until the travel and social distancing challenges presented by the pandemic that I actually got around to starting work on the idea, but what we now call Sourcery is essentially "Uber for archives." Just as Uber connects people with access to a car to people who need a ride, Sourcery connects people with access to an archive with people who need a document at that archive. A user places a request for a document through the Sourcery app. Sourcery finds another user nearby the archive where the document is held and this "Sourcerer" fetches the document, takes a picture, and sends it along in return for a modest fee.

I didn't get this idea from the field of history. I didn't get it from the field of library science. I didn't even get it from the field of digital humanities. I got it from the smartphone-based ridesharing business. I got it from the adjacent possible.

OK. We're running out of time, and I want to be sure to have room for questions, so I'm going to go quickly through three unhealthy habits, three things you should avoid, three things that stifle innovation, three things that when they come out of your mouth or that of someone around you, you should stop yourself right in your tracks.

Bad Habit 1: "We already do that."

Too often, especially in organizations, when someone posits a new idea, the knee-jerk reaction of colleagues is, "we already do that." Or "that already exists." "Or "that's not really new." As someone with ideas, you hear it all the time.

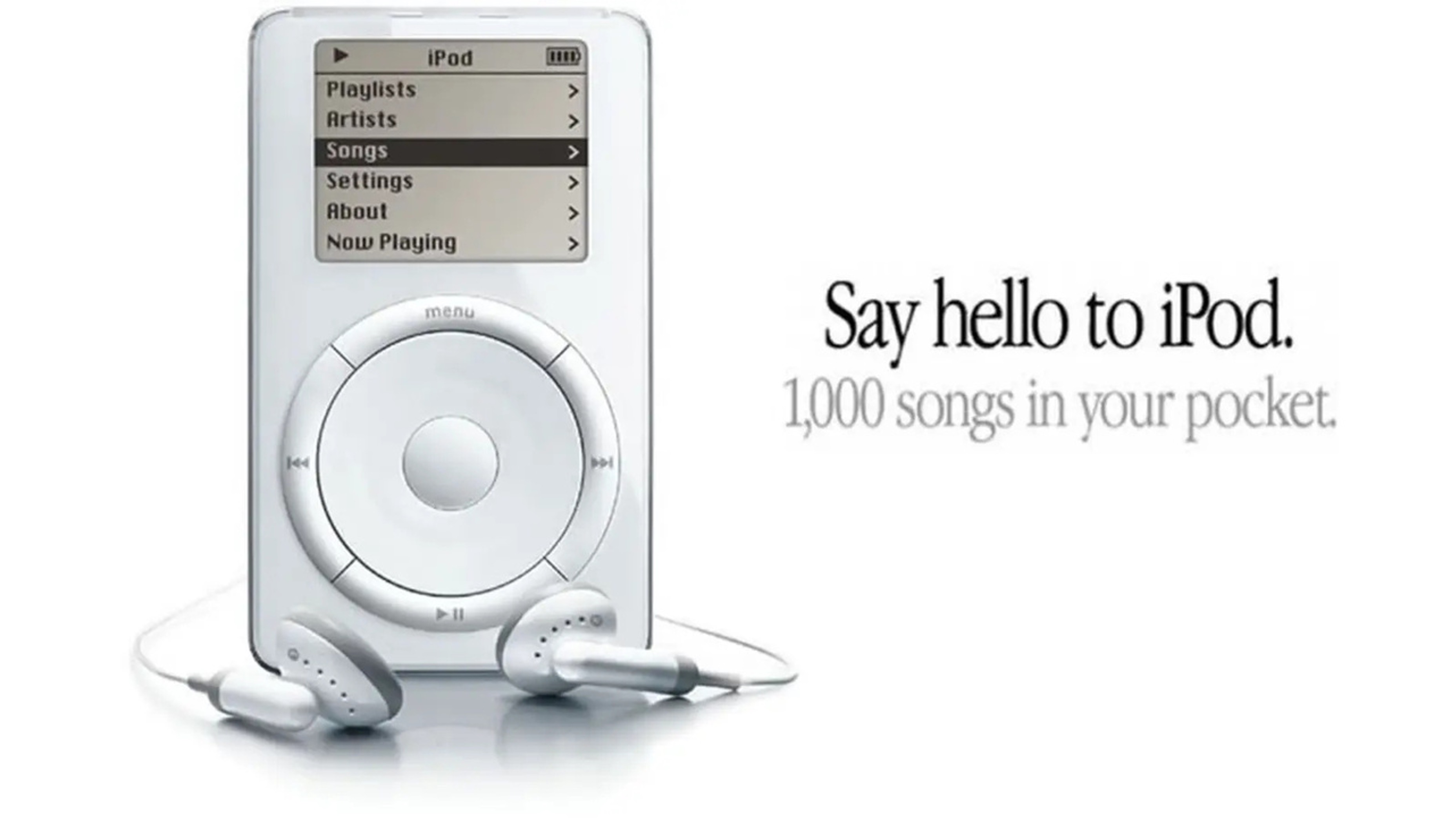

Indeed, that's what many people said when the iPod first hit the market. And it's true. When the iPod was released in late-2001, there were plenty of MP3 players already in on the market. Who on earth needed another one, especially one that cost five times as much?

The MP3 player was invented to solve a problem of its predecessor. Some of you may remember the Sony Walkman. It was an amazing device of the 1980s that allowed you to listen to your cassette tapes on the go. When cassettes were gradually replaced by CDs in the 1990s, Sony started building Walkmen that played CDs. But the CD Walkman had a serious problem. It skipped. Like crazy. It was practically useless when you were, you know, actually walking, nevermind taking a jog.

MP3 players, as solid-state storage devices with no moving parts, solved the skipping problem. You'd take a CD, move the music files to the hard drive of your computer, and then move them in turn to your MP3 player. It was essentially a solid-state Walkman.

And as a Walkman, it usually only held a single CD (maybe two or three) at a time. Partly this was a function of the cost of digital storage at the time. The Walkman cost about $50-100. At that price point, an MP3 player couldn't hold more than a couple CDs and remain a viable business proposition. But more than that, it was a mental model problem. People had become accustomed to using the Walkman and listening to one record at a time. The new technology of the MP3 player simply followed the model using a different data storage medium.

Indeed, in key respects, the iPod was simply an MP3 player. It operated the same way. You ripped your CDs onto the hard drive of your computer and moved them to the portable device for listening. People weren't crazy to say, "we already have that."

But the iPod was different in two key respects. First, it had a much, much larger hard drive. Like 100 times larger, which accounted for the $400-500 price tag. Second, it had a large screen and touch-based user interface. These two things combined to make the iPod something much more than an expensive Walkman.

The huge hard drive wasn't just a difference in degree. It was a difference in kind. All of a sudden you didn't have to listen to just one album or the few you could carry with you. You could take your entire music library wherever you went.

And the touch interface allowed you to do much more than listen to one album at a time. You could pick and choose whatever song from whatever album you felt like listening to in the moment. You could sort and easily browse your catalog. You could make playlists based on genre or mood.

The fact of the matter is that the makers of the Walkman and MP3 players didn't "already do that." Although on the surface the iPod looked and to some extent worked like those devices, Apple was doing something altogether different, something that shifted us from the media environment of the 20th century to the media environment of the 21st century (for better and for worse).

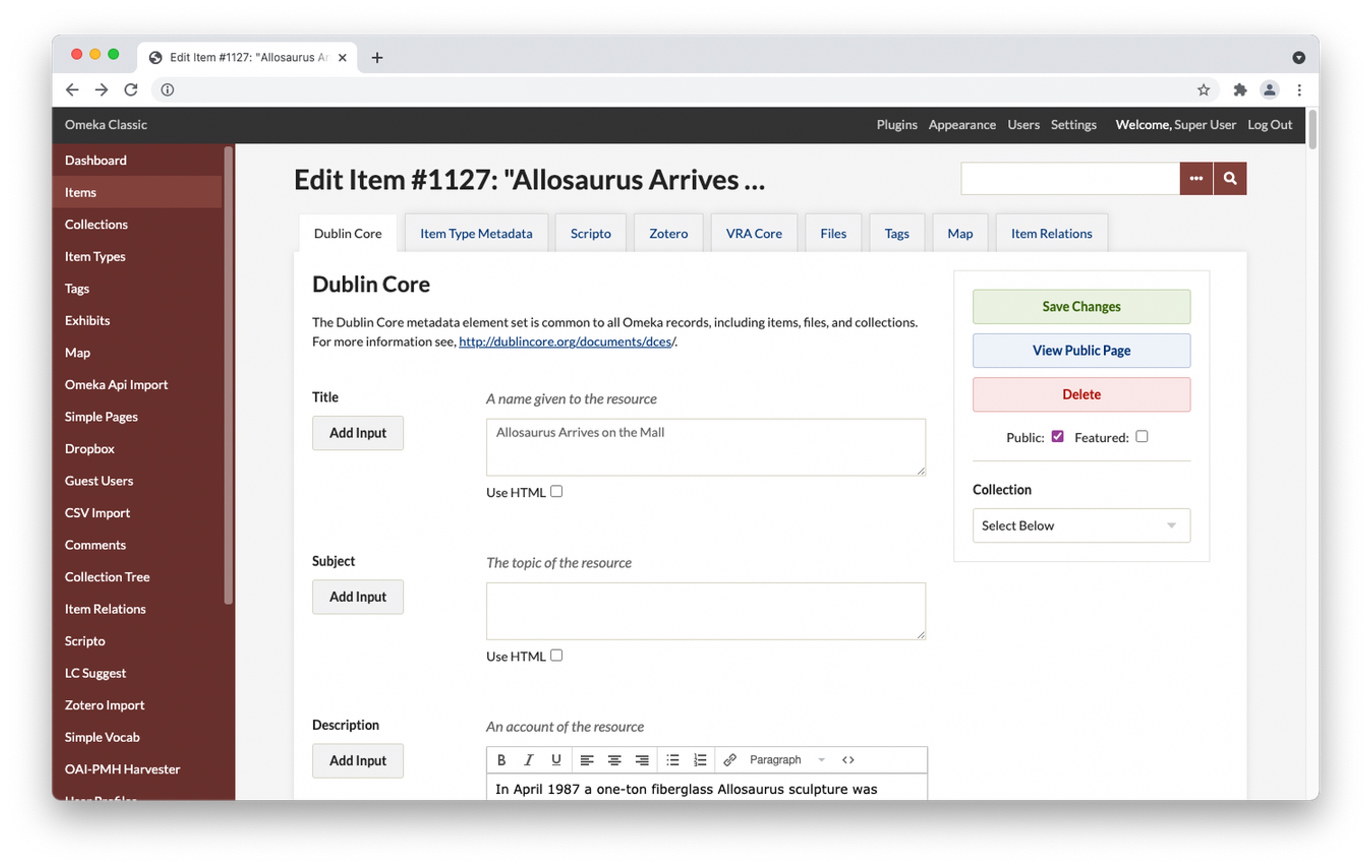

I heard something similar when my colleagues and I at George Mason University’s Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media (RRCHNM) launched our Omeka software. Omeka is a web application that allows museums and other cultural institutions to organize and present their collections online. When we launched Omeka in 2007, there were already lots of software platforms for managing digital collections, and we heard over and over again, "we already have that."

Our critics weren’t entirely off base. There did exist several digital collections management platforms at the time we released Omeka, including ContentDM, Past Perfect, and Greenstone. But what those critics didn’t see was that the existing collections management platforms were intended for the desktop, not the web. Some of them had modules (usually at additional cost) that would allow a curator to take some of the items in their database and put them on their institution’s website, but they were fundamentally engineered to work in a non-networked environment.

Omeka on the other hand was web native. It was built using the technologies of the web expressly for operation on the web. This allowed it to do things, such as mounting narratives using an Exhibit Builder, placing collection items on a Google Map, and collecting stories and images from patrons, that made it more than just an online collections database and rather a platform for online engagement with cultural heritage.

Omeka isn’t not a collections management system. But it also isn't just a collections management system. And that's the fundamental mistake people made when they first told us, “We already do that." They didn't already do that, and because the IMLS took a chance on that argument in 2007, Omeka is today used by thousands of cultural heritage institutions around the world.

Bad Habit 2: "It isn't ready yet."

Here's another thing you'll hear as a person with ideas: "It isn't ready yet." You may even tell yourself this when you're doing something new and risky. Don't listen. Too often we think something has to be finished, be perfect, before we show it to other people. This is an incredibly unhealthy habit for innovation.

An example of this is Gmail. Gmail was released in 2005 as a "beta" product, the "beta" signaling that it was still under construction. Gmail was developed by a small team of Google employees who needed a better way to manage the huge amounts of email that a start-up like Google generated, an amount of email that more traditional businesses didn't experience and the email clients they used couldn't handle.

As an in-house tool, Gmail was buggy and unpolished, but it worked in important ways. The search function in particular was far superior (and still is) to traditional email clients. The Gmail team also took a lesson from the iPod and provided users with a practically unlimited amount of online storage so they could access all of their email from anywhere at any time. These innovations were significant enough that, despite the bugs and rough edges, Google decided to do an invitation-only "beta" launch of Gmail among the company's most enthusiastic customers and users. Those early users provided the hands-on testing and feedback that Google need to squash the bugs and sand down the rough edges. When it finally released to the general public, Gmnail quickly became the dominant email platform, a status it retains today.

The lesson here, and one that became a mantra at my former home at RRCHNM, is that the perfect can be the enemy of the good. Trying to make something perfect often prohibits you from sharing something that's good enough, something that will allow you to get the stakeholder feedback you need to make it a success.

Bad Habit 3: "Show me the data."

This is a personal pet peeve of mine. Very often when you propose something new, people will ask you to prove to them, usually in numerical terms, why it is a good idea.

Sometimes that's OK. But sometimes it's not.

Data is generally good at telling you why you should do something. You can look at revenue figures, for example, and say, "this part of our business is growing, we should do more of it" or even "this part of our business is stalling, we should cut it." Data is good at making affirmative decisions.

But data is often bad at telling you why you shouldn't do something new. That's because you rarely have good data on the things you don't already do.

Let's say you make cherry candy. You probably have good data on how the cherry candy business is doing. Maybe people are buying more cherry candy. That data might tell you to make more cherry candy. Maybe the data says people are buying less cherry candy and you should kill the cherry candy product line. But nothing in that data can tell you whether you should launch a grape candy product line. You can go out and get new data, for example, by asking your cherry candy customers if they want grape candy. But even then, if they've never had grape candy--if they also don't already have data on their grape candy preferences--then the data won't tell you anything. Philosophers know that it isn't true that you can't prove a negative, but they also know that it requires a lot more work.

Data is important and can tell us a lot if we listen to it. But the data available to us contains infinite silences, and those silences, what the data doesn't say, are as rich and robust as the stories it tells. Because there is infinitely more data in the world than we can ever collect in a spreadsheet, we need to be wary of listening too much to our spreadsheets. If Steve Jobs and Steve Wozinak had listened to Ken Olsen's spreadsheets, we wouldn't have the Mac. If Jobs had listened to the market research that said nobody would pay 500 bucks for an MP3 player, we wouldn't have the iPhone. It's not that Olsen was dumb or that he was reading the spreadsheets wrong. It's just that his spreadsheets couldn't tell him the things they couldn't tell him. As Jobs himself once said, "A lot of times, people don’t know what they want until you show it to them."

Conclusion: The Importance of Connection

So, how do we meet the challenge of being innovative? What can we do to promote the healthy habits and avoid the unhealthy habits? In "Where Good Ideas Come From," Johnson draws a throughline in the many examples of creativity he presents. That throughline is "connection," and I've drawn a similar throughline today.

The healthy habits -- operationalizing byproducts for new audiences, cultivating the subcultures around us, exploring the adjacent possible --connect us with new people, places, ideas, domains and networks. The unhealthy habits, on the other hand -- telling ourselves and others that "we already do that," "it's not ready yet," and "show me the data" -- isolate us, close off connections, close off pathways to new information. The more connections you can make to people, places, ideas, domains and networks, the more innovative you will be.

What does it mean in practice to make connections? Here are a couple ideas.

First, explore your excess capacity. We're always thinking about the things we don't have, the things we need. I don't have enough money. I don't have enough time. Maybe that's true. But what do you have enough of? Where do you have extra? Your next project may be sitting right there.

Second, take time to tinker. Time spent screwing around with new software products, for instance, is not time wasted. Migrating your to do lists from one task manager to another task manager or from one kind of notebook to another kind of notebook is not time wasted. Writing email filters so that your email inbox looks different is not time wasted. You may feel like you're wasting time, but you're not. What you're really doing is connecting to new skills, new workflows, new problems, new opportunities.

Third, reopen closed issues, problems you think you have solved in the past that you said, I've already done that. Do it again. Do it differently. The world has changed since you solved that problem. You've changed. Maybe there's a new solution out there now that's bigger and better than the first solution you came up with. Maybe there's a new audience for that solution.

Fourth, honor your hunches. Remember the silences in spreadsheets, and know that there's a bigger spreadsheet, a larger database in the accumulated experience of your senses, in your combined experience of the world than in any Excel file you'll ever build.

Fifth, plan for serendipity. Go to the zoo. Go for a hike. Read a book that you wouldn't normally read. Watch a show you wouldn't normally watch. Go to a party you wouldn't normally go to. Connect to the adjacent possible.

Finally, don't spend time alone if you can spend time together. Cultivate your networks of family, friends, colleagues, and coworkers. Meet a stranger in a coffee shop. Whomever. We are social animals. The people around you, more than anything else, are your adjacent possible.

Thank you for having me.

Member discussion