Meet AcadiMeet; or, Adventures in Vibe Coding

Anyone who has worked with me knows that while I can talk the talk of web development, and while I do a relatively good job of managing teams of developers and designers, when it comes to walking the walk, I’m usually just crawling the crawl. So when I took up an idea for a new web application on my own last week, I had very little reason to think I would succeed. Or at least that would have been true if I had been truly going it alone. But I wasn’t going it alone. I had a partner. Its name is Claude.

This post has two purposes. First, I want to introduce you to my new project, AcadiMeet, a scheduling app, akin to Doodle and whentomeet, but designed specifically for university faculty and staff members with their particular constraints and quirks in mind.

AcadiMeet does all the things that Doodle does. You create meeting polls by selecting multiple potential dates and times. You add colleagues’ email addresses to the poll, and the system notifies them of the pending meeting invitation. Invitees respond directly through a link in the email and add their availabilities to the poll, either by creating an account (to take advantage of additional features) or by participating as a guest. The system aggregates everyone’s responses into a visual heatmap showing which times work best for the most people, and you choose a slot. Once you’ve finalized the time, AcadiMeet generates and sends calendar invitations (.ics files) to all the participants. So far, so ordinary.

But unlike Doodle, AcadiMeet takes into account the unique rhythms of academic life: the ebb and flow of the semester, the solitary demands of research and writing, the disruption of conference travel, the responsibilities of advising and committee work. It accommodates university-specific things like fixed teaching schedules, office hours, department meetings, and the idiosyncratic schedules of faculty members, who each tend to be available at very different times. First and foremost, it respects the faculty’s expectation that they control their own time and respects their privacy accordingly. For instance, AcadiMeet only displays aggregate availability: it only displays how many people are available when, not when individual invitees are available. Your name is never attached to the meeting times you select or don't select. AcadiMeet is also free of annoying ads, it doesn’t break on mobile under the weight of annoying popups, it won’t ever sell your data, and it’s completely free. (At some point, if it gets super popular and I can’t maintain the infrastructure out of my own paycheck, I may start charging a $5 or $10 lifetime use fee to people who want to create their own polls. But anybody who signs up in this launch period will have free lifetime access.)

Aside from my commitments to free software, the main reason I’m not charging anything for AcadiMeet is because my reason for building it wasn’t to make money. I don’t even have a particular interest in productivity applications (although I have been talking about the need for a better scheduling app for a long time). I built it to see what a technically literate amateur (but by no means proficient programmer) could accomplish in their spare time in a week with the help of AI.

This is the second purpose of this blog post: to record my process of working with Claude to vibe code this app (including both the technical details but also the collaborative strategy and workflow), and to reflect on what this may mean for the future of digital humanities and web development in general.

The process was revelatory. Over the course of about six days, working in sessions of two to four hours (usually early in the nothing or at night after my kids went to bed), Claude and I built a full-stack web application from scratch. We used React for the frontend, Node.js and Express for the backend, Prisma as an ORM, and SQLite for the database. We integrated SendGrid for email notifications. We implemented secure authentication with password reset flows. We added features like guest responses (no login required), automatic data cleanup for privacy compliance, calendar invite generation, and a visual availability heatmap. We hardened the application with security measures like rate limiting, CORS configuration, and secure session management. We optimized database performance with strategic indexes. And we deployed the whole thing to Railway with a custom domain from Reclaim Hosting and DNS management from Cloudshare.

I couldn’t have done any of this alone. I’ve tried before. I have half-finished apps projects littering my hard drive, each representing an evening or weekend when I thought “this time will be different.” What made this time different was that Claude served as something more than a code generator or a very sophisticated Stack Overflow. Claude was a thought partner, a patient teacher, a tireless debugger, and—most importantly—a collaborator who could hold the entire architecture of the application in its context window while I could barely remember whether I’d put the API configuration in config.js or utils.js.

The process looked like this: I would describe what I wanted—often in fairly vague terms like “I need users to be able to set up their teaching schedule” or “guests should be able to respond without creating an account”—and Claude would not only write the code but explain the architectural decisions, suggest best practices, anticipate edge cases I hadn’t considered, and walk me through implementation step by step. When I hit bugs (and I hit many), I would paste error messages and Claude would diagnose the problem, often catching issues in files I hadn’t even been looking at. When we deployed to production and encountered CORS errors, DNS propagation delays, and SSL provisioning issues, Claude calmly walked me through troubleshooting each one.

But here’s what strikes me as most significant: this wasn’t about Claude doing all the work while I watched. I was making real decisions about features, user experience, and data models. I was reading and understanding the code. I was learning about security best practices, database optimization, and production deployment. The difference is that instead of spending 80% of my time stuck on syntax errors, missing imports, and cryptic documentation, I could spend that time thinking about what I actually wanted to build and why. Claude handled the mechanics; I handled the vision and the domain expertise.

This has profound implications for digital humanities, particularly for those long-running debates about “hack versus yack” and “big tent DH.” For years, we’ve argued about whether digital humanities requires technical skills—whether you need to be able to code to be a “real” digital humanist, or whether critical reflection on digital methods counts just as much. We’ve wrestled with the tensions between builders and theorists, between people who make things and people who think about things. The “big tent” was supposed to resolve this by saying there’s room for everyone, but in practice, the tent often felt like it had a VIP section for people who could—whether because they had the knowledge, the luxury of a reduced teaching load, the grant funds, or the institutional support—actually deploy a Rails app. What I experienced with Claude suggests we may be entering an era where this distinction becomes less meaningful—where a historian who deeply understands the research problem can collaborate with an AI to build sophisticated tools without needing to become a professional developer first. The hack/yack binary starts to collapse when the “yack” people can suddenly “hack” too, not by learning to be programmers, but by being able to articulate clearly what they want to build and why. The question may no longer be whether you can code, but whether you can think critically about what should be coded and how it should work.

I want to be careful not to overstate this. I’m not a complete novice—I’ve been involved in web development for nearly 30 years. I understand databases and APIs and I know my way around a text editor and the command line, even if I can’t always write the code myself. Someone with no technical background at all would have a steeper learning curve. And there were definitely moments where my existing knowledge was crucial: knowing to check the browser console for errors, understanding what a SSL certificate is, recognizing when a problem was DNS propagation versus a code issue. This isn’t magic, and it isn’t replacing the need for technical literacy. But it is dramatically lowering the barrier between technical literacy and technical proficiency.

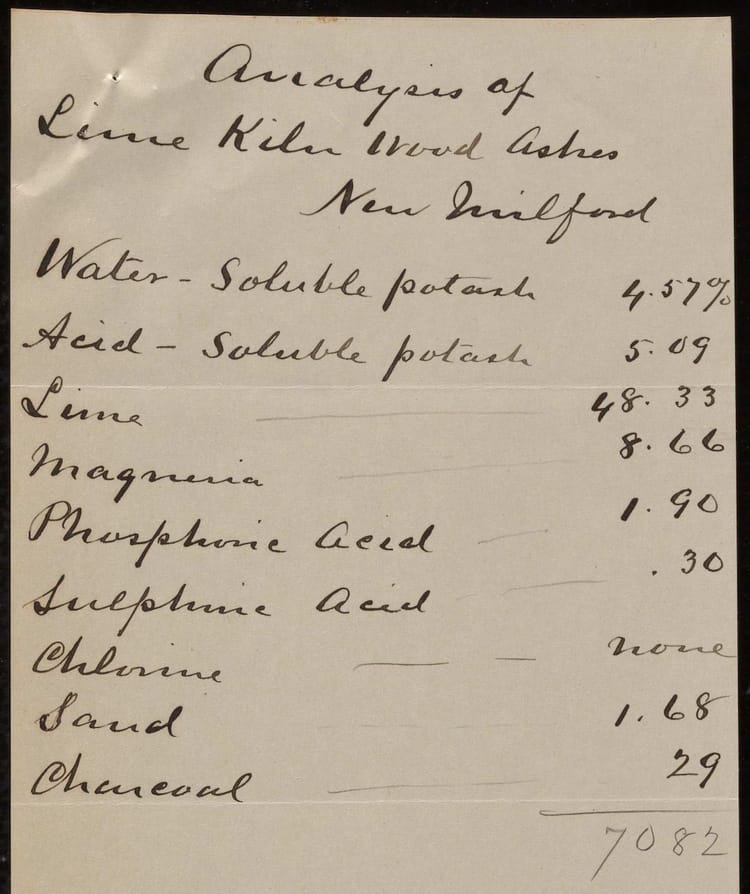

It’s also worth reflecting on what this means for the practice of digital humanities itself. If we can build custom tools this quickly, do we still need to rely so heavily on platforms and tools built by others? If a medievalist can spend a week with Claude building a specialized manuscript transcription interface, or a social historian can create a custom network visualization tool tailored to their specific data, what does that do to the DH ecosystem? Do we end up with more bespoke tools and fewer shared platforms? Is that good or bad? I don’t know the answer, but I think we’re about to find out.

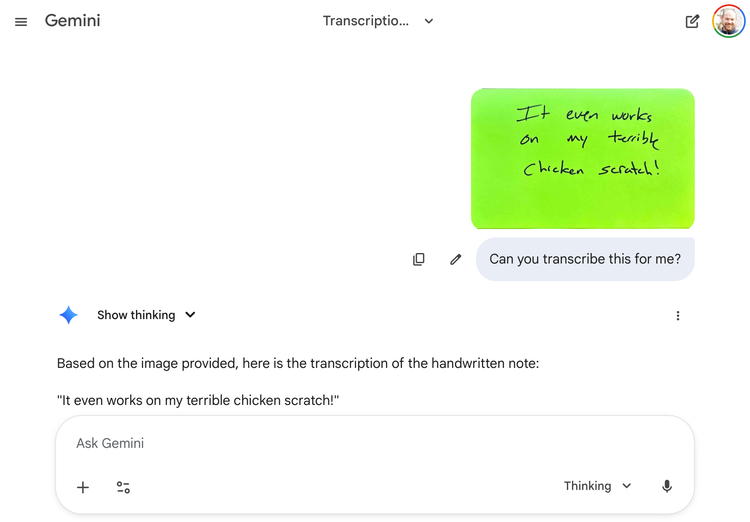

Because we are so grounded in the textual, I think a lot of humanists miss a crucial point: these large language models are not just essay-generating machines; they are making machines. If your experience is limited to watching an AI's ability to write prose, you might feel alternately impressed, underwhelmed, or threatened by what it means for the future of the humanities. But if you reorient your perspective and start thinking about AI as a collaborator that can help you do the parts of your work that aren't writing (after all, as an English or history professor, you're likely a damn good writer already), you start seeing its potential differently. I encourage colleagues, especially the skeptics, to take a spare afternoon to work with one of these systems on a project adjacent or preliminary to your main research—perhaps organizing a Zotero library, building a custom research workflow, or visualizing some long-dormant data from your dissertation. You may not be convinced that these tools are “good,” either in the practical or moral sense (I’m not), but you will certainly see them differently.

For now, I’m just thrilled that AcadiMeet exists, that it works, and that it might actually make my colleagues’ lives a little bit easier. I encourage you to try it out and use it to schedule your next meeting! And I’m excited—maybe a little anxious—about what comes next. Because if I could build this in a week, what else is possible?

Member discussion