Seeing Old Science

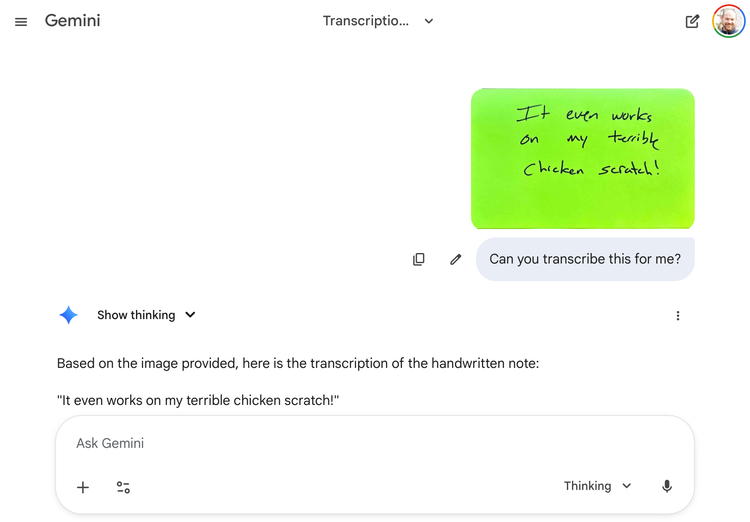

AI’s writing ability has gotten all the attention in campus discussions. But AI’s ability to see is just as big a deal. In my series on vibe coding, for example, I noted that AI’s killer feature is its ability to see what’s on your screen (via a screenshot or direct browser access through something like Google Antigravity) and give you step-by-step instructions on what to do next. Likewise, Gemini’s new ability to see what’s happening in a handwritten archival document and accurately transcribe it is a game changer for historical research.

But this new ability to see archives isn’t just something of note to humanists. It may turn out to be even more important for the sciences.

The Extension Service Problem

For years, I have been trying to get a project off the ground on land-grant college agricultural extension records and climate science. The basic insight was this: for nearly 100 years, UConn’s Agricultural Extension program (the oldest in the nation) and similar services at other land-grant universities across the United States have sent agents to collect data from individual farmers on topics like crop yields, seed prices, weather events, water resources, livestock diseases, planting and harvesting schedules, and farming techniques.

Currently accessible only with a visit to the archives, these records likely contain historical environmental data of significant interest to contemporary scientists. Specifically, these records may provide localized and microclimate data that is missing from other sources. The frequency and coverage of extension agent data collection, which focuses seasonally on individual farms, is significantly more granular than that of other sources, which typically collect at the level of the county, region, or weather station, sometimes at infrequent intervals. The USDA National Census of Agriculture, for example, is collected only every five years. Thus, the data hiding in the archives of the nation’s extension services may provide a higher resolution (though perhaps lower signal) complement to the lower resolution (though perhaps higher signal) data available from other sources.

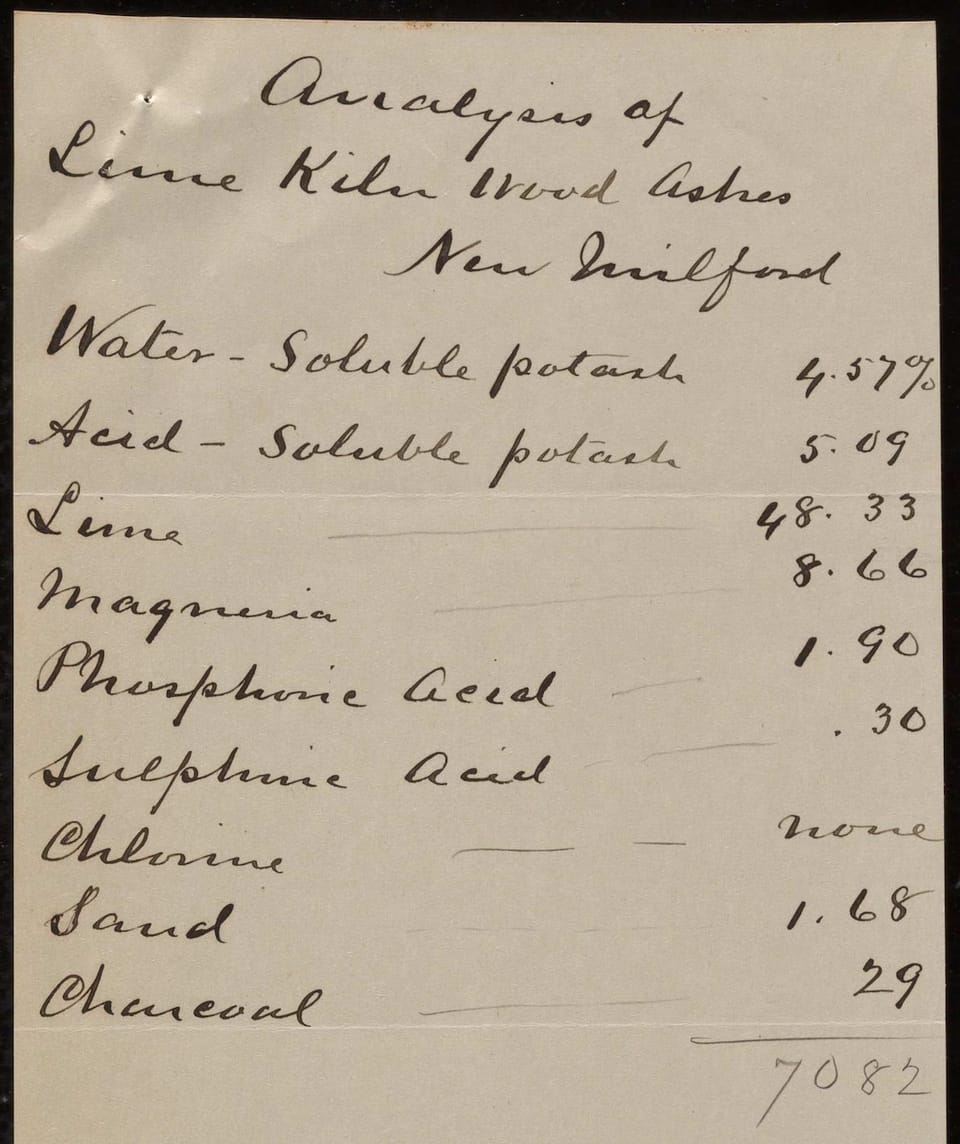

The problem has always been extraction. This data remains buried in the unscanned, narrative, and often handwritten reports of field agents and similar documents like farmers’ diaries. Transforming these records into usable data would require not just transcription but a sophisticated understanding of the nature of the collections and the development and implementation of new methods of extraction and dissemination.

In a pre-AI world, this seemed infeasible, and funders told me so. It was way too complicated and labor-intensive to make sense as a grant-funded project. The ROI just wasn’t there. You’d need armies of graduate students and paleographers spending years squinting at faded handwriting, trying to distinguish between a 3 and an 8 in a yield column, or figuring out whether that marginal note about a late frost was in May or March.

But now, in a new age of machine handwriting recognition that can read handwritten tabular data and unstructured field notes, this project seems eminently doable. (Note: I’m already in contact with some funders about the idea, so if you’re at a flagship land-grant institution with an agricultural extension program and would like to work together, please reach out and let me know.)

Beyond Agricultural Extension

There are lots of other possibilities. What about mining scientists’ lab notebooks for failed experiments that could in fact be promising given 50 or 100 years of technological and scientific advancement? How many abandoned lines of inquiry are sitting in boxes in university archives simply because the technology or the theoretical framework wasn’t available in 1923 or 1967 to make sense of what a researcher was seeing?

What about old rejected grant proposals? The National Science Foundation and NIH have been funding research for decades, and their archives contain not just successful proposals but all the rejected ones—including the ones rejected not because they were bad science, but because they were too expensive, or too speculative, or addressing problems that seemed intractable at the time. With AI-assisted archival access, we could systematically mine these proposals for ideas that might be feasible or relevant now. (Thanks to my friend, James Shulman, President of the Rockefeller Archives Center for this idea.)

The same applies to field notes from ecological surveys, meteorological observations from before the establishment of standardized weather stations, medical case files from rural hospitals, engineering test reports from abandoned infrastructure projects. The scientific archive is vast, and most of it is inaccessible not because it’s been lost but because reading it at scale has been impossible.

This isn’t just about efficiency—though the efficiency gains are real and important. It’s about what becomes thinkable when the constraints change.

In the world of extension service records, for instance, we could start asking questions about the relationship between specific farming practices and local climate variation at a temporal and spatial resolution that’s never been available before. We could trace the adoption and abandonment of particular seed varieties across different microclimates. We could see how individual farmers responded to specific weather events in ways that aggregate data simply can’t capture.

More broadly, AI’s ability to see and comprehend handwritten archival documents means that scientific knowledge that exists only in analog form—and there’s vastly more of this than most people realize—can suddenly become part of the active research infrastructure. The past becomes computationally accessible in a way it’s never been before.

This has implications for how we think about scientific reproducibility and cumulative knowledge. If experiments from the 1930s can be digitally accessed and their data extracted at scale, we can start to ask whether findings that have been cited for decades are actually reproducible when you look at the original data. We can identify patterns across studies that individual researchers might not have noticed. We can build meta-datasets that span not just recent digital research but the entire archival record.

Challenges and Opportunities

There are, of course, complications. The same concerns about AI as an intermediary between researchers and primary sources that apply to historical research apply here too, perhaps with even higher stakes when we’re talking about scientific data that might inform policy or public health decisions.

There are questions about data quality and interpretation. Extension agents weren’t trained as climate scientists, and their observational methods weren’t standardized in the ways we’d expect today. Extracting usable data from these records will require not just transcription but careful validation, contextualization, and uncertainty quantification. AI can read the handwriting, but it can’t automatically tell you whether a particular measurement is trustworthy or how to weight it against other sources.

There are also questions about labor and expertise. The graduate students and archivists who would have done this work by hand aren’t going to be replaced by AI, but their roles will change in ways we need to think carefully about. What new kinds of expertise do we need? What happens to the deep, slow knowledge that comes from spending months immersed in a particular collection?

And there are questions about access and control. If AI-assisted archival access makes large-scale data extraction feasible, who gets to do it? Who decides which collections get digitized and analyzed? How do we make sure the expertise of archivists, who often have spent decades stewarding these collections is retained as a meaningful part of the process? How do we ensure that this capability serves public research rather than being captured by private interests?

We’re at a moment when what’s possible in scientific research using historical records has fundamentally expanded. The institutions that fund and support science—NSF, NIH, IMLS, NEH and private foundations like Mellon, Sloan, and Schmidt—should take note. Projects that engage the sources and expertise of the humanities that seemed infeasible or too expensive may suddenly be not just doable but essential. The scientific value locked in historical records has always been there, but the cost of extraction made it inaccessible. That constraint is rapidly disappearing.

This means revisiting assumptions about what kinds of research are worth funding, about the relationship between archives and active research, about the role of humanists and archivists in scientific discovery. It means thinking differently about digitization priorities and archival infrastructure.

And it means that scientists need to start thinking more seriously about historical records as research resources. Not just as background or context, but as sources of actual data. The barrier between historical research and contemporary science is becoming more permeable, and that’s going to create opportunities that we’re only beginning to imagine.

The extension service records I’ve been thinking about for years are just one example. There are hundreds of similar collections, in every scientific field, waiting to be opened.

Member discussion