Writing the History of the Future with Google Gemini

With the end of the semester, I have been experimenting with Google Gemini 2.5 Pro (preview) to see how it works with different things on my to-do list. I've used it to outline a 12-month writing schedule for the book project I'm starting (excellent). I've used it to suggest syllabus revisions for the writing course I taught this semester based on my students' teaching evaluations (revealing). I've used it to help produce a short abstract of a long blog post (tremendously time saving). I've used it to generate a new street map of my neighborhood that would redirect the flow of traffic in safer ways (terrible). I've used it to compare the text of a draft grant proposal with the proposal guidelines to make sure I've covered all my bases (fantastically useful).

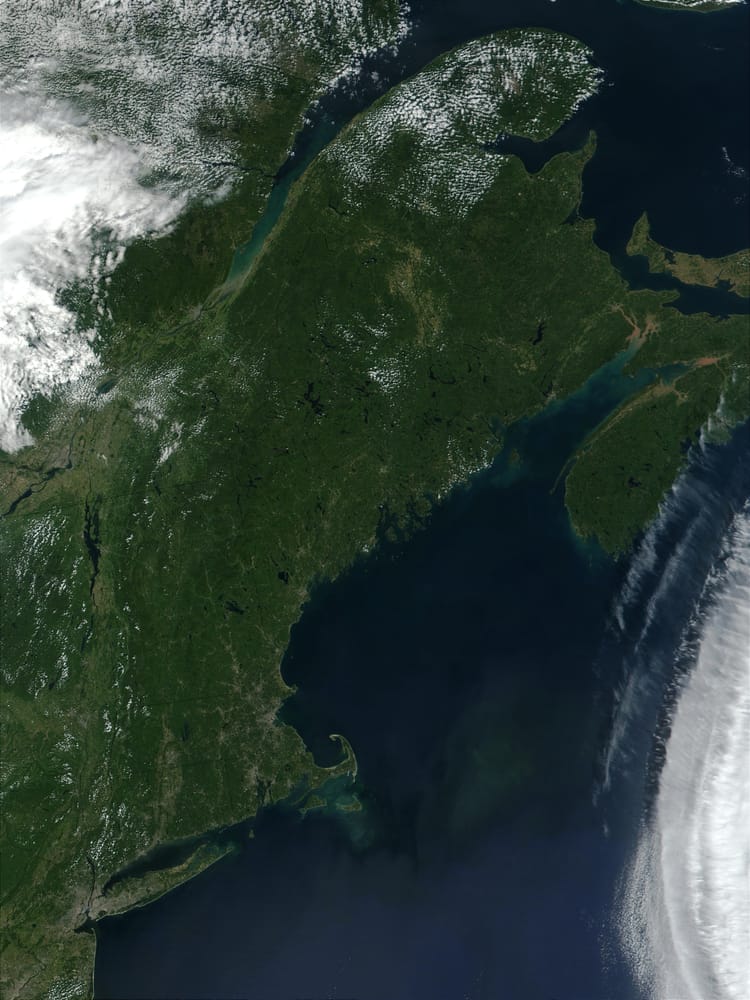

This morning, I thought I'd give Gemini a more creative task. I asked the assistant to help me create a history of the future based on the call for greater regionalism I made in January on this blog in a post entitled, The New England Option. I supplied the basic thrust of the narrative, the periodization, the geography, the naming conventions, and the major plot points. I also provided the precipitating political events that premise the narrative. I then worked through several iterations of the story Gemini produced to add detail and complexity, build structure, and correct errors.

I can't say it's great literature or great history. I don't expect any of it to actually happen. And if it did happen, I expect the outcome would be a lot darker than what is described below. But as an exercise in thinking about historical contingency and in writing speculative history, it was fun.

Here is that story, imagined as an excerpt from Katja Persdotter, The American Experiment Recast: A History of the 21st and 22nd Centuries (Knopf, 2192).

Chapter 4: The Great American Rebalancing: From Federal Union to Regional Federation

The story of the United States from the early 21st century into the dawn of the 22nd is one of profound, often tumultuous, transformation. What began as a federal republic of ostensibly equal states evolved through successive waves of regional assertion, state fragmentation, territorial secession, and ultimately, a fundamental redefinition of the Union itself. This chapter traces that arc, from the nascent regional responses to federal dysfunction in the late 2020s to the establishment of a reformed United States of America in 2120.

Part I: The Spark – Gathering Storms and the Rise of the New England Compact (2027-2040)

The initial catalysts for significant regional divergence arose from a confluence of federal policy shifts and national challenges between 2027 and 2040. An administration focused on deep domestic spending cuts first targeted federal funding for university research and development, slashing budgets for key agencies and drastically reducing reimbursement for Facilities and Administrative (F&A) costs critical to university infrastructure. This blow to the innovation economy was compounded by contentious federal tax policies. The continuation, and in some years deepening, of a cap on the State and Local Tax (SALT) deduction ignited widespread anger, particularly in the affluent and middle-class suburbs of higher-tax states in the Northeast and on the Pacific Coast. These communities felt the financial squeeze of the SALT cap most acutely, viewing it as a direct assault on their household finances and their states' ability to fund essential local services. Protests, therefore, often originated in these suburban enclaves, taking the form of packed and confrontational town hall meetings, local government resolutions of defiance, and highly visible "tax fairness" rallies. Leaders in these regions argued vehemently that the SALT cap was a politically motivated measure. This impasse fueled a growing sentiment in the affected states that their fiscal models were under attack and that greater regional autonomy was needed.

Compounding these fiscal grievances was a deepening crisis of confidence in the federal government's handling of climate change, particularly regarding disaster relief. As climate impacts intensified, the Southeast was battered by super-hurricanes, leading to massive federal aid disbursements. However, states in the Northeast and on the Pacific Coast, facing their own escalating climate threats, perceived a stark inequity and believed federal aid was often influenced by political considerations or outdated formulas. This fed a powerful narrative of federal neglect, further convincing regional leaders that they needed to seize control of their own environmental and fiscal destinies.

In response to the research funding cuts, concerned university presidents and academic leaders from New England, particularly those from smaller institutions heavily reliant on federal monies, began convening in the early 2030s. These meetings, initially focused on shared vulnerabilities, gradually expanded. Fueled by press coverage and a growing sense of common cause, this group formalized into the Northeast Consortium, eventually attracting most higher education institutions across New England, New York, and New Jersey, as well as several research-oriented businesses. As the Consortium grew, its discussions broadened from solely research funding to include strategies for addressing regional fiscal equity and the need for broader political action, influenced by dialogues with influential regional political figures and diverse advocacy groups concerned about climate policy and federal spending priorities.

Independently, calls for more radical fiscal measures began to emerge from various quarters, including frustrated taxpayer advocates in suburban areas hit hard by the SALT cap, who started to suggest withholding federal tax payments as leverage.

These disparate streams of discontent converged at the Hartford Convention of 2035. Convened by leaders of the Northeast Consortium and allied state officials and regional advocates, the Convention forged a bipartisan regional interest alliance. The "Hartford Resolution" emerged, proposing that member states place a portion of federally-bound income tax revenues into an escrow account, conditional upon the restoration of research funding, full reinstatement of the SALT deduction, and a more equitable federal approach to climate change.

This bold move was institutionalized with the formation of the New England Compact (NEC) by 2040, a statutory sub-federal union initially comprising the six New England states along with New York and New Jersey. The NEC established a unified congressional caucus, a governing council, and began to coordinate on a range of policies. The unlikely cross-party and cross-ideological support for the tax withholding strategy—uniting academic and climate action proponents with fiscal conservatives and states' rights advocates—gave the NEC a powerful internal mandate. The federal government reacted with accusations of unconstitutional overreach.

Part II: The First Wave – Coastal Assertiveness and the Pacific Accord (The 2040s)

The NEC's defiance during the 2040s served as both an inspiration and a catalyst for other regions. On the West Coast, a parallel movement for regional autonomy began to coalesce. Federal tariffs on Chinese imports, stemming from earlier administrations and largely continued, were severely impacting operations at major ports like Los Angeles. Port authorities and West Coast economic leaders, witnessing the decline in Pacific trade and the hardship it caused for workers, became increasingly vocal.

Frustrated by the lack of federal response, these leaders began threatening non-compliance with U.S. Customs in the collection of certain federal tariffs, arguing they were economically ruinous. This stance found strong support among dock workers, truckers, and logistics personnel. This port-centric movement quickly found common cause with other protest movements within California: right-leaning taxpayer groups incensed by the SALT cap and left-leaning activists alarmed by cuts to research funding and federal inaction on climate change.

Inspired by the New England Compact's example, these diverse Californian factions coalesced. This growing movement spearheaded the initiative to form a broader regional alliance. Thus, by the mid-2040s, the Pacific Accord was formally established, initially led by California and soon joined by Oregon, Washington, and Hawaii. This new bloc, like the NEC, began to act as a unified force.

A defining characteristic of these early coastal compacts—the NEC and the Pacific Accord—was their pragmatic, "region-first" operational strategy. Their leadership understood that to maximize regional benefit, they needed to negotiate with whichever party held power in Washington. Their unified congressional delegations became known for their willingness to support or oppose federal initiatives based on direct regional impact rather than strict national party platforms.

Part III: The Great Regionalization – A Nation of Blocs and Balancers (The 2050s and 2060s)

The success and assertiveness of the coastal compacts during the 2050s and 2060s spurred a broader "Great Regionalization." This era produced a complex geopolitical landscape of large, formal compacts alongside a significant number of strategically independent "balancer" states. While much of this realignment occurred through political negotiation, this period was not without its undercurrents of tension. The consolidation of compact power and the sometimes-ambivalent position of non-aligned states occasionally led to localized urban protests in cities wary of dominant regional trends, and minor flare-ups involving localist or anti-compact militias in areas feeling marginalized or fearing loss of identity within the newly forming power blocs.

The major formal compacts that solidified during this period were:

- The New England Compact (NEC) and the Pacific Accord.

- The Great Lakes Alliance (GLA): Uniting Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Illinois.

- The Intermountain Pact: Formed by Colorado, Utah, Arizona, Nevada, Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, and New Mexico.

- The Southern States Alliance (SSA): A bloc including South Carolina, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana.

- Greater Texas: Dominated by Texas, with Oklahoma and Arkansas as close partners.

- The Plains Federation: Kansas, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Iowa.

Beyond these formal compacts, a substantial group of influential states opted for strategic independence. Among the most important of these were Pennsylvania and Florida. Other key non-aligned states included Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Georgia, Delaware, Maryland, West Virginia, Kentucky, and Missouri.

Towards the end of this period, as these non-aligned states increasingly saw the need for a collective platform, the "Non-Aligned States Forum" emerged. This annual gathering of governors and key legislative leaders was not a compact itself, but a vital institution for these "balancer" states. Federal politics transformed into an intricate negotiation among these varied entities.

The Dawn of Formalized Regionalism: The Federal-Compact Recognition Act and Its Affirmation

As the 2060s dawned, the de facto power of the major Regional Compacts had become an undeniable feature of the American political system. The constant, complex negotiations required to govern pushed the federal government towards seeking a more stable and formalized relationship. This culminated in the landmark "Federal-Compact Recognition and Cooperation Act of 2062." Passed after years of contentious debate, this legislation granted formal federal recognition to "Major Interstate Regional Compacts," established frameworks for cooperation, authorized potential devolution of powers with block grants, and stipulated formal consultative roles for compacts in federal decisions impacting their regions.

The Act faced immediate legal challenges. The landmark case that settled the issue was Arizona v. Federal Inter-Compact Commission (2064). In a contentious 6-3 decision, the Supreme Court upheld the Act. The Court's majority opinion, drawing upon a broad interpretation of Article I, Section 10, Clause 3 (the Compact Clause), reasoned that the framers, while primarily envisioning simpler agreements like boundary settlements, did not intend to foreclose more ambitious forms of interstate cooperation necessary to address evolving national challenges. The Court found that the 2062 Act itself, by establishing criteria for recognition and frameworks for federal oversight, provided the requisite "Consent of Congress" for these more robust regional entities. The majority argued that the Act did not create new sovereignties or unconstitutionally delegate core federal powers, but rather acknowledged and structured a voluntary pooling of existingstate powers for more effective regional governance, a practice implicitly supported by a long history of evolving interstate compacts (citing precedents like Tri-State Water Authority v. EPA (2048) which affirmed broad state powers in forming resource management compacts). The opinion emphasized that "federalism is not a static monument but a dynamic principle, capable of adapting its forms to meet the exigent realities of a vastly more complex and regionally interdependent nation." This ruling cemented the legal standing of the major compacts as recognized entities.

Part IV: The Fracturing Era – Redrawing Internal Maps (2068-2085)

The relative stability of the mid-2060s, now underpinned by the formal recognition of major compacts, was nevertheless shattered by an abrupt "Fracturing Era" that stretched from 2068 into the mid-2080s. The "Regional Realignment Act of 2065," pushed through Congress by a coalition of now federally recognized compacts and influential non-aligned states, provided the contentious legal pathway. This Act, while nominally upholding Article IV, Section 3 of the Constitution (governing the formation of new states), introduced novel mechanisms such as formalized sub-regional referendums, defined criteria for economic viability and "irreconcilable differences," established federal mediation processes, and, crucially, gave significant weight to the endorsement of recognized Regional Compacts in Congressional consideration of new state formations.

Its passage was fiercely debated, and its constitutionality was immediately challenged. This led to the pivotal Supreme Court case of Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. Congressional Boundary Commission & The Allegheny Petitioners (2067). The "Allegheny Petitioners" represented a broad coalition from Western Pennsylvania—including county governments, local business leaders, labor unions, and civic organizations. Following a successful supermajority vote for separation in a regional referendum (as stipulated by the 2065 Act), they formally petitioned for the creation of a new state. Their central claim rested on Western Pennsylvania's distinct economic structure, heavily reliant on revived advanced manufacturing and energy resources, its unique Appalachian cultural identity, and a long history of political and economic grievances against the eastern-dominated state government. These factors, they argued, constituted "irreconcilable regional differences" that warranted separate statehood to ensure fair representation and allow the region to pursue its own development path. The rump government of Pennsylvania countered that the Regional Realignment Act itself was an unconstitutional infringement on state sovereignty, asserting that Article IV, Section 3 did not permit such a federally-influenced process to legitimize the division of an existing state against the unified will of its established government. In an extraordinarily narrow 5-4 decision, the Supreme Court upheld the core tenets of the Regional Realignment Act. The Court's majority opinion, penned by a Justice who had previously championed a dynamic view of federalism, acknowledged the profound implications of the Act for state sovereignty but ultimately found it a permissible exercise of Congressional power to manage the formation of new states and preserve the Union under extraordinary duress. The reasoning centered on the interpretation of "Consent of the Legislatures of the States concerned" in Article IV, Section 3. The Court argued that the Act did not bypass this consent but established a structured, federally supervised process by which such consent could be legitimately ascertained and expressed, particularly when internal state divisions reached a point of "irreconcilable governmental dysfunction" as demonstrated by the Act's stringent criteria (referendums, viability plans). The opinion suggested that in extreme cases, a parent state's persistent refusal to acknowledge overwhelming and democratically expressed sub-regional will for separation, after all mediation efforts under the Act were exhausted, could itself be seen as undermining the republican form of government within that sub-region. The Court stressed that Congressional approval for each new state remained the ultimate safeguard. The opinion concluded that "The Constitution provides for a 'more perfect Union,' not an immutable one. This Act, by channeling profound regional aspirations into an orderly, if arduous, legal process, offers a path away from potential chaos towards a more representative and sustainable federalism." This controversial ruling provided the legal green light for the "Fracturing Era."

The campaigns for state separation and the subsequent implementation of new boundaries were, in many instances, fraught with conflict. Nowhere was this more evident than in Pennsylvania. Following the Supreme Court's 2067 decision, the long-simmering tensions between Western Pennsylvania and the eastern-dominated state government exploded. What began as fierce urban demonstrations frequently turning violent in Pittsburgh (the heart of the secessionist movement) and Harrisburg (the state capital), alongside rival "loyalist" and "secessionist" militias engaging in localized skirmishes across the Appalachian ridges, rapidly escalated into a broader, more organized insurgency. The "Allegheny Volunteers," a well-armed secessionist militia drawing on the region's historical frontier spirit, clashed repeatedly and with increasing intensity against Pennsylvania State Police and hastily formed "Keystone Loyalist" militias determined to prevent the state's division. For nearly two years, a de facto state of low-intensity civil war gripped Pennsylvania. Key transportation corridors were disrupted, local governments in the western counties declared allegiance to a provisional Allegheny authority, and the state's economy teetered on the brink of collapse. The formal process of dividing state assets and drawing new borders became impossible amidst the escalating violence, which sparked riots and sustained acts of civil disobedience not only in the west but also in eastern cities deeply concerned about the precedent being set and the potential for wider chaos. The conflict reached a critical point where the Governor of Pennsylvania, facing a complete breakdown of public order and the inability of state forces to quell the increasingly entrenched and popularly supported Allegheny militias, formally requested federal intervention. The U.S. President, after much hesitation and under intense pressure from neighboring compacts fearing spillover of the violence, federalized the Pennsylvania National Guard and deployed elements of the U.S. Army in late 2069. Their stated mission was not to crush the secession movement itself—which the Supreme Court had deemed legally permissible under the 2065 Act—but to restore order, disarm the rival militias, and enforce a demilitarized zone while federally mediated negotiations under the Act's provisions proceeded. After months of tense standoffs, delicate diplomacy, and the establishment of interim governance structures, a separation agreement was finally brokered. Thus, after years of intense local activism, fueled by deep-seated disputes over resource allocation and divergent economic development strategies, and a bloody interlude that nearly tore the state apart, Western Pennsylvania formally separated to become the Allegheny Commonwealth in 2070, a stark and sobering example of the profound costs and complexities of regional realignment.

While other state divisions during this era were generally achieved with less sustained violence, the potential for conflict was ever-present. In non-aligned Florida, a state of vast internal diversity, the internationally-focused, densely populated southern region had long felt culturally and economically estranged from the more traditional, agriculturally-oriented northern and central parts. Decades of differing priorities on critical issues such as water management for the Everglades, strategies for coastal development in the face of rising sea levels, and international trade policies, exacerbated by the unique and severe climate change impacts battering the south, fueled a powerful secessionist movement. After a contentious campaign marked by large demonstrations and heated political maneuvering, the southern counties successfully invoked the Regional Realignment Act, forming the new state of Miami, leaving the rump "State of Florida" to govern the remaining, predominantly northern and central, territory.

Within the New England Compact, Western New York, with its economy historically more tied to the Great Lakes industrial basin and its cultural outlook often differing from the New York City-dominated downstate region, had long perceived itself as an outlier. Decades of frustration over perceived neglect from Albany regarding infrastructure investment and economic development, coupled with a desire for policies more aligned with the industrial Midwest, led to a successful separation movement. This resulted in the formation of the new state of Niagara, which promptly sought and gained admission to the Great Lakes Alliance, seeing its future more closely aligned with that regional bloc.

The Great Lakes Alliance itself was not immune to these fissiparous pressures, as internal economic and cultural fault lines became more pronounced. In Illinois, the agricultural and culturally distinct southern counties, feeling overshadowed by Chicago's immense political and economic dominance and seeking policies more attuned to their rural character and resource-based economy, successfully petitioned for separation, forming the new state of Lincoln. A similar dynamic played out in Indiana, where the southern counties, with their strong Ohio River orientation, distinct economic profile based on manufacturing and river commerce, and cultural ties to the Upland South, broke away to become the new state of Wabash. In Ohio, the southern region, centered around Cincinnati and with historical ties to river trade and Appalachian culture, also successfully utilized the 2065 Act to establish the new state of Cincinnatus, citing decades of divergent development paths from the state's northern industrial centers. The remaining northern portion of Ohio, with its strong Great Lakes identity and legacy industrial base around cities like Cleveland and Toledo, was reconstituted as the Western Reserve Commonwealth, a name evoking its historical origins.

These newly formed states, born from the fractures within larger entities, quickly sought new alignments based on shared interests and regional coherence. The Allegheny Commonwealth (from Pennsylvania), Lincoln (from Illinois), Wabash (from Indiana), and Cincinnatus (from Ohio) found immediate common cause with the long-non-aligned states of West Virginia and Kentucky. These six entities, sharing a common geography along the Ohio River, similar economic challenges related to transitioning post-industrial economies, a heritage of resource extraction, and a distinct Appalachian-influenced culture, formally established the Ohio Union. This new compact aimed to collectively address regional infrastructure needs, promote sustainable resource management, and tackle shared socio-economic concerns through coordinated policies.

Newly shorn of significant population, territory, and economic activity, the formerly powerful non-aligned "rump states" of Florida and Pennsylvania were forced to re-evaluate their positions and alliances within the rapidly changing national landscape.

Part V: The Shifting Tides – Consolidations, Secessions, and Deepening Crises (2090-2110)

The "Fracturing Era's" initial shocks gave way to a period of gradual consolidation and further, more profound, crises from the 2090s into the early 22nd century. The drive for regional coherence and the pressures of the new political landscape continued to reshape the map.

The formation of the Mid-Atlantic Compact (MAC) exemplified this trend. In New Jersey, the long-standing cultural and economic divide between its northern, New York City-orbiting counties and its southern, more Philadelphia and Delaware Valley-oriented region, reached a breaking point. Citing divergent economic needs, particularly around infrastructure investment and environmental priorities, Southern New Jersey successfully utilized the Regional Realignment Act to separate. Similarly, in Virginia, the hyper-developed, federally-connected counties of Northern Virginia felt increasingly distinct from the rest of the Commonwealth, whose economy and political focus remained more traditionally Southern. After protracted negotiations, Northern Virginia also achieved separate statehood. These two new entities, South Jersey and North Virginia, possessing strong economic ties and shared interests in managing the dense urban corridor, found natural partners in the rump "Eastern Pennsylvania" (itself a product of earlier fractures) and the historically interconnected states of Delaware and Maryland. Together, they formally chartered the Mid-Atlantic Compact, a powerful bloc focused on finance, federal relations, port activities, and the unique challenges of their densely populated region.

The fate of Missouri became a particularly complex illustration of the era's centrifugal and centripetal forces. As the eastern and central portions of the state, including St. Louis and the historic capital Jefferson City, found their economic and infrastructural interests increasingly aligned with the newly formed Ohio Union (particularly the state of Lincoln), a movement for absorption gained momentum. This process, culminating in the formal merger of these Missourian regions into an expanded state of Lincoln within the Ohio Union, was not without incident, sparking significant urban protests in the affected cities against the loss of state identity, and isolated acts of resistance from "Missouri First" groups who felt their heritage was being erased. Simultaneously, Western Missouri, with its distinct agricultural economy and closer cultural ties to the Great Plains, reacted to the turmoil by successfully petitioning for its own separation under the Regional Realignment Act. This newly formed entity, comprising the westernmost counties, was then formally admitted into the Plains Federation, effectively merging with its western neighbor, Kansas, and strengthening the Federation's presence along the Missouri River. The historic state of Missouri thus ceased to exist, its territory now divided between the expanded state of Lincoln (Ohio Union) and an enlarged Kansas (Plains Federation).

Further west, the vast, sparsely populated inland regions of the Pacific Northwest also underwent consolidation. Eastern Oregon and Eastern Washington State, having long felt culturally and economically distinct from their coastal urban centers, had successfully separated from their parent states during the earlier Fracturing Era. Now, driven by shared interests in agriculture, resource management, water rights, and a desire for a stronger collective voice within the Intermountain West, these two fledgling states negotiated a merger, forming the single new state of Columbia. This new entity was then formally welcomed into the Intermountain Pact, significantly expanding the Pact's agricultural base and strengthening its influence over the Columbia River basin. The Pacific Accord, now comprising "Coastal California," "West Washington," "West Oregon," and Hawaii, became an even more focused "Coastal Pacific States" entity, its identity sharpened by the departure of its inland territories.

This period of realignment, however, was overshadowed by events that threatened the very fabric of the remaining Union: the Great Unraveling, marked by two unprecedented secessions. Around 2106, New Mexico, an original member of the Intermountain Pact, citing deep and reasserted historical, cultural, and demographic ties to Mexico, alongside growing frustration with the perceived instability and shifting priorities of the U.S. federal system, successfully negotiated its peaceful secession from the United States to seek reincorporation into Mexico. The process, though managed without large-scale conflict, was marked by intense internal debate within New Mexico, with passionate demonstrations both for and against separation in cities like Santa Fe and Albuquerque, and the alarming, though sporadic, mobilization of private militias on both sides of the issue. Nationally, the news triggered outraged nationalist protests and scattered acts of reactionary violence in various parts of the remaining U.S., as many saw it as a betrayal and a sign of profound national weakness.

Just two years later, around 2108, inspired by New Mexico's precedent and driven by a sense of increasing geopolitical isolation, unique Arctic concerns, and perhaps seeing greater economic and strategic opportunity with its northern neighbor, Alaska also negotiated its peaceful secession from the U.S. It subsequently entered into an agreement with Canada to merge with the Yukon Territory, a move that fundamentally altered the geopolitical map of North America and control over Arctic resources. Similar to New Mexico, the period leading up to Alaska's departure involved significant internal tensions, with pro-secession/pro-Canada factions and those loyal to the U.S. engaging in heated demonstrations and some militia posturing, particularly in Anchorage and Juneau. The second secession so soon after the first amplified the nationalist backlash across the remaining U.S. states, with further instances of unrest and a palpable sense of national crisis.

The loss of two states to foreign powers, though achieved through negotiation rather than conquest, constituted an undeniable existential crisis for the United States, making fundamental constitutional reform not just desirable, but imperative for the survival of the remaining union.

Part VI: The Great Reckoning – A Reformed United States of America (2110 - 2120)

The secessions of New Mexico and Alaska served as the final, undeniable impetus for change. The atmosphere leading to the "Century 22 Appeal"—a movement culminating around 2110 calling for a new Constitutional Convention—was one of high anxiety, with some communities forming 'defense militias' and sporadic hoarding.

The Convention in Philadelphia ("Philadelphia II"), starting in 2115, was an arena of intense debate, with frequent, volatile demonstrations outside. Delegates were chosen by Regional Compacts (NEC, Coastal Pacific States, GLA, Intermountain Pact (now without NM or AK's historical claim), SSA, MAC, Ohio Union, Greater Texas, Plains Federation), the Non-Aligned States Forum, and representatives from the newly formed independent entities like the "State of Miami."

The resulting "Federal Framework of the United States of America," drafted over three years of highly concentrated effort, was presented in late 2117. The ratification process, though accelerated by preceding crises, was challenging. During these tense negotiations, the newly formed State of Miami, with its unique international character, strong independent economic base, ties to Latin America and the Caribbean, and a growing weariness of the protracted instability within the broader US, made a pivotal decision. Citing its distinct regional identity and a desire to chart its own international course unencumbered by the complexities of the reforming Union, Miami successfully negotiated its own peaceful secession to become an independent nation-state around 2119, prior to the final ratification of the Federal Framework by the remaining entities. This third secession, occurring even as a new framework was being forged, underscored the profound centrifugal forces at play and the immense difficulty of maintaining unity.

The ratification of the "Federal Framework" by the remaining entities concluded in 2120. While far from smooth, with anti-reform protests and some radical militias declaring the new system illegitimate, leading to localized standoffs, exhaustion with instability and the stark reality of further potential fragmentation ultimately carried the day.

The "Federal Framework" did not change the nation's name but fundamentally reformed its structure. The primary constituent units of this reformed United States of America were no longer the historic fifty states. Instead, the major Regional Compacts—New England Compact, Coastal Pacific States, Great Lakes Alliance, Intermountain Pact, Southern States Alliance, Mid-Atlantic Compact, Ohio Union, Greater Texas, and Plains Federation—were formally reconstituted as the new, large "States" of the Union. For example, the former New England Compact became the "State of New England"; the Great Lakes Alliance, incorporating the new state of Niagara and the rump Western Reserve Commonwealth, became the "State of the Great Lakes." The Southern States Alliance underwent a significant expansion during the negotiation of the Framework, formally integrating the remaining territories of the rump "State of Florida" (North/Central Florida), the rump "Commonwealth of Virginia," and the entirety of the formerly non-aligned states of Georgia, North Carolina, and Tennessee, forming a much larger and more cohesive regional "State" often referred to simply as "The South." Consequently, the old state boundaries, where they did not align with these new regional "States," were effectively superseded as the primary basis of federal division.

Under this new Federal Framework, most domestic policy powers were formally devolved to these new, powerful "States." The authority of the federal government was explicitly limited to crucial areas of shared national interest: common defense of the reformed USA's territory, the conduct of a unified foreign policy, the maintenance of a common currency and customs union, the protection of fundamental civil rights as enumerated in a revised Bill of Rights applicable across all new "States," the adjudication of disputes between these new "States" via a newly constituted Constitutional Court, and the coordination of inter-State infrastructure deemed of truly national significance. The governance structure featured an indirectly elected President, whose duties became largely ceremonial and focused on foreign policy, while a unicameral "Council of States"—where each new "State" had representation, possibly weighted by a combination of population and a set number of seats per entity—became the primary legislative body for federal matters. This reformed USA also established a Common Market, ensuring the freedom of movement for people, goods, and capital across all its constituent "States." Furthermore, it maintained principles of "variable geometry," allowing the new "States" to integrate more deeply on certain issues by mutual consent, and, crucially in light of the recent secessions, included clearly defined, though exceptionally stringent, processes for the potential exit of one of these new "States."

America 350

By 2120, the reformed United States of America was a functioning, if nascent, reality—a federation of powerful, largely autonomous regional States, established just six years before the nation's 350th anniversary. The Tricentennial in 2076 had passed almost entirely unobserved, lost amidst the turmoil of the "Fracturing Era."

The ratification of the "Federal Framework" in 2120 was seen by many not just as a political restructuring but as a profound moment of national rebirth. As the new "States" began to operate within this looser confederation, regional identities flourished, yet paradoxically, successfully navigating such a fundamental crisis fostered a renewed, if different, sense of overarching American cultural nationhood—a more mature, pluralistic identity.Thus, when 2126 arrived, the 350th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence took on immense significance. It became a delayed celebration of the nation's endurance and capacity for reinvention, an opportunity to acknowledge the painful journey while affirming a collective commitment to this new, reformed Union. The festivities varied greatly from one regional "State" to another, yet all occurred under the shared banner of a United States that had, against considerable odds, found a way to continue. National identity was now understood as a mosaic, with loyalty to one's regional "State" complementing a broader affiliation with the USA as a whole.

Member discussion