Generative Artificial Intelligence and Archives: Two Years On

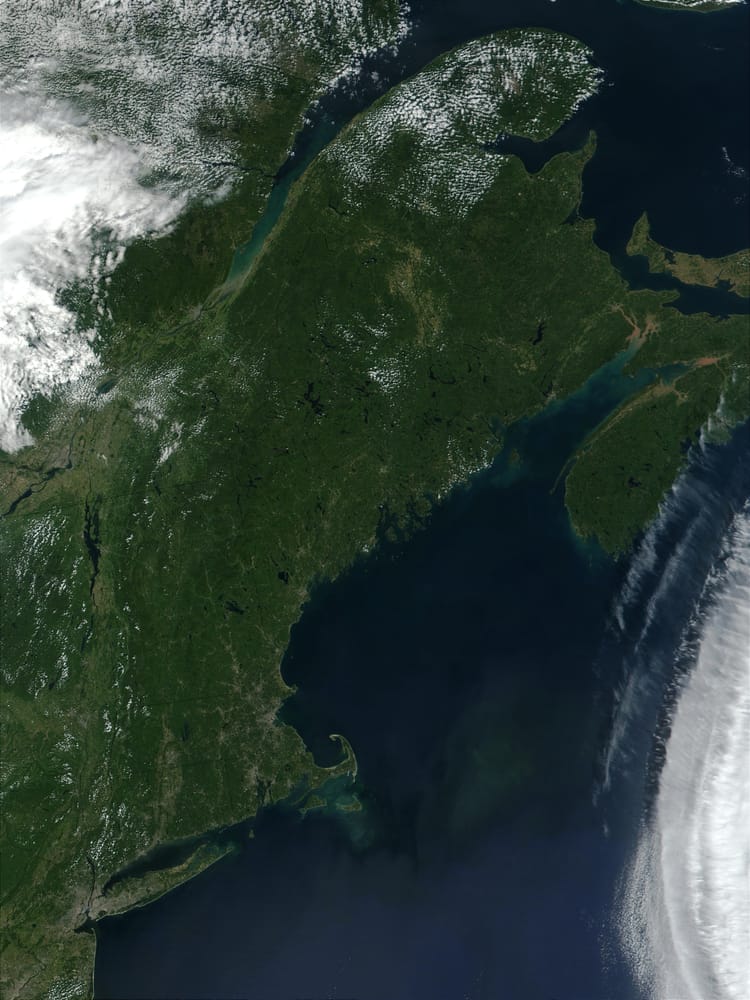

Yesterday I gave a talk on AI and archives at the Colby/Bates/Bowdoin Special Collections and Archives Staff Retreat. Thanks to the staff of the George J. Mitchell Department of Archives and Special Collections and the Bowdoin Library, the amazing Schiller Center for Coastal Studies, where the event was held, and Bowdoin's Hastings Initiative for AI and Humanity, which helped support the event. I've rarely encountered a more complete combination of scholarly engagement and hospitality. The following is a lightly edited but faithful transcript of my remarks. The reference list and reading list I provided to attendees is included at the end of the post.

Good morning. It's a pleasure to be with you here at Bowdoin. In 2023, I gave a talk at Dartmouth on a similar topic, and it's a testament to the speed of change in this field that my hosts here asked for an "updated" version. In the world of generative AI, two years is practically a lifetime. What was then a subject of speculation has by now become a pervasive force.

In that Dartmouth talk, I argued that generative AI was the biggest change in the information landscape since the advent of the web. I think that's proven correct. The pace of development has been startling, and the tools have become exponentially more powerful and accessible. We've moved beyond the initial "wow" factor and are now grappling with the complex realities of integrating these technologies into our work as archivists and historians.

AI and Archives in 2025: Promise and Peril

So, what's new? What has changed in the last two years? And how should we, as professionals dedicated to the preservation and interpretation of the past, respond?

The most significant development, I believe, has been the move from AI as a curiosity to AI as a practical tool. Consider the challenge of handwritten text. For centuries, vast collections of manuscript materials—diaries, letters, logbooks, administrative records—have been accessible only to scholars with the specific training to decipher them and the time and funding to travel to the archives where they are held. Today, we can train models on specific hands and scripts, turning once-indecipherable documents into searchable, analyzable data. Even general purpose models like ChatGPT can do a decent job at this. Likewise, AI-powered tools for automated cataloging and metadata generation promise to make our collections more discoverable. At a time when most archives are struggling with significant backlogs and limited resources, these technologies can offer a way to do more with less. These aren’t just efficiency gains; these technologies open entirely new avenues of inquiry. We can now ask questions about language, society, and culture across thousands of documents in a way that was simply impossible a decade ago.

But with this great promise comes great peril. The fundamental problems have not gone away. The issue of "hallucinations"—the tendency of these models to generate plausible-sounding but false information, complete with fake citations to real-looking articles—remains a profound challenge. For us, as historians and archivists who trade in verifiable facts, this is a crisis of epistemology. And it’s compounded by the "black box" nature of these systems. We often don't know how they arrive at their conclusions, making it impossible ever to trust them completely.

Then there is the issue of bias. Large language models are trained on vast datasets of text and images from the internet, and they inevitably reflect the biases present in that data. This means that they can perpetuate and even amplify existing inequalities and stereotypes. For those of us committed to telling more inclusive and diverse stories about the past, this is a serious problem. As we begin to use AI to generate not just text, but also images and other media, the potential for misuse and disinformation grows. Organizations such as the Archival Producers Alliance have started developing guidelines for the ethical use of AI, a welcome and necessary step in establishing ethical standards for this new creative landscape. But much more work is needed.

Beyond these technical and ethical flaws, however, lies a more unsettling, existential peril. We must confront the very real possibility that AIs will simply become better than humans at many of the core tasks of our professions. An AI can already synthesize secondary literature more broadly and quickly than any human. Soon, it may be better at identifying patterns across vast archival collections, at generating initial classifications for incoming records, and at drafting historical narratives. This poses a direct threat to our livelihoods, and brings into question our professions as viable career paths for our graduate students and early-career professionals.

But more profoundly, it strikes at the heart of our dignity and sense of purpose. If the intellectual labor we've dedicated our lives to—the stewardship of collections, the careful assessment of evidence, the construction of historical arguments—can be automated and optimized, what does that mean for human flourishing? This is the fundamental question that we—especially we humanists—must now begin to answer.

Eleven Shifts

So, where does that leave us? How do we navigate this complex and rapidly evolving terrain? In 2023, I proposed eight practical shifts for teaching and learning with primary sources in the age of AI. Today, I’d like to revisit and expand on them. In the whirlwind of the past two years, which have held up? Which seem less relevant, or have been twisted into new and more complex shapes? And what new shifts must we consider?

Let's go through them one at a time.

1. Focus on the Physical

Two years ago, I argued that since AIs are trained on digital data, the ability to work with undigitized, physical sources would become a significant "value add" for humans. Today, I believe this is more relevant than ever, and more profound than I originally imagined. In an age of infinite, frictionless, AI-generated content, the authentic, scarce, and frictional experience of the physical artifact takes on an almost spiritual significance. An AI can summarize every digitized book about the Great Depression, but it cannot replicate the experience of holding a Dust Bowl migrant's letter. That sensory, material engagement is a form of knowledge in itself, and it is a uniquely human one. This is the future of humanistic work: engaging with the stuff the AI can’t know. Our students, born into the age of Google, are often less adept at navigating physical archives. They will need to get better, and we will need to teach them.

That said, if the last two years have taught us anything, it’s that things can change fast. The physical object’s resistance to machine reading may not last forever. Advances in robotics and computer vision may one day produce AIs that can "read" physical archives. But even then, the human act of selection, interpretation, and tactile engagement will remain distinct. Our charge as educators is to teach students how to do this work, because they are a generation that has been trained to believe that if it's not online, it doesn't exist.

Moreover, we must also acknowledge the real-world constraints of travel, time, and funding. A renewed focus on the physical cannot mean a retreat into elitism, where only those with generous grants can access unique materials. This calls for new models of access that are neither mass digitization nor a plane ticket. Peer-to-peer networks that connect researchers with archivists and local proxies are one promising path. This is the idea behind Sourcery, an app that my colleagues and I have developed: to create a system where a researcher can request digital access to an undigitized item and a fellow researcher or archivist on site can provide it, reintroducing human mediation and collaboration into remote archival work.

And when we do create digital surrogates, we must do so with integrity. The answer is not a flat JPEG on a webpage, devoid of context. The answer lies in community-driven standards that embody our professional values. In this way, standards like the International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF), aren’t just technologies, they are ethical commitments. Using IIIF, an archive can serve up an image with deep zoom and structured metadata and make it interoperable with other objects from other institutions, providing the rich context that AI too often strips away. IIIF enables tools like the Mirador viewer (which allows a scholar to pull documents from disparate collections into the same browser window for side-by-side comparison) and apps like Booksnake (which uses augmented reality to allow users to explore large format archival materials in life size using an iPhone or iPad) to provide a powerful, authentic alternative to the superficial reading of an AI. These tools don't replace human expertise; they augment it.

2. Rethinking Open Access

My second point two years ago was that we should rethink our open access digitization programs. This was a provocative statement. For thirty years, the prevailing ethos in libraries and archives has been that more open is always better. But when the beneficiaries of that openness are not just scholars and the public, but multi-billion dollar corporations scraping our collections to train proprietary models for profit, we have to ask ourselves some hard questions. We built a beautiful digital commons for scholarship and public enrichment. Now it's being strip-mined. How do we protect the commons without putting a fence around it and declaring it private property?

The answer likely lies in developing new kinds of licenses and new platforms for sharing data that are built on our values, not the values of Silicon Valley. Tools like Creative Commons licenses and RightsStatements.org are a good starting point. They allow institutions to move beyond a simple open/closed binary and clearly state, in machine-readable terms, how materials can and cannot be used. These protocols promise a way we can continue to support scholarship and public access while placing clear ethical and legal barriers in the way of wholesale corporate data harvesting.

The challenge is how to enforce these barriers if AI companies refuse to recognize them or even admit when they transgress them. The outcome of the legal battles now being waged by the New York Times, the Authors’ Alliance, and other copyright holders against the AI giants will be crucial in determining whether the commons can survive.

3. Human-to-Human Connection

Third, I urged a focus on human-to-human connection. Two years ago I worried that as AI gets better at doing things online, our students, already shaped by the pandemic, would retreat further into the virtual. Sadly, to some extent, this is already happening. We now have AI tutors, AI assistants, and even AI companions. The risk is no longer just that students will use AI to do their homework; it's that they might use it to mediate their entire learning experience, substituting the algorithm's efficient response for the messy, challenging, and ultimately rewarding process of a classroom debate or a conversation during office hours or even sharing beers at party.

Liberal arts colleges like Colby, Bates, and Bowdoin offer an antidote to this grim future. The mission of these institutions has never been simply to transmit information. We are here to foster dialogue, build intellectual community, and teach students how to listen, argue, and collaborate: in other words, to do what we’re doing right here, right now. In the age of AI, the most valuable thing we offer may be the seminar table itself: the furniture for unscripted, un-optimized, and deeply human interaction. In the age of AI, protecting and championing that space is a matter of pedagogical urgency.

4. Authentic Interest

My fourth, and related, point was the need to help students cultivate authentic, personal interests. AIs are brilliant at writing "to the test." They can figure out what the teacher, the school board, or the boss wants—and deliver it perfectly.

But an AI cannot tell a student what they, themselves, genuinely find interesting. Our students live within an "algorithmic self," their tastes and preferences shaped by recommendation engines on every platform they use. AI supercharges this. It can create a personalized feedback loop so compelling that a student may never need to develop their own intrinsic motivation.

Our job, especially when teaching with primary sources, is to be agents of serendipity. It's about helping a student stumble upon that one weird, inscrutable, captivating document in the archive that doesn't fit any pattern but sparks a genuine question. That spark of authentic curiosity is something AI cannot replicate.

5. "Names and Dates" History

At Dartmouth I made the unfashionable case for returning to "names and dates history." I’ve only become more convinced. For thirty years, the conventional wisdom in history education has been that rote memorization of names and dates is unproductive. Teaching facts seemed at odds with a new focus on thematic and causal understanding, critical thinking, and connection to the student’s own lived experience.

But memorized facts are the substrate of creative insight. A historian who can hold multiple, seemingly disconnected events, names, and dates in their mind at once can perceive a harmony or a dissonance that an AI, trained on statistical correlations, will miss. It’s like a musician practicing scales. The scales themselves are not music, but fluency with them is what allows for improvisation and true artistry. The ability to make a creative leap between two disparate events you hold in your head is a form of human cognition we must continue to cultivate. That's where new historical arguments are born.

6. Reading for Immersion

Sixth, I advocated for teaching students to read for immersion, not just for analysis. This will require a wholesale overhaul of the K-12 reading curriculum.

For the last twenty years, we have trained students to read tactically—to hunt for the thesis and extract evidence. This is exactly how an AI reads. It rips through texts to extract information and answer a query. We will not be able to teach our students to do it better than the machine.

But humans can read differently. Humans can read to be moved, to be transported, to inhabit another's consciousness, to build empathy. As our students are equipped with ever-more-powerful analytical tools, we must remind them that some forms of understanding are not about finding answers, but about learning to ask better questions or simply being present with the complexity of the past. It is this imaginative and moral mode of reading that will set human cognition apart. Fostering it will create lasting personal and professional value for our students.

7. Prompting as Methodology

Seventh, I said we needed to get better at asking these models the right questions. What seemed like a practical tip in 2023 has, by 2025, become an essential digital literacy. And it’s more than a technical skill. It's more like a new kind of research methodology, one that turns the AI from an encyclopedia into a sparring partner.

Imagine a college archivist drafting a grant proposal for an innovative but logistically and pedagogically complicated program to bring Kindergarteners into the archive. A novice user of AI might ask, "How can Kindergarteners benefit from using archives?" The result will be generic.

But an experienced user would conduct a multi-step dialogue to think through the problem. They might start by saying, "Act as a archivist writing a grant proposal for their state department of education. Draft a one-page project description for a pilot program to bring Kindergarteners into the archives of a small college. Use the voice of a professional library and information sciences professional, who has a good knowledge of the early childhood education literature, and clearly outline the pedagogical needs the program would meet and the broader impacts it would have."

Then, to anticipate the review process, the archivist would prompt: "Now, act as a skeptical grant reviewer from the state department of education. Your background is in early childhood curriculum, and you have concerns about the pedagogical soundness and safety of bringing five-year-olds into a special collections environment. Write a critique focusing on these practical and pedagogical issues."

Finally, armed with this critical feedback, the archivist can create a much stronger proposal: "As the archivist, revise the original project description to proactively address the reviewer's concerns. Add specific details about hands-on activities suitable for Kindergarteners, outline the safety protocols, and connect the archival experience directly to state learning standards for early childhood education."

When used not as a search engine, but as an interlocutor, AI becomes a tool for thinking, anticipating, and strategizing.

But this kind of use requires training and practice that aren’t supported in the formal curriculum. Certainly these aren’t things that any of us learned in school. Fortunately, we already have successful models for community-based up-skilling. Organizations like The Carpentries—with their Software, Data, and Library Carpentry workshops—have proven that we can teach foundational technical skills in collaborative, peer-led environments. An AI Carpentry movement would apply that same model to the new literacies of AI, teaching a new generation of students and scholars how to work with these tools critically and effectively.

8. Citation and Ethics

Eighth, I called for establishing good citation practices. On the surface, this has been solved; the major style guides like Chicago and MLA now have standards. We know how to cite an AI.

But the deeper challenge has emerged: the ethics of when and why. Where is the line? Using AI to check your grammar is one thing. Using it to brainstorm ideas? To generate an outline? To write a first draft that you then edit? To polish your final prose?

There are no easy answers, and institutional policies are still lagging. What we must inculcate in ourselves and our students is a principle of transparency and intellectual honesty. The guiding question should be: "Is my use of this tool enhancing my own thinking, or is it replacing it?" Librarians and archivists must be leaders here, because, as Lorcan Dempsey has argued, the erosion of trust in authorship is especially problematic for collecting institutions, which are entrusted with “the curation of validated knowledge, evidence, and memories.”

In fact, it is in this spirit that I would like to disclose that I used Google’s Gemini 2.5 Pro AI at various stages in the preparation of this talk. Among other things, based on a list of sources I provided, I asked the AI what my original talk may have missed and what new directions this updated version might take. I used it to suggest additional references. I asked the AI to read a first draft as an archivist skeptical of AI and to provide critique accordingly. I held a conversation with the AI about authenticity and how that concept operated in the text. I worked with it to produce and revise images for these slides based on passages in the text. I asked it for help in proofreading. And, finally, I used it to help brainstorm a set of new shifts that weren’t in my original talk, shifts 9-11, which I’ll turn to in a moment.

I can say in complete good conscience that I am the author of this talk. At the same time it is only right that I acknowledge Gemini as a key collaborator, one with perhaps the status of a talented graduate research assistant or perhaps even a “second” or “third author” of the kind you’d have on a scientific paper. I share this not just for transparency's sake, but to demonstrate that it's possible to use these tools as genuine partners in thought, rather than as replacements for it—which is the very distinction we must teach.

9. Multimodality

When I first gave this talk, my focus was text, because that’s what ChatGPT trafficked in. Today, AI's expansion into multimodality—its ability to see, hear, and speak—represents a step change for archives. The opportunities are staggering. Imagine pointing an AI tool at the vast Farm Security Administration photograph collection and asking it to “find all images containing a hand-plow,” or “group all photographs by the type of dwelling shown,” or “display images showing a farm worker interacting with a supervisor.” This is discovery at a scale that was previously unthinkable for visual collections.

But this power forces a difficult reckoning. Put aside issues of misidentification and hallucination. The same tool that identifies a plow can be used to perform facial recognition on historical photographs of protestors, potentially identifying individuals in vulnerable situations without their consent. The same tool that transcribes an oral history can be used to analyze the vocal patterns of a trauma survivor for emotional content, a profound ethical violation. And as AI becomes adept at generating realistic historical "photographs" or audio deepfakes from these very collections, our role in authenticating the record becomes exponentially more complex.

The practical shift here is to move beyond a text-centric view of AI. In a reflection of our own interests, in many ways our conversations in the academy, especially in the humanities, are still centered around text bots. But the challenges of multimodal AI are even more profound. We must urgently develop new literacies and ethical frameworks for working with AI across the full spectrum of archival media, treating the visual and audio record with the profound care and critical rigor it demands.

10. Bespoke AI

This brings us to a crucial counter-move against the corporate enclosure I discussed earlier. If the primary threat is our dependency on a few large, commercial entities, then our most powerful act of resistance is to change the means of production. For the past two years, and even before with voice assistants like Siri and Alexa, we have interacted with AI primarily as consumers. We use massive, general-purpose models created by a handful of large corporations, sending our data to their servers and working within their terms of service. This has rightly raised concerns about privacy, corporate control, and the homogenization of knowledge. But there are alternatives: smaller, open-source models that can be "fine-tuned" for specific tasks and even run on local machines.

This presents a transformative opportunity for archives and humanities projects to become creators of AI. Instead of relying on a generic model trained on the whole internet—with all its toxicity and bias—an archive could train a specialized model exclusively on its own collections and a set of hand-picked contextual sources and provide answers to researcher questions in the style of the archive’s own cataloging voice. A new project called The Public Interest Corpus launched by the Authors Alliance and my colleague Dan Cohen, university librarian at Northeastern, is paving the way toward something along these lines in its efforts to develop a high-quality AI training dataset from and for the world’s memory organizations. These efforts are not just in the future, however. Transkribus, for example, has started offering its open source, not-for-profit transcription model as an APIs. My colleagues at Digital Scholar are exploring how to implement the Transkribus API within Tropy, our tool for organizing research images, which would allow users the ability to search the full text of handwritten documents in the photo collections they have assembled in their archival research.

This is a move toward what we might call intellectual sovereignty. It is the difference between asking a question of a global, commercial entity and asking a question of the library itself. This shift empowers us to build our own tools that reflect the unique character, values, and intellectual traditions of our institutions.

11. From Curation to Certification — Guaranteeing the Human Record

A deeply unsettling idea known as the "Dead Internet Theory" has recently gained traction among internet researchers. The theory posits that as AI generates more and more content, the internet is becoming filled with synthetic text, images, and interactions, drowning out authentic human contributions. A related concept in AI development is "model collapse," where future AI models, trained on the AI-generated content of their predecessors, enter a recursive loop of self-referential imitation. The risk is an information ecosystem that becomes a stagnant, endlessly reproducing echo chamber of content functionally created before the AI revolution—a digital world where human history, for all practical purposes, stops around 2023.

For historians and archivists, this is an existential threat. How will future generations study our era if the digital record is an indecipherable mass of synthetic content? This is where the archive's role must undergo a critical evolution. The practical shift is moving our core function from the relatively passive act of curation to the active, authoritative act of certification.

Historically, we have curated the past—selecting, preserving, and providing access to records of what has already happened. To combat a synthetic future, we must now actively work to certify the present. We can do this using the tools of our trade. Persistent Identifiers (PIDs) like ORCID IDs, DOIs, and ARKs are the technical bedrock for a stable scholarly ecosystem. They provide a verifiable and permanent link between a digital object, its creator, and its host institution—a machine-readable stamp of authenticity. Meanwhile, new efforts like the Authors’ Alliance’s “Human Authored” certification and the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity’s C2PA standard (which the Library of Congress is exploring adopting) are taking this a step further, providing tools for the active certification of human-authored content.

In this future, the archive becomes more than a repository; it becomes a guarantor. It serves as the trusted source of "clean," verified human data—the essential ground truth against which the synthetic world can be measured. The most vital function of the archivist in the 21st century may be to draw a clear line in the digital sand and authoritatively state, "This, right here, was made by a human."

Conclusion

So, where does this leave us?

These eleven shifts are not just adaptations; they are affirmations of our core mission, and they are all fundamentally about authenticity. They call us to re-engage with the authentic physical object, to ensure the authenticity of its digital surrogate, to foster authentic human connection and curiosity, and ultimately, to embrace a new role as the certifiers of the authentic human record itself.

Generative AI is not a tidal wave that will wash us away. It is a powerful new current, and we have a choice. We can be swept along by it, or we can learn to swim. Doing so will require us to be more intentional about what we do. It will demand that we get back to the fundamentals of our professions: a commitment to evidence and truth, a deep engagement with the material traces of the past, and a belief in the irreplaceable value of human connection and imagination.

This is the thread that ties my eleven shifts together. AI requires us to think deeply about and then do the things the robots cannot do. Like all the technological revolutions that came before it, the changes AI demands of us are not to become more like the machine, but to become better at being human. Better teachers, better historians, better archivists.

References

Projects & Applications

- Sourcery: A peer-to-peer network for requesting and providing access to undigitized archival materials.

- Mirador: An open-source, web-based image viewer that supports side-by-side comparison of IIIF resources from around the world.

- Booksnake: An iOS app that uses augmented reality to view IIIF-compatible archival materials in life size.

- The Carpentries: A non-profit organization that teaches foundational coding and data skills to researchers worldwide.

- Transkribus: A comprehensive platform for the digitization, AI-powered text recognition, and transcription of manuscripts.

- Tropy: A free, open-source tool to help researchers organize and describe their research photos.

- The Public Interest Corpus: An initiative from the Authors Alliance and Northeastern University to build a high-quality library-based dataset for training AI models.

Standards & Frameworks

- International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF): A community-driven set of standards for delivering high-quality image and audio/video resources online.

- Creative Commons: A suite of public copyright licenses that enable the free distribution of otherwise copyrighted work.

- RightsStatements.org: A set of standardized statements to communicate the copyright and reuse status of digital objects.

- ORCID (Open Researcher and Contributor ID): Persistent digital identifiers for researchers.

- DOI (Digital Object Identifier): Persistent identifiers for objects, such as journal articles and datasets.

- ARK (Archival Resource Key): Persistent identifiers designed for the long-term stewardship of information objects.

Organizations & Resources

- Digital Scholar: The non-profit organization that develops Tropy, Sourcery, Omeka, and Zotero.

- Archival Producers Alliance: An organization of archival researchers that has developed guidelines for AI use in documentaries.

- Authors' Alliance: A non-profit organization representing the interests of authors and creating mechanisms for authors to certify the authenticity of their creations.

- C2PA: A new standards body working to provide open technical standards for establishing the origins and edits of digital content.

Further Reading

- Baudrillard, Jean. Simulacra and Simulation. Translated by Sheila Faria Glaser, University of Michigan Press, 1994.

- Benjamin, Walter. "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction." In Illuminations: Essays and Reflections, edited by Hannah Arendt, translated by Harry Zohn, Schocken Books, 1968.

- Blevins, Cameron. "A Large Language Model Walks Into an Archive...," October 25, 2024, https://cblevins.github.io/posts/llm-primary-sources/.

- Breen, Benjamin. “AI Makes the Humanities More Important, but Also a Lot Weirder,” Res Obscura, May 7, 2025, https://resobscura.substack.com/p/ai-makes-the-humanities-more-important.

- Breen, Benjamin. “AI Legibility, Physical Archives, and the Future of Research,” Res Obscura, March 5, 2025, https://resobscura.substack.com/p/ai-legibility-archives-future-of-research.

- Breen, Benjamin. “The Leading AI Models Are Now Good Historians,” Res Obscura, January 22, 2025, https://resobscura.substack.com/p/the-leading-ai-models-are-now-very.

- Breen, Benjamin. “How to Use Generative AI for Historical Research,” Res Obscura, November 14, 2023, https://resobscura.substack.com/p/generative-ai-for-historical-research.

- Breen, Benjamin. “Simulating History with Multimodal AI: An Update,” Res Obscura, October 18, 2023, https://resobscura.substack.com/p/simulating-history-with-multimodal.

- Breen, Benjamin. “Simulating History with ChatGPT,” Res Obscura, September 12, 2023, https://resobscura.substack.com/p/simulating-history-with-chatgpt.

- Burnett, D. Graham. “Will the Humanities Survive Artificial Intelligence?,” The New Yorker, April 26, 2025, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/the-weekend-essay/will-the-humanities-survive-artificial-intelligence.

- Cohen, Dan. "Asking Good Questions Is Harder Than Giving Great Answers," March 18, 2025, https://newsletter.dancohen.org/archive/asking-good-questions-is-harder-than-giving-great-answers/.

- Cohen, Dan. "The Unresolved Tension Between AI and Learning," January 16, 2025, https://newsletter.dancohen.org/archive/the-unresolved-tension-between-ai-and-learning/.

- Coleman, Gabriella. Coding Freedom: The Ethics and Aesthetics of Hacking. Princeton University Press, 2013.

- DeLong, Brad. “From ChatGPT Back to Clay & Cuneiform: A Start at Rethinking Pedagogy for the Age of ‘AI,’” Brad DeLong’s Grasping Reality, May 31, 2025, https://braddelong.substack.com/p/from-chatgpt-back-to-clay-and-cuneiform?triedRedirect=true.

- Dempsey, Lorcan. “Generative AI and Libraries: Seven Contexts,” LorcanDempsey.Net, November 12, 2023, https://www.lorcandempsey.net/generative-ai-and-libraries-7-contexts/.

- Drucker, Johanna. Graphesis: Visual Forms of Knowledge Production. Harvard University Press, 2014.

- Gaddis, John Lewis. The Landscape of History: How Historians Map the Past. Oxford University Press, 2002.

- Anthony Grafton, The Footnote: A Curious History. Harvard University Press, 1997.

- Kirschenbaum, Matthew G. Mechanisms: New Media and the Forensic Imagination. MIT Press, 2008.

- Matthews, Brian. Academic Libraries as Arbiters of Truth in the Age of AI, April, 23. 2025. https://www.brianmathews.io/blog/7-ways-academic-libraries-can-become-arbiters-of-truth-in-the-age-of-ai.

- Meadows, R. Darrell and Joshua Sternfeld, “Artificial Intelligence and the Practice of History,” The American Historical Review 128, no. 3 (2023): 1345–49, https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/rhad362.

- Mitchell, W. J. T. What Do Pictures Want? The Lives and Loves of Images. University of Chicago Press, 2005.

- Mollick, Ethan. Co-Intelligence: Living and Working with AI. Portfolio, 2024.

- Mollick, Ethan."The End of Search, The Beginning of Research," February 3, 2025, https://www.oneusefulthing.org/p/the-end-of-search-the-beginning-of.

- Mollick, Ethan. "Prophecies of the Flood," January 10, 2025, https://www.oneusefulthing.org/p/prophecies-of-the-flood.

- Mollick, Ethan. "Post-Apocalyptic Education," August 30, 2024, https://www.oneusefulthing.org/p/post-apocalyptic-education.

- Mollick, Ethan. "The Homework Apocalypse," July 1, 2023, https://www.oneusefulthing.org/p/the-homework-apocalypse.

- Niemann, Christopher. “Sketched Out: An Illustrator Confronts His Fears About A.I. Art,” Magazine, The New York Times, June 23, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2025/06/23/magazine/ai-art-artists-illustrator.html.

- Pariser, Eli. The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding from You. Penguin, 2011.

- Reich, Justin. Failure to Disrupt: Why Technology Alone Can’t Transform Education. Harvard University Press, 2020.

- Srnicek, Nick. Platform Capitalism. Polity Press, 2016.

- Torralba, Antonio, Phillip Isola, and William T. Freeman. Foundations of Computer Vision. The MIT Press, 2024.

- Turkle, Sherry. Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other. Basic Books, 2011.

- Wasik, Bill. “A.I. Is Poised to Rewrite History. Literally.,” Magazine, The New York Times, June 16, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/06/16/magazine/ai-history-historians-scholarship.html.

- Wolf, Maryanne. Reader, Come Home: The Reading Brain in a Digital World. Harper, 2018.

- Zuboff, Shoshana. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. PublicAffairs, 2019.

Member discussion